News

BIO Virtual Workshop: BIO’s Coaches Answer First-Time Biographers’ Questions about Proposal Writing and Promotion

Three accomplished biographers who have worked with other writers to help bring their biographies to life answered questions about proposal writing and promotion. You see the video here.

Three accomplished biographers who have worked with other writers to help bring their biographies to life answered questions about proposal writing and promotion. You see the video here.

Moderator: Marlene Trestman is the author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin, and is now writing Most Fortunate Unfortunates: New Orleans’s Jewish Orphans’ Home, 1855-1946 for LSU Press. The former Special Assistant to Maryland’s Attorney General, Trestman enforced consumer and public health laws, twice earning Exceptional Service awards. For her writing, Trestman has received funding from NEH, Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Supreme Court Historical Society, American Jewish Archives, and Texas Jewish Historical Society.

Panel: Gretchen H. Gerzina is the Paul Murray Kendall Professor of Biography at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Previously she was the Kathe Tappe Vernon Professor in Biography at Dartmouth College. She has published nine books, four of them biographies of people who crossed lines of geography, culture, and/or race. She has held grants or fellowships from NEH, Fulbright, and Oxford University, and has twice served on the jury for the Pulitzer Prize in biography, once as chair. She is currently working on two new books.

Carla Kaplan, Davis Distinguished Professor of American Literature at Northeastern University and Founding Director of its Humanities Center, has received fellowships from the NEH, Guggenheim Foundation, Schomburg Center, and elsewhere, and has published seven books, including Miss Anne in Harlem: The White Women of the Black Renaissance and Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (Doubleday, 2002), both New York Times Notable Books. Her current project, forthcoming from HarperCollins, is a biography of Jessica Mitford.

Anne Boyd Rioux is a member of BIO’s Board of Directors. Her books include the biography Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist (Norton, 2016). She is a two-time recipient of the NEH Public Scholar Award, currently working on a biographical narrative of the American writer Kay Boyle.

BIO Honors Gayatri Patnaik

On November 9, BIO hosted a virtual event honoring Gayatri Patnaik, winner of the 2020 Editorial Excellence Award. Taking part were three of her authors: Imani Perry, Marcus Rediker, and Jeanne Theoharis, along with literary agent Tanya McKinnon. You can see a video of the event here.

On November 9, BIO hosted a virtual event honoring Gayatri Patnaik, winner of the 2020 Editorial Excellence Award. Taking part were three of her authors: Imani Perry, Marcus Rediker, and Jeanne Theoharis, along with literary agent Tanya McKinnon. You can see a video of the event here.

Patnaik is Associate Director and Editorial Director of Beacon Press, where for 18 years she has edited and published many books on race, ethnicity, and immigration. A native of India who emigrated with her family to the United States as a child, she has focused on African American history, creating Beacon’s “ReVisioning American History” series and its “Queer Action / Queer Ideas” series.

Kai Bird, chair of BIO’s Award Committee, with Tim Duggan, Peniel Joseph, Kitty Kelley, and Megan Marshall, praised Patnaik for her work as “a very gutsy, courageous editor who has taken on some high-risk, controversial biographies and published so many outstanding authors.”

Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, is the author of Looking for Lorraine: The Radical Life of Lorraine Hansbury, winner of the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, the Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ Nonfiction, and other awards.

Marcus Rediker, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh, is the award-winning author of numerous books including The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf who became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist.

Jeanne Theoharis, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, is the author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, winner of the NAACP Image Award and the Letitia Woods Brown Award of the Association of Black Women Historians.

Tanya McKinnon, founder and principal of McKinnon Literary, represents New York Times bestselling and award-winning nonfiction that amplifies progressive voices, as well as fiction, children’s books, and graphic novels.

BIO’s Editorial Excellence Award is presented annually to an outstanding editor from nominations submitted by BIO members. Past recipients are Tim Duggan, Robert Gottlieb, Jonathan Segal, Ileene Smith, Nan A. Talese, and Robert Weil.

Gayatri Patnaik to Receive Editorial Excellence Award

At Beacon Press, Gayatri Patnaik co-edited The King Legacy series, a partnership between Beacon and Martin Luther King Jr.’s estate.

Gayatri Patnaik will receive BIO’s 2020 Editorial Excellence Award on Monday evening, November 9, at an online event featuring three of her authors: Imani Perry, Marcus Rediker, and Jeanne Theoharis, along with literary agent Tanya McKinnon.

Patnaik is Associate Director and Editorial Director of Beacon Press, where for 18 years she has edited and published many books on race, ethnicity, and immigration. A native of India who emigrated with her family to the United States as a child, she has focused on African American history, creating Beacon’s “ReVisioning American History” series and its “Queer Action / Queer Ideas” series.

Kai Bird, chair of BIO’s Award Committee, with Tim Duggan, Peniel Joseph, Kitty Kelley, and Megan Marshall, praised Patnaik for her work as “a very gutsy, courageous editor who has taken on some high-risk, controversial biographies and published so many outstanding authors.”

Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, is the author of Looking for Lorraine: The Radical Life of Lorraine Hansbury, winner of the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, the Lambda Literary Award for LGBTQ Nonfiction, and other awards.

Marcus Rediker, Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh, is the award-winning author of numerous books including The Fearless Benjamin Lay: The Quaker Dwarf who became the First Revolutionary Abolitionist.

Jeanne Theoharis, Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, is the author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, winner of the NAACP Image Award and the Letitia Woods Brown Award of the Association of Black Women Historians.

Tanya McKinnon, founder and principal of McKinnon Literary, represents New York Times bestselling and award-winning nonfiction that amplifies progressive voices, as well as fiction, children’s books, and graphic novels.

BIO’s Editorial Excellence Award is presented annually to an outstanding editor from nominations submitted by BIO members. Past recipients are Tim Duggan, Robert Gottlieb, Jonathan Segal, Ileene Smith, Nan A. Talese, and Robert Weil.

Register for free tickets on Eventbrite and receive a link to join the event on Zoom on Monday, November 9, at 7 p.m. ET.

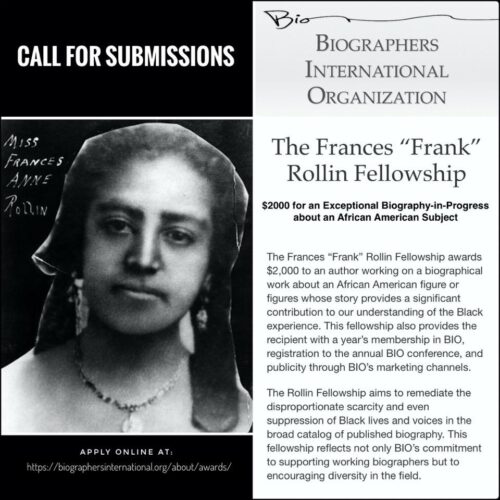

BIO Announces New Fellowship in Support of African American Lives

Frances Rollin kept one of the earliest known diaries written by a southern Black woman. Her 1868 diary covers the publication of her biography of Martin R. Delany; a transcript of it is available online through the Smithsonian Institution. Click the image to go to the diary.

By Eric K. Washington, with Sarah Kilborne, Anne Boyd Rioux, and Sonja Williams

BIO is pleased to announce the new Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship for African American Biography. The Rollin Fellowship will award $2,000 to an author working on a biographical work about an African American figure (or figures) whose story provides a significant contribution to our understanding of the Black experience. The deadline for applications is February 1, 2021.

The Rollin Fellowship is named for the first known African American biographer—Frances “Frank” Rollin—and aims to remediate the disproportionate scarcity and even suppression of Black lives and voices in the broad catalog of published biography. At its September meeting, the Board of Directors unanimously approved the new fellowship, which reinforces BIO’s mission to encourage diversity in the field.

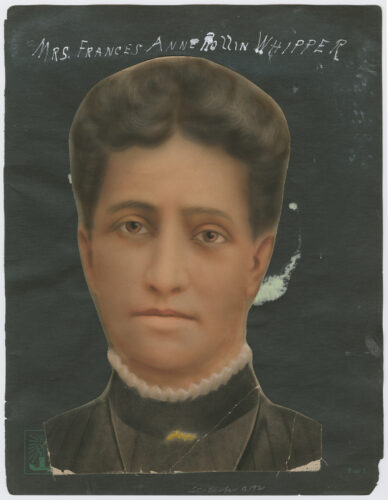

The fellowship’s namesake, Frances Anne Rollin Whipper (1845–1901)—who published as “Frank A. Rollin”—was a 19th-century author and activist. Her groundbreaking 1868 biography, Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany, presented the life of a Black abolitionist journalist, physician, and Union Army officer. The Black press recognized the significance of the precedent Rollin set and called for more biographies of African Americans. This fellowship seeks to carry forth that call into the 21st century.

The Rollin Fellowship aims to foster the development of biographical works that encourage deeper insight into the complexity of race relations at the bedrock of American history. This fellowship will support any biography that highlights the Black experience in the Americas, and that is set within the vast time period between (and even before) 1619 and the present. It will support any aspect of African American inhabitancy, dispersion, immigration, or emigration. It will support biographies of Black lives often marginalized by gender, gender-orientation, sexuality, or disability.

Please spread the word about the Rollin Fellowship through your networks. For more information, please visit the Rollin Fellowship page on BIO’s website.

Eric K. Washington chairs BIO’s ad hoc Black Lives Matter Committee, on which Anne Boyd Rioux, Sarah Kilborne, and Sonja Williams also serve.

On Being “Frank”

By Eric K. Washington

Carole Ione’s work includes the opera The Nubian Word for Flowers, a co-creation with Pauline Oliveros that debuted in 2017.

One could say Carole Ione, also known professionally as IONE—a playwright, poet, diarist, and frequent co-creator with her longtime spouse, the late composer Pauline Oliveros —has grown accustomed to long waits. As chair of BIO’s Black Lives Matter Committee, I recently had the privilege of informing Ione that Frances Anne Rollin Whipper (1845–1901) would be the namesake of a new $2,000 fellowship next spring, to be offered for a biography-in-progress of an African American figure. Whipper claimed the distinction of being the first known African American biographer in 1868, when just before her marriage she published—under the pen name “Frank A. Rollin”—Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany, about a Black abolitionist journalist, physician, and Union Army officer.

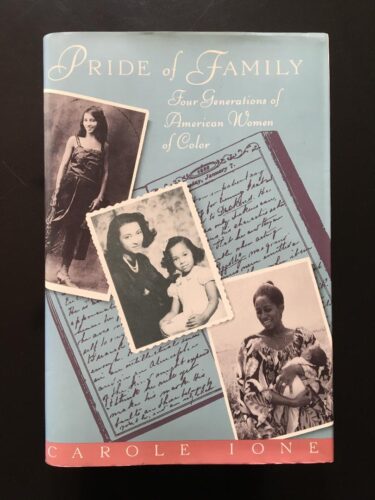

Ione had played a key role in reviving her predecessor’s nearly forgotten merit. In 1991, 90 years after Whipper’s death, Ione traversed uncharted bloodlines to an unknown great-grandmother—her book, Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, was at once biography and memoir. (The book was edited by Ileene Smith, winner of BIO’s 2019 Editorial Excellence Award.) Ione’s personally, long-awaited book received good reviews, yet nevertheless seemed ill-timed, for her publisher (Summit Books) went out of business right after its release. But nearly three decades later, Carole Ione appears no less heartened for good news.

Carole Ione’s Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color was a New York Times Notable Book.

Eric K. Washington: What was your thought when you heard your great-grandmother, Frances Rollin, was to be the namesake of a biography fellowship?

Carole Ione: Oh, it really was like a dream coming true through centuries. When I was working on my book I was obsessed with her. There’s this line in her diary in which she said she wanted to “make her mark in literature,” but many things prevented that from happening fully. She was acclaimed for the book when it came out, and then she had much other writing that was interrupted by the difficulties of the Reconstruction Congress. Her political activism remained intact, and she gave her all [to] raising kids in Washington. Yet I’ve always felt the sort of longing in her remark. And when I heard the news, I felt that it had happened.

EKW: Frances Rollin was a remarkable woman, with whom you had much in common as a writer and a diarist. Yet somehow you didn’t become acquainted with her until adulthood?

CI: Yes, my mother had mentioned that there was someone, but it was very vague. I was a freelance writer in the 70s, scrambling for all kinds of stories. Ms. magazine was happening, and I remembered something about the women in my family . . . something about a diary. My mother had sent the diary to Dorothy Sterling [another writer, then working on We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century, W. W. Norton, 1984], who sent me the diary.

So I discovered my great-grandmother [Frances Rollin, who married lawyer William J. Whipper] as an adult with children. I had a good education, but there were no African American studies at the time. When I opened the book, I said “how could I have not known about this woman my whole life?” So part of my research was in finding out, you know, why the women in my family were not forthcoming about their own lives.

The men in the family were quite renowned in their way—William S. Whipper [noted abolitionist, not to be confused with Frances’s husband, William J. Whipper], and my grandfather, Leigh Whipper [Frances’s son, the legendary stage and screen actor] . . . but when I tried to find out about the women, [the family] had very little to say. So as I began to write I looked toward this woman, Frances Anne Rollin, as the mother who would share with me all of her secrets and her needs.

EKW: Did the nonfiction genres of biography or memoir particularly interest you prior to learning of your great-grandmother’s contribution to the field?

CI: Well, I was always interested in personal writing and personal life stories. Colette, for example, was my muse from early childhood, because my mother had a book of hers, and what mother had on her shelf I gobbled up. They were not African American stories, but they were biographies. So, yes, I was very interested.

EKW: Tell us about Frances’s nom de plume, “Frank.” Literary history abounds with instances of women writers masking their gender behind male pen names. Was this her story?

CI: You know, when I was discovering her, I was involved with the early feminist movement in a very deep way. I really was incensed that she had to publish under a man’s name. But as I deepened into my research, I found evidence that the family called her “Frank,” her nickname. Frank A. Rollin was a part of who she really was. I was relieved to find that out, and from then on, she became Frank to me, and I always wrote about her in that way.

EKW: What do you see as the lasting legacy of a 19th-century Black woman first-time biographer on a generation of 21st-century biographers?

CI: I think her perseverance in writing about a very important subject—there have been other biographies of Martin Delany, but her book is the primary source of information. And the concept of her money drying up, which happens to so many writers, then persevering through the harsh times of the political climate. Also, I think her position . . .

[Here Ione evokes her great-grandmother’s rectitude by citing a diary entry on George Washington’s birthday in 1868.]

If things continue as they are, there will be but little country to celebrate it. For myself I am no enthusiast over patriotic celebrations as I am counted out of the body politic.

CI: “Frank” was acutely aware of the worldly events around her, and of taking a stand toward better elements of life for writers and for people of color and for women.

It seems that what Ione once felt to be her great-grandmother’s unfulfilled longing to “make her mark in literature” might now be a source of inspiration. She’s thrilled by the news that next year some writer will receive BIO’s first Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship. “It happened!” she exclaims, conveying a sense that her patience, over a century and a half in the making, has been well rewarded.

Eric K. Washington is a BIO board member and chair of the Black Lives Matter Committee. The New York Academy of History recently awarded his biography, Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal, its Herbert H. Lehman Prize for Distinguished Scholarship in New York History.

Biographies Live on Despite COVID

COVID-19 has upset publishers’ schedules for releasing new books, which might explain the large number of notable biographies coming out in the last few months of 2020 (some were postponed from spring releases). Traditional cradle-to-grave works, group biographies, and books about “hidden figures” are among the books generating interest among media outlets, before their fall and winter publication. We’re highlighting here just some of the books likely to garner critical and popular attention, because of their subject, their author, or both. The titles already getting buzz are drawn from Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, Booklist, Library Journal, Publishers Marketplace, and Amazon, among other sources. You can see a longer list of the season’s highly anticipated biographies on the BIO website.

Please note: TBC does its best to learn about new books and our ongoing monthly “In Stores” feature includes even more fall and winter releases. But, if we’ve missed any members’ forthcoming books, please let us know so we can add them to the list on the website. Also, keep in mind that publishing dates change, especially during the pandemic, so some books may come out earlier or later than the dates indicated.

Political Figures

As is often the case, some of the most anticipated titles focus on political figures, past and current, from around the world. September sees the release of the second book of Volker Ullrich’s two-volume study of Adolf Hitler, Hitler: Downfall: 1939–1945. Other books out this month about World War II-era figures includes The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War by Catherine Grace Katz and Agent Sonya: Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy by Ben Macintyre.

As is often the case, some of the most anticipated titles focus on political figures, past and current, from around the world. September sees the release of the second book of Volker Ullrich’s two-volume study of Adolf Hitler, Hitler: Downfall: 1939–1945. Other books out this month about World War II-era figures includes The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War by Catherine Grace Katz and Agent Sonya: Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy by Ben Macintyre.

Moving into the postwar era, out in September are JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917–1956 by Fredrik Logevall; The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War—A Tragedy in Three Acts by Scott Anderson; His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life by Jonathan Alter; Ten Days in Harlem: Fidel Castro and the Making of the 1960s by Simon Hall; The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne and Tamara Payne; and The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser. Two books about contemporary political figures are Reclaiming Her Time: The Power of Maxine Waters by Helena Andrews-Dyer and R. Eric Thomas and Blood and Oil: Mohammed bin Salman’s Ruthless Quest for Global Power by Justin Scheck and Bradley Hope.

Stepping back to figures from the 18th and 19th centuries, September’s biographies include The Virginia Dynasty: Four Presidents and the Creation of the American Nation by Lynne Cheney; Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation by Peter Cozzens; and, adding to the 16,000 or so biographies on the 16th U.S. president, Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times by David S. Reynolds.

In October, the biographies of political figures range from ancient times to today: Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors by Adrian Goldsworthy; The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom by H. W. Brands; Eleanor by David Michaelis; Stalin: Passage to Revolution by Ronald Grigor Suny; The Good American: The Epic Life of Bob Gersony, the U.S. Government’s Greatest Humanitarian by Robert D. Kaplan; and Catching the Wind: Edward Kennedy and the Liberal Hour, 1932–1975 by Neal Gabler.

Jumping to December, two books look at influential women in politics and government: Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel by Rachel Holmes and Lady Bird Johnson: Hiding in Plain Sight by Julia Sweig. In January, Alison Weir’s Queens of the Crusades: England’s Medieval Queens looks at the first five Plantagenet queens. Finally, February releases take us back to World War II and the stories of some lesser-known women: Three Ordinary Girls: The Remarkable Story of Hannie Schaft and the Oversteegen Sisters, Teenaged Saboteurs and Nazi Assassins by Tim Brady and The Princess Spy: The True Story of World War II Spy Aline Griffith, Countess of Romanones by Larry Loftis.

Literary Figures and Fine Artists

Writers of all stripes are featured in many of the forthcoming biographies. Out in September are two books about women known for their feminist works: Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir by Judith G. Coffin and Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary by Martin Duberman. October sees the release of Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark. Out in November are books about an American historian—The Last American Aristocrat: The Brilliant Life and Improbable Education of Henry Adams by David S. Brown—and an American poet, The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography by Hilary Holladay. Also out that month is a book about literary lovers, not practitioners: The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui. December’s releases include Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy by Leslie Brody, while out in January will be Ida B. the Queen: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells by Michelle Duster and The Unquiet Englishman: A Life of Graham Greene by Richard Greene. In February, a major work about a literary figure will be released: The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Author of The Yearling by Ann McCutchan.

Writers of all stripes are featured in many of the forthcoming biographies. Out in September are two books about women known for their feminist works: Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir by Judith G. Coffin and Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary by Martin Duberman. October sees the release of Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark. Out in November are books about an American historian—The Last American Aristocrat: The Brilliant Life and Improbable Education of Henry Adams by David S. Brown—and an American poet, The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography by Hilary Holladay. Also out that month is a book about literary lovers, not practitioners: The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui. December’s releases include Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy by Leslie Brody, while out in January will be Ida B. the Queen: The Extraordinary Life and Legacy of Ida B. Wells by Michelle Duster and The Unquiet Englishman: A Life of Graham Greene by Richard Greene. In February, a major work about a literary figure will be released: The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Author of The Yearling by Ann McCutchan.

Moving to the visual arts, books about two Old Masters are out in September: Goya: A Portrait of the Artist by Janis Tomlinson and Young Rembrandt by Onno Blom. A notable October release is What Becomes a Legend Most: The Biography of Richard Avedon by Philip Gefter. Three modern painters are the subjects of biographies out in November: Magritte: A Life by Alexander Danchev and Sarah Whitfield; The Lives of Lucian Freud: Fame, 1968–2011 by William Feaver; and Francis Bacon: Revelations by Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan. The latter two authors won a Pulitzer Prize for their 2005 biography of Willem de Kooning.

One notable book about a key figure from the world of classical music is Mozart: The Reign of Love by Jan Swafford, which will be out in December.

In September, rock music biographer Philip Norman takes a look at one of the most influential musicians of his generation in Wild Thing: The Short, Spellbinding Life of Jimi Hendrix. Also out this month is Three-Ring Circus: Kobe, Shaq, Phil, and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty by Jeff Pearlman—the only sports book singled out in this season’s preview. After turning his gaze on Princess Margaret, Craig Brown turns to the Fab Four with his October release, 150 Glimpses of the Beatles. Also out that month is The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall and a book about another important musician, Woody Guthrie: An Intimate Life by Gustavus Stadler. Turning to film, two books due in October are Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise by Scott Eyman and The Nolan Variations: The Movies, Mysteries, and Marvels of Christopher Nolan by Tom Shone. Fashion icon Coco Chanel is the subject of a November title, Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto by Miren Arzalluz. Out in February will be Mike Nichols: A Life by Mark Harris.Other Notable Biographies

In September, rock music biographer Philip Norman takes a look at one of the most influential musicians of his generation in Wild Thing: The Short, Spellbinding Life of Jimi Hendrix. Also out this month is Three-Ring Circus: Kobe, Shaq, Phil, and the Crazy Years of the Lakers Dynasty by Jeff Pearlman—the only sports book singled out in this season’s preview. After turning his gaze on Princess Margaret, Craig Brown turns to the Fab Four with his October release, 150 Glimpses of the Beatles. Also out that month is The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard by John Birdsall and a book about another important musician, Woody Guthrie: An Intimate Life by Gustavus Stadler. Turning to film, two books due in October are Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise by Scott Eyman and The Nolan Variations: The Movies, Mysteries, and Marvels of Christopher Nolan by Tom Shone. Fashion icon Coco Chanel is the subject of a November title, Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto by Miren Arzalluz. Out in February will be Mike Nichols: A Life by Mark Harris.Other Notable BiographiesNot all the new releases drawing attention fit into the above categories. Among them are: The Great Inoculator: The Untold Story of Daniel Sutton and His Medical Revolution by Gavin Weightman and The Martyrdom of Collins Catch the Bear by Gary Spence, both out in September; the December release El Chapo: The Untold Story of the World’s Most Infamous Drug Lord by Noah Hurowitz; and A Shot in the Moonlight: How a Freed Slave and a Confederate Soldier Fought for Justice in the Jim Crow South by Ben Montgomery, which is scheduled for a January release.Biographies by BIO Members

As is often true, the works of BIO members are well represented on the lists of forthcoming books. Out in September are Charmian Kittredge London: Trailblazer, Author, Adventurer by Iris Jamahl Dunkle; The Life of William Faulkner: This Alarming Paradox, 1935–1962 by Carl Rollyson; and Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900 by Katherine Manthorne. In October, William Souder presents a new look at a major American literary figure in Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck. Katherine Manthorne has a second book out this season, Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex, hitting the shelves in December. Also out that month is Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell by Alison M. Parker. January’s new biographies include The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine by Janice P. Nimura. Finally, February sees the publication of three books by members: Tom Stoppard: A Life by 2020 BIO Award-winner Hermione Lee; George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father by David O. Stewart; and Michael Shnayerson’s Bugsy Siegel: The Dark Side of the American Dream, part of the Yale University Press Jewish Lives series.

As is often true, the works of BIO members are well represented on the lists of forthcoming books. Out in September are Charmian Kittredge London: Trailblazer, Author, Adventurer by Iris Jamahl Dunkle; The Life of William Faulkner: This Alarming Paradox, 1935–1962 by Carl Rollyson; and Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850–1900 by Katherine Manthorne. In October, William Souder presents a new look at a major American literary figure in Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck. Katherine Manthorne has a second book out this season, Restless Enterprise: The Art and Life of Eliza Pratt Greatorex, hitting the shelves in December. Also out that month is Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell by Alison M. Parker. January’s new biographies include The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine by Janice P. Nimura. Finally, February sees the publication of three books by members: Tom Stoppard: A Life by 2020 BIO Award-winner Hermione Lee; George Washington: The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father by David O. Stewart; and Michael Shnayerson’s Bugsy Siegel: The Dark Side of the American Dream, part of the Yale University Press Jewish Lives series.

Fair Use: Q&A with the Experts

On June 9, Brandon Butler and Peter Jaszi took part in a virtual workshop for BIO on fair use for biographers. Here, Butler and Jaszi answer two follow-up questions on the topic. You can see a recording of the workshop here, and read BIO’s Statement on Best Practices regarding fair use here.

On June 9, Brandon Butler and Peter Jaszi took part in a virtual workshop for BIO on fair use for biographers. Here, Butler and Jaszi answer two follow-up questions on the topic. You can see a recording of the workshop here, and read BIO’s Statement on Best Practices regarding fair use here.

Q: Taking into account fair use doctrine, when do we—and when don’t we—have to pay licensing fees in order to use photographs and other illustrations still under copyright in our books? And how do we find out if a photograph or illustration is out of copyright and can be reprinted freely?

A: There are two key contexts in which you don’t have to pay fees to use third-party content (such as photographs or illustrative material). The first is when your use is a fair use. We covered the broad contours of the fair use doctrine, and how it applies to some recurring biographical uses, in some detail during our webinar. Another very useful source of guidance on the scope of fair use is the growing body of best practices documents developed by communities of creators and other frequent users of in-copyright works. If your use is a fair use, you don’t have to get permission or pay licensing fees. An excellent case in point, which we described during the webinar, is the Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley case. Among other useful things, the Second Circuit’s opinion informs us that:

Preliminarily, we recognize, as the district court did, that Illustrated Trip is a biographical work documenting the 30–year history of the Grateful Dead. While there are no categories of presumptively fair use, courts have frequently afforded fair use protection to the use of copyrighted material in biographies, recognizing such works as forms of historic scholarship, criticism, and comment that require incorporation of original source material for optimum treatment of their subjects.

This important case also makes clear that fair uses don’t necessarily involve critique or commentary on the work that is being used. In that case, as in many others, the point of the reproduction was to illustrate the author’s narrative—which can be an entirely legitimate fair use purpose.

The other major context for unlicensed use is when the work you’re using is in the public domain, i.e., the work is no longer protected by copyright (or, in the case of some federal government works, it never was protected by copyright). The best quick reference for determining whether a work is in the public domain is the Cornell University Library’s handy chart. And sometimes, of course, text or images you want to use are available under a general Creative Commons license.

Q: How can we talk to our editors and publishers about a more liberal interpretation of fair use, especially in light of what you told us in the Zoom workshop about courts’ evolving and more expansive views on the law over the last 20 years?

A: Most editors and publishers need to understand four key things:

- Fair use law has changed very substantially over the last two decades, including (crucially) its treatment of unpublished material. The very bad cases regarding unpublished material in biographies that were decided in the 1980s and early 1990s were overturned by an act of Congress, which added language to the Copyright Act explicitly stating that unpublished material shall be susceptible to the same balanced analysis as published materials. More generally, the law of fair use has become much, much more coherent and much more strongly favorable toward legitimate users than it was in the 1970s and 1980s.

- This change is now very, very well established. Scholars have shown, repeatedly, that if your use is “transformative,” you will win in court. Cases about biography and related scholarly uses, in particular, show a very clear mode of analysis that any author and publisher can apply favorably to their own typical, recurring uses. Plaintiffs now understand this, and they are wary of bringing lawsuits they know will lose. Courts have become quite willing to dismiss cases at early stages when a strong fair use case is evident on the face of the complaint.

- Fair use makes books better. Arbitrary omissions and alterations that are rooted in legal fear, rather than in the author’s (and the editor’s) judgment about what best serves the story, will always make a book worse. They will lead you to leave out important context, to make assertions without important evidence, to ask the reader to trust you rather than give them the opportunity to believe their own eyes. The publisher that is willing to flex their fair use rights in support of authors will publish more, better books, and they will attract authors who value the freedom to tell their stories to the fullest extent allowed by their First Amendment rights, rather than having to trim their sails in deference to illusory legal risk. For a while, this will give savvy publishers a competitive advantage.

- According to Congress, fair use is a right, and the Supreme Court has weighed in to say that it’s closely related to the First Amendment freedom of expression. So, there is nothing sneaky or disreputable about exercising the fair use right where it applies.