BIO Virtual Workshop: BIO’s Coaches Answer First-Time Biographers’ Questions about Proposal Writing and Promotion

Three accomplished biographers who have worked with other writers to help bring their biographies to life answered questions about proposal writing and promotion. You see the video here.

Three accomplished biographers who have worked with other writers to help bring their biographies to life answered questions about proposal writing and promotion. You see the video here.

Moderator: Marlene Trestman is the author of Fair Labor Lawyer: The Remarkable Life of New Deal Attorney and Supreme Court Advocate Bessie Margolin, and is now writing Most Fortunate Unfortunates: New Orleans’s Jewish Orphans’ Home, 1855-1946 for LSU Press. The former Special Assistant to Maryland’s Attorney General, Trestman enforced consumer and public health laws, twice earning Exceptional Service awards. For her writing, Trestman has received funding from NEH, Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Supreme Court Historical Society, American Jewish Archives, and Texas Jewish Historical Society.

Panel: Gretchen H. Gerzina is the Paul Murray Kendall Professor of Biography at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Previously she was the Kathe Tappe Vernon Professor in Biography at Dartmouth College. She has published nine books, four of them biographies of people who crossed lines of geography, culture, and/or race. She has held grants or fellowships from NEH, Fulbright, and Oxford University, and has twice served on the jury for the Pulitzer Prize in biography, once as chair. She is currently working on two new books.

Carla Kaplan, Davis Distinguished Professor of American Literature at Northeastern University and Founding Director of its Humanities Center, has received fellowships from the NEH, Guggenheim Foundation, Schomburg Center, and elsewhere, and has published seven books, including Miss Anne in Harlem: The White Women of the Black Renaissance and Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (Doubleday, 2002), both New York Times Notable Books. Her current project, forthcoming from HarperCollins, is a biography of Jessica Mitford.

Anne Boyd Rioux is a member of BIO’s Board of Directors. Her books include the biography Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist (Norton, 2016). She is a two-time recipient of the NEH Public Scholar Award, currently working on a biographical narrative of the American writer Kay Boyle.

On June 9, Brandon Butler and Peter Jaszi took part in a virtual workshop for BIO on fair use for biographers. Here, Butler and Jaszi answer two follow-up questions on the topic. You can see a recording of the workshop

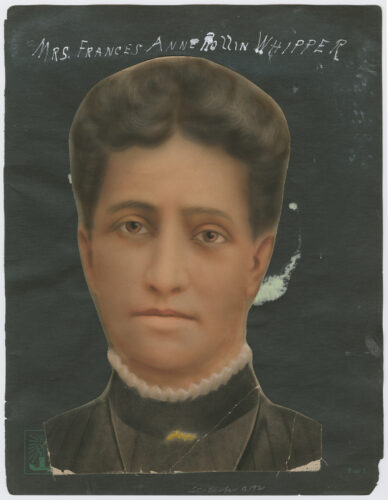

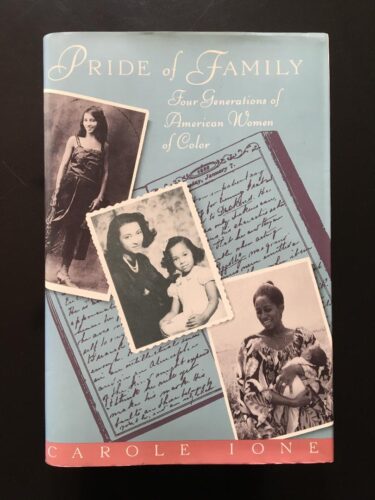

On June 9, Brandon Butler and Peter Jaszi took part in a virtual workshop for BIO on fair use for biographers. Here, Butler and Jaszi answer two follow-up questions on the topic. You can see a recording of the workshop  During this historic summer of 2020, Black Lives Matter is garnering support nationally and internationally. For biographers and readers of biography, black lives matter, and writing black lives matters. Six BIO members will contribute essays to the July issue of The Biographer’s Craft about black lives, racism, and how they relate to biography. Here, in the meantime, are biographies of African-Americans by BIO members.

During this historic summer of 2020, Black Lives Matter is garnering support nationally and internationally. For biographers and readers of biography, black lives matter, and writing black lives matters. Six BIO members will contribute essays to the July issue of The Biographer’s Craft about black lives, racism, and how they relate to biography. Here, in the meantime, are biographies of African-Americans by BIO members.