On Being “Frank”

By Eric K. Washington

Carole Ione’s work includes the opera The Nubian Word for Flowers, a co-creation with Pauline Oliveros that debuted in 2017.

One could say Carole Ione, also known professionally as IONE—a playwright, poet, diarist, and frequent co-creator with her longtime spouse, the late composer Pauline Oliveros —has grown accustomed to long waits. As chair of BIO’s Black Lives Matter Committee, I recently had the privilege of informing Ione that Frances Anne Rollin Whipper (1845–1901) would be the namesake of a new $2,000 fellowship next spring, to be offered for a biography-in-progress of an African American figure. Whipper claimed the distinction of being the first known African American biographer in 1868, when just before her marriage she published—under the pen name “Frank A. Rollin”—Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany, about a Black abolitionist journalist, physician, and Union Army officer.

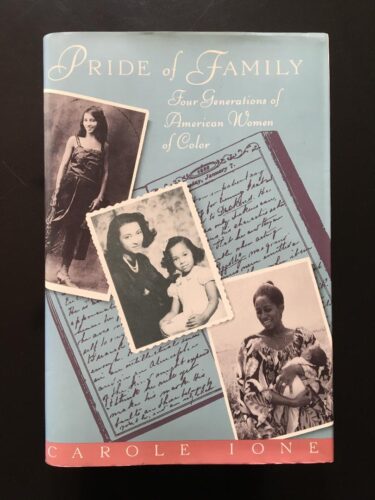

Ione had played a key role in reviving her predecessor’s nearly forgotten merit. In 1991, 90 years after Whipper’s death, Ione traversed uncharted bloodlines to an unknown great-grandmother—her book, Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, was at once biography and memoir. (The book was edited by Ileene Smith, winner of BIO’s 2019 Editorial Excellence Award.) Ione’s personally, long-awaited book received good reviews, yet nevertheless seemed ill-timed, for her publisher (Summit Books) went out of business right after its release. But nearly three decades later, Carole Ione appears no less heartened for good news.

Carole Ione’s Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color was a New York Times Notable Book.

Eric K. Washington: What was your thought when you heard your great-grandmother, Frances Rollin, was to be the namesake of a biography fellowship?

Carole Ione: Oh, it really was like a dream coming true through centuries. When I was working on my book I was obsessed with her. There’s this line in her diary in which she said she wanted to “make her mark in literature,” but many things prevented that from happening fully. She was acclaimed for the book when it came out, and then she had much other writing that was interrupted by the difficulties of the Reconstruction Congress. Her political activism remained intact, and she gave her all [to] raising kids in Washington. Yet I’ve always felt the sort of longing in her remark. And when I heard the news, I felt that it had happened.

EKW: Frances Rollin was a remarkable woman, with whom you had much in common as a writer and a diarist. Yet somehow you didn’t become acquainted with her until adulthood?

CI: Yes, my mother had mentioned that there was someone, but it was very vague. I was a freelance writer in the 70s, scrambling for all kinds of stories. Ms. magazine was happening, and I remembered something about the women in my family . . . something about a diary. My mother had sent the diary to Dorothy Sterling [another writer, then working on We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century, W. W. Norton, 1984], who sent me the diary.

So I discovered my great-grandmother [Frances Rollin, who married lawyer William J. Whipper] as an adult with children. I had a good education, but there were no African American studies at the time. When I opened the book, I said “how could I have not known about this woman my whole life?” So part of my research was in finding out, you know, why the women in my family were not forthcoming about their own lives.

The men in the family were quite renowned in their way—William S. Whipper [noted abolitionist, not to be confused with Frances’s husband, William J. Whipper], and my grandfather, Leigh Whipper [Frances’s son, the legendary stage and screen actor] . . . but when I tried to find out about the women, [the family] had very little to say. So as I began to write I looked toward this woman, Frances Anne Rollin, as the mother who would share with me all of her secrets and her needs.

EKW: Did the nonfiction genres of biography or memoir particularly interest you prior to learning of your great-grandmother’s contribution to the field?

CI: Well, I was always interested in personal writing and personal life stories. Colette, for example, was my muse from early childhood, because my mother had a book of hers, and what mother had on her shelf I gobbled up. They were not African American stories, but they were biographies. So, yes, I was very interested.

EKW: Tell us about Frances’s nom de plume, “Frank.” Literary history abounds with instances of women writers masking their gender behind male pen names. Was this her story?

CI: You know, when I was discovering her, I was involved with the early feminist movement in a very deep way. I really was incensed that she had to publish under a man’s name. But as I deepened into my research, I found evidence that the family called her “Frank,” her nickname. Frank A. Rollin was a part of who she really was. I was relieved to find that out, and from then on, she became Frank to me, and I always wrote about her in that way.

EKW: What do you see as the lasting legacy of a 19th-century Black woman first-time biographer on a generation of 21st-century biographers?

CI: I think her perseverance in writing about a very important subject—there have been other biographies of Martin Delany, but her book is the primary source of information. And the concept of her money drying up, which happens to so many writers, then persevering through the harsh times of the political climate. Also, I think her position . . .

[Here Ione evokes her great-grandmother’s rectitude by citing a diary entry on George Washington’s birthday in 1868.]

If things continue as they are, there will be but little country to celebrate it. For myself I am no enthusiast over patriotic celebrations as I am counted out of the body politic.

CI: “Frank” was acutely aware of the worldly events around her, and of taking a stand toward better elements of life for writers and for people of color and for women.

It seems that what Ione once felt to be her great-grandmother’s unfulfilled longing to “make her mark in literature” might now be a source of inspiration. She’s thrilled by the news that next year some writer will receive BIO’s first Frances “Frank” Rollin Fellowship. “It happened!” she exclaims, conveying a sense that her patience, over a century and a half in the making, has been well rewarded.

Eric K. Washington is a BIO board member and chair of the Black Lives Matter Committee. The New York Academy of History recently awarded his biography, Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal, its Herbert H. Lehman Prize for Distinguished Scholarship in New York History.