April 18th, 2016

The following are election statements and biographies submitted by candidates for BIO’s President, Vice President, and the BIO Board of Directors. In 2016, there are nine board seats up for election, each with a two year term running from 2016 to 2018. The terms for President and Vice President are also for two years, from 2016 to 2018.

For President

Will Swift

Will Swift is a founding board member of BIO and chairs its Awards Committee. He created the Editorial Excellence Award and co-founded the BIO mentorship program. Will has served as a judge on both the Hazel Rowley and Plutarch Award committees. As president he would like to focus on four major areas: increasing BIO membership, fundraising, developing new programs to educate BIO members and the public, and increasing the visibility of BIO in the literary world. Will is working with Deidre David to set up an international biography conference at Oxford in November, 2016. He would like to see further development of such international exchanges.

Will is the author of three books on presidents and their families. His Pat and Dick: The Nixons, An Intimate Portrait of a Marriage (January, 2014) was shortlisted for the 2015 Plutarch Award and was a New York Times Editor’s Choice. His previous books are The Roosevelts and the Royals (2004) and The Kennedys Amidst the Gathering Storm (2008).

For Vice President

Deirdre A. David

Deirdre David has been a member of the BIO Board for two years; she has also served on the program and Plutarch committees. Currently, she is coordinating a collaborative effort to bring European and American biographers together for a one-day Colloquium to be held at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing in November. Last year’s Plutarch winner, Hermione Lee, will be the keynote speaker. Deirdre sees the role of the vice-president as supporting the president’s leadership and initiatives, as managing efficiently the administrative tasks involved, and as being a representative for BIO at domestic and international conferences and forums.

After a long career teaching Victorian literature and publishing five books about the novel, women’s writing, and imperialism, Deirdre became a biographer with publication of a book about the British actress Fanny Kemble, followed by a biography of the British novelist Olivia Manning. She is completing a biography of the writer Pamela Hansford Johnson, under contract to Oxford UP.

For Board of Directors

(These statements are presented alphabetically, by candidate’s last name. They will be presented on your ballot in random order.)

Kate Buford

My best-selling Burt Lancaster: An American Life (Knopf/Da Capo/UK: Aurum) was named one of the best books of 2000 by the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and others. Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe (Knopf 2010; U. of Nebraska Press paperback 2012) was an Editors’ Choice of The New York Times and won several awards. I have written for The New York Times, The Daily Beast, Film Comment and other publications, have been a featured speaker at many events, and was a commentator from 1995-2003 on NPR’s Morning Edition and APM’s Marketplace. A member of BIO and PEN, I also serve on the board of Union Settlement Association in East Harlem, NYC.

I have been involved with BIO since its formative meeting in 2009 and have served on panels at each annual conference since then. Abby Santamaria and I created the annual BIO Biblio Award in 2012, now given at each conference to a worthy archivist or research librarian, and founded Biography By Design, LLC in 2016. I currently serve on the BIO Conference Site and Program Committees. I would be honored to continue to contribute to the hard work yet to be done to expand member outreach and to raise BIO’s public profile.

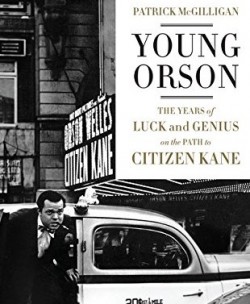

Cathy Curtis

I joined BIO in 2011 while researching my first biography. Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter was published by Oxford University Press last year. In 2017, my next book, Quicksilver: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning, will inaugurate the Oxford Cultural Biographies series.

Since 2013, I have been a member of the BIO Board; two years ago, I was elected vice president. The best part of that job has been the opportunity to work with BIO’s savvy and collegial directors. As a former chair of the Program Committee, I served as a frequent sounding board for issues pertaining to our annual conference. My other activities as vice president included writing and editing BIO communications, responding to members’ queries, helping run the Coaching Committee, and contributing a column toThe Biographer’s Craft. Recently invited to join the Rowley Prize and Plutarch Award committees, I am looking forward to engaging with a full spectrum of life writing—from proposals by newcomers to the genre to biographies by seasoned authors.

BIO is still in an adolescent phase as an organization, desperately in need of more members and increased funding even as we continue to mount stimulating, broad-based conferences featuring some of the most celebrated names in biography. As a Board member, I will continue to encourage increased participation in volunteer efforts to enlarge and sustain our indispensable organization.

Annette Dunlap

Annette Dunlap is the author of Frank, The Story of Frances Folsom Cleveland, America’s Youngest First Lady, published in hardback in 2009 and released in paperback in 2015 by SUNY Press. Her second book, The Gambler’s Daughter: A Personal and Social Memoir, was published by SUNY Press in 2012, while her third book, Charles Gates Dawes: A Life — commissioned by the Evanston (IL) History Center — will be released by Northwestern University Press in August 2016. Annette was a Hoover Presidential Scholarship recipient in 2013 and 2014 to research a biography on Lou Henry Hoover. She has appeared on C-SPAN’s First Ladies series, and her presentation at the Hoover Presidential Library on First Ladies and the Politics of Fashion aired in September 2014. She also served as a panelist at 2015’s Harding Symposium on the first ladies Florence Harding, Grace Coolidge, and Lou Hoover, which was broadcast live by C-SPAN. She is presently completing a biography of Louis Comfort Tiffany for SUNY Press.

As a Board member, Annette would like to see BIO continue to foster the professional development of biographers at all stages of their careers, and to encourage public interest in biography as a genre.

John A. Farrell

In a long career as a journalist, primarily with The Boston Globe, Jack served as White House correspondent and covered Congress, the Supreme Court and every American presidential campaign since 1980. He also was Washington bureau chief for The Denver Post, and the MediaNews chain. He has reported from Northern Ireland, Iraq, Israel and other foreign nations. In 2011, he served as a senior political correspondent for The Center for Public Integrity, a non-profit center for investigative journalism in Washington, D.C.

He is the author of Clarence Darrow: Attorney For The Damned, a biography of America’s greatest defense attorney, and of Tip O’Neill and the Democratic Century, the definitive account of House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr. and his times. He recently completed Richard Nixon: An American Tragedy, a biography of that most enigmatic 37th president of the United States.

As a board member, he would like to explore ways to expand the BIO universe by honoring and involving folks like Ken Burns, Lin-Manuel Miranda or the American Experience gang, who bring biography to life in other media.

Gayle Feldman

I am fortunate to have been associated with BIO from its first meeting, and to have seen it grow to be a grassroots organization that really does matter to members and the field. I bring an institutional memory of how far we have come and sense of where we might go.

My involvement has encompassed speaking on/moderating panels, publicity outreach, and spearheading as committee chairperson the Hazel Rowley Prize for best proposal for a first biography, which this year we are awarding for the second time. I’d like to remain on the board one more term to see Rowley Award firmly established and to ensure a smooth handover to a new chairperson.

I have worked in the publishing business my whole career, first as a book editor in London, then as a senior editor at Publishers Weekly, and now as New York correspondent for The Bookseller. I am writing my third book but first biography, a life of Bennett Cerf, under contract to Random House, the company he cofounded.

Beverly Gray

I’ve been a professor of English at USC, the longtime story editor for B-movie legend Roger Corman, a freelance journalist, and a screenwriting instructor for UCLA Extension’s celebrated Writers’ Program. My first book, Roger Corman: An Unauthorized Biography of the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking, debuted on the Los Angeles Times bestseller list. The updated paperback and ebook editions have been tastefully retitled Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. I’ve also published a second Hollywood biography, Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond.

As the hard-working local site chair of BIO’s 2012 Los Angeles conference, I was officially named a “goddess.” I have served for five years on BIO’s program committee, and have participated on a number of conference panels, either as moderator or speaker. I first became a member of the BIO board of directors in 2014. Given my movie interests, I’m working to see more attention paid to biopics and other non-traditional forms of biography. I am currently completing for Algonquin Books the tentatively-titled Where Have You Gone, Mrs. Robinson?, an account of the legacy of The Graduate, timed to reflect the fiftieth anniversary of the film’s release.

Dean King

Dean King is a nationally best-selling author of nine books, including Skeletons on the Zahara, The Feud: The Hatfields & McCoys, and Patrick O’Brian: A Life Revealed. While conducting groundbreaking research around the globe, Dean has trekked the Sahara on camels, crossed the Snowy Mountains on the Tibetan Plateau in China on foot, gone undercover in Catalan France, and been shot at in West Virginia. He has appeared on NPR, the BBC, ABC World News Tonight, and as the lead storyteller on two History Channel documentaries. His writing has appeared in Esquire, Granta, Garden & Gun, National Geographic Adventure, Outside, New York Magazine, the New York Times, and Virginia Living, where he is a contributing editor. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Library of Virginia Foundation and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and is a co-founder of the award-winning literary nonprofit James River Writers.

As a Board member, he would like to help the organization grow and broaden its appeal to a wider range of nonfiction writers. He would also like to help it improve its financial footing and continue to improve the quality and appeal of its conference. He has worked with the programming committee that past two years, contributing to a panel moderating guideline and helping to devise several panels.

Heath Lee

Heath comes from a museum education, preservation, and program background. She holds a B.A. in History with Honors from Davidson College, and an M.A. in French Language and Literature from the University of Virginia. She started her museum career at the Levine Museum of the New South in Charlotte, North Carolina, and has since worked as a consultant for southern house museums such as Stratford Hall, Robert E. Lee’s birthplace, and Menokin Plantation. She recently served as the Coordinator of the History Series for Salisbury House & Gardens, a 1920’s house museum in Des Moines, Iowa. She currently works as the Editorial Assistant forThe Virginia Magazine of History and Biography.

Potomac Books, a division of the University of Nebraska Press, published Heath’s first book, Winnie Davis: Daughter of the Lost Cause, in 2014. Winnie won the 2015 Colonial Dames of America Annual Book Award as well as a Gold Medal for Nonfiction writing from the Independent Publisher 2015 Book Awards. Heath is currently working on her second book, a group biography entitled The Reluctant Sorority: the story of the courageous wives of officers who were Prisoners of War or Missing in Action during the Vietnam War.

If elected to the Board, Heath would like to see BIO grow its membership with those in the 35-55 demographic. She would also like to help BIO launch a program to help funnel biographers into speaking engagements with established museums and schools. She believes the future of BIO depends upon its members being “out there” in the communities they live in, selling their ideas-and their books, while also helping our museums and schools access BIO’s superb speakers.

Hans Renders

Hans Renders, a board member of BIO, lives in Amsterdam and holds a chair in History and Theory of Biography. He is the director of the Biography Institute, Groningen University and Vice-President of La Société de Biography/Biography Society . He is the editor of Le Temps des Médias; of Quaerendo. A Quarterly Journal from the Low Countries; and of ZL. Literary-historical magazine. He is a book critic for the newspaper Het Parool; and is also a Member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for the History and Theory of Biography (Vienna).

Biographers write better biographies when they’re aware of the theoretical implications of their work. In my experience, there’s no necessary gap between academic justified biography and biography which is interesting for the general public. We all want a biography to be a good read. But poor writing is everywhere, in and outside the academic world. I hope to bring in the European perspective to keep BIO a real international organization.

I’m currently working on the biography of Theo van Doesburg (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theo_van_Doesburg), the painter, poet and art theorist who founded together with Piet Mondrian the Style Movement.

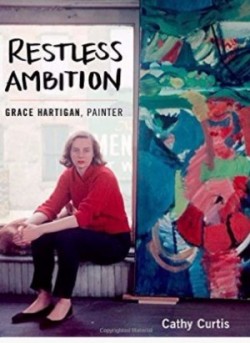

Rosemary Sullivan won the 2016 Plutarch Award for Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva. Read more about the Plutarch, this year’s semi-finalists, and the winners of special awards for excellence here, and look for more on Sullivan and her honor in the July issue of The Biographer’s Craft.

Rosemary Sullivan won the 2016 Plutarch Award for Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva. Read more about the Plutarch, this year’s semi-finalists, and the winners of special awards for excellence here, and look for more on Sullivan and her honor in the July issue of The Biographer’s Craft. In collaboration with the

In collaboration with the