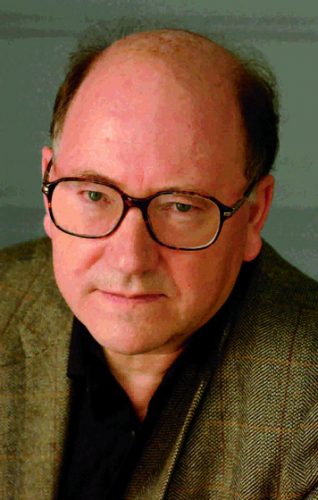

Exploring the Depth of Subjects’ Souls: An Interview with 2018 BIO Award-Winner Richard Holmes

By James Atlas

A great biographer is someone who writes great biographies. A revolu- tionary biographer is someone who writes revolutionary biographies. Since the publication of his massive, ingenious, and mesmerizing debut, Shelley: The Pursuit, published when he was twenty-nine, Richard Holmes has written seven biographies and assembled four collections of biographical essays uniform only in their strange, unclassifiable aura. Holmes’s essential principle is not simply to write about his subjects but to inhabit them—and, to borrow his own description of his method, to haunt them.

All biographers aspire to know the people they’re writing about, to get beneath their skin, as Claire Tomalin, that other master of the craft, puts it; Holmes aspires to become them. In the quest of this goal—the source of his power as a biographer—he has perambulated with the ghost of Dr. Johnson in St. James Square, tracked Shelley to the site of his drowning in the Gulf of La Spezia, shadowed Coleridge to every corner of the Lake District. Untethered to the library, he has gone up in a hot-air balloon and risked his life in a sailing adventure that required a rescue by helicopter in the course of his research. But Holmes’s greatest journey has been inward, to the depths of his subjects’ souls. He has gone, he writes, in This Long Pursuit (his new collection of essays), not just to “the blue-plaque place” but to “the temporary places, the passing place, the lost places, the dream places” where the real story is.

In the terrestrial sense, he lives in London and Norfolk with his partner, the novelist Rose Tremain.

James Atlas: One of your most famous innovations as a biographer has been the idea of biography as not simply a recording but a “haunting,” a “pursuit” of one’s subject. What is the origin of this method, first articulated in Footsteps and a ruling principle of your work ever since? Has it been refined and how does it continue to preside over your work?

Richard Holmes: I think the idea of biography as a journey of pursuit actually goes back a long way, such as in A. J. A. Symons’s The Quest for Corvo (1934), and there are elements of a pursuit even in [Edward] Trelawny’s wonderful and disreputable Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron (1858). My pursuit began quite naively as a lonely teenager simply finding that I was “walking with” Robert Louis Stevenson (who died in 1894) through the remote Cevennes hills in southern France. But it was extraordinarily vivid, almost a continuous hallucination over 200 kilometers, lasting many days. It was perhaps an extension of that experience that many people have in their childhoods of inventing an “imaginary friend.” But my friend eventually turned out to be real. The pursuit of Shelley, Johnson, Coleridge, Herschel, and the others that followed was just a sophisticated version of this, with additional documentation, so to speak. It is a pursuit through space (geography) but also through time (history).

JA: You speak of empathy as the biographer’s dominant task. How is this difficult, imaginative feat to be achieved? Why is it the crucial component of his art?

RH: Yes, I have called empathy the most necessary and most perilous of biographical gifts. Philosophically, you can never know how another person actually feels, but imaginatively I believe you can. So biography not only attempts to narrate the events of a life—to tell the story—but to enter imaginatively into it and tell the inside story. It requires a long, faithful, passionate immersion in letters, journals, contemporary memoirs, places, and objects. And simply immense, insane amounts of time spent in your subject’s company—somewhere between three and 10 years perhaps. The process is something I have described as an extended handshake. My feeling is that at the end of a biography the reader should know not only what this person “was like,” but what it was “like to be” this person.

JA: Could you bring us up to date on the Master’s degree program in Biography at the University of East Anglia? Is it still a going concern?

RH: I originally launched and designed this MA in Biography in 2001, and taught it for some five years, and thereafter contributed an occasional lecture. (I give a detailed account of the program and of why I think biography is so valuable to teach in my most recent book, This Long Pursuit.) My colleague, the biographer Kathryn Hughes, took it over and is still running it with great success, now as the MA in Biography and Creative Non-Fiction, with some dozen students every year (several American). The two other teachers are both accomplished biographers: Ian Thompson (Primo Levi, 2002) and Helen Smith (The Uncommon Reader, 2017).

JA: Could you say something about your current project? What are you writing now?

RH: Ah, the “current project”! Not sure I think quite like that, more like the “current distractions” (in the plural). Right at this moment I am writing a short study of the inspirational American astronomer and teacher (Nantucket and Vassar) Maria Mitchell (born 1818), who also toured the observatories of Europe. After The Age of Wonder I am still very interested in the way scientific discovery has steadily (sometimes violently) transformed our imaginative vision of the world around us, especially in the years immediately before Darwin’s theory of evolution became the new orthodoxy. Whether this will be done through a traditional biography, a group biography, or some much more personal footstep, I am still not sure. One provoking but strictly working title has been Tennyson and the Kraken, referring to the legendary deep-sea monster which threatens to surface in one of Tennyson’s earliest poems and which haunted the Victorian unconscious—a symbol of all kinds of modern disruption—for a generation.

James Atlas is the author of The Shadow in the Garden: A Biographer’s Tale and the founder of the Penguin Lives Series.

TBC: What was it like being president?

TBC: What was it like being president?