April 17th, 2014

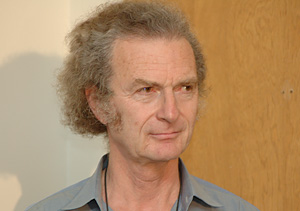

Jim Elledge

Jim Elledge is the author of Henry Darger, Throwaway Boy: The Tragic Life of An Outsider Artist, a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award for gay memoir/biography and for the Publishing Triangle nonfiction award. A published poet, Elledge is a professor of English at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. At the BIO conference, he will join Cassandra Langer, Barry Werth, and Brian Halley on the panel “Twice Marginalized: The Challenges of Writing About Little-Known Gay and Lesbian Subjects.”

TBC: The bizarre works of self-taught artist and unpublished novelist Henry Darger (1892-1973) have inspired both fascination and horror. What made you decide to write his biography?

Jim Elledge: Another poet had told me about Darger’s work. Doing the initial research on the Internet, I was appalled by what I was reading. It was all very negative about Darger himself. So I was very interested to see what my reaction would be to the paintings. The first time I saw them, at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, I was overwhelmed by the beautiful color and what he was able to do without having any real background in art, but I also did not feel the images I was seeing indicated anything close to his being a pedophile or serial killer, as some had thought.

When I saw the little figures in Darger’s paintings—the little girls with penises, chased by adult men and captured and crucified and strangled—it struck me that it was perhaps some kind of representation of gay boys. I had done some research into gay life in the 1800s for two other books that I published, and I realized from that research that gay men had historically used hermaphroditic figures to represent themselves. They saw the figures as a physical representation of the idea they had come up with to explain their orientation—a female soul in a man’s body, attracted to men as heterosexual women are.

Initially, I thought I’d write an essay and then some kind of critical book, and then I realized I knew nothing about art. So what was left was a biography.

TBC: How did you cope with what must have been a dearth of documentation of the life of a man who was institutionalized as a youth and spent his adult life working at menial jobs and living in a single room?

JE: There really isn’t a huge amount of material, simply because he was from a very poverty-stricken background. He was just a kid who had been, like many kids of that time, tossed out and ignored or abused. So what I had to do was look at what there was.

He wrote an autobiography that has never been published. There are many details in it that helped a lot, though he was very coy and hinted a lot about stuff. I read it so many times that I started seeing where he was hedging and seeing patterns in his writing that for me opened up a lot of possibilities.

I also had to look at what other boys of his approximate age in Chicago at the same time were up to. There’s a lot of sociological material that talks about what boys typically did in those days and the kind of trouble they got into. What he was hinting about was what other boys were going through at the same time, in that particular neighborhood, in similar types of institutions. I found so much that really connected with Darger, and given what he said in the autobiography, it seemed correct to put the two together.

When you have someone like Darger and you have this huge mystery—what do those figures mean?—there’s no way to discover it through the paintings themselves. The paintings certainly don’t tell us he was also a novelist. There are lots of clues in the novels about his sexuality.

I found the key to the torture of the children in the first novel. That was an important way of validating what I was doing. I wasn’t sure I was doing the right thing initially, and then I found this and I said, yes, this is the way it’s got to be.

Evan Thomas

Biographers know that dealing with a subject’s family requires the negotiation skills of a trained diplomat, but that it can also be extraordinarily rewarding. The “Getting the Family on Board” panel at this year’s BIO conference will benefit from the experience of veteran biographer and historian Evan Thomas, whose most recent book is Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World. Evan was kind enough to answer some questions from Beverly Gray, moderator of the panel.

Beverly Gray: As a biographer and historian, you’ve covered a wide range of subjects: naval heroes, presidents, spies, politicians. How do you choose your topics? Can you identify a common thread that ties together your eight major book projects?

Evan Thomas: I am very interested in the rise (and fall) of American power after World War II and the role of political and social establishments. I am also interested in war—as the ultimate test of men (and sometimes women) and as the source of so much heroism and folly.

BG: In researching Robert F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower, you’ve have to deal with two important presidential families. Were there special challenges in seeking information from the famously self-protective Kennedys?

ET: The Kennedys do present a challenge, but not an insuperable one. The key is patience and appealing to their self-interest.

BG: In the Acknowledgments of your Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World, you especially praise Ike’s granddaughter, Susan Eisenhower, calling her an “able historian.” In your opinion, what makes an able historian? And how did Susan’s insights contribute to your book?

ET: Susan Eisenhower has the unusual ability to step back from her family and see her grandfather with some detachment. That is not to say that she doesn’t care about his place in history—she has led the opposition to the Frank Gehry-designed Eisenhower Memorial. But she is not kneejerk and she has written enough history to appreciate the difficulties and duties of historians. She was immensely helpful in getting her late father, John, to talk to me.

BG: When researching a biography, how (and when) do you approach your subject’s family? Have you devised any personal rules for working successfully with family members?

ET: The best rule is to not hide the ball, to tell them early on what you are up to and—in most cases—to show them the manuscript so there are no surprises at the end. This does not mean ceding control over the product, but rather trying to build trust by full disclosure.

BG: Have you ever been in situations where you’ve had to coax a family member into speaking honestly and for the record? Have you ever had to offer specific concessions to someone who’s fearful about dishonoring a relative’s reputation?

ET: I have always tried to be mindful of their feelings and to not gratuitously inflict pain. With patience and understanding, you can usually find ways to print virtually everything.

BG: You will be sharing this panel with presidential historian Will Swift, whose new book explores the marriage of Pat and Dick Nixon, as well as Brian Jay Jones, author of Jim Henson: The Biography. What do you look forward to learning from these two biographers?

ET: I hope to learn a lot from them about how to deal with the families!

In writing about Rockwell a second challenge surfaced that is more common to the experience of many, if not all, biographers writing about a figure of the past—the topic of sex. “I consider myself an art expert, but not a sex expert. So when I write about an artist, I do not try to come to any conclusions about sex. I merely try to present the evidence about a subject’s sexual habits and let readers draw their own conclusions.

In writing about Rockwell a second challenge surfaced that is more common to the experience of many, if not all, biographers writing about a figure of the past—the topic of sex. “I consider myself an art expert, but not a sex expert. So when I write about an artist, I do not try to come to any conclusions about sex. I merely try to present the evidence about a subject’s sexual habits and let readers draw their own conclusions.