July 22nd, 2018

Andrew D. Scrimgeour of Cary, North Carolina, has received the 2018 Hazel Rowley Prize of Biographers International Organization (BIO) for best book proposal from a first-time biographer. Scrimgeour’s proposal for The Man Who Tried to Save Jesus: Robert W. Funk and The Jesus Seminar—about one of the most controversial figures in modern biblical scholarship—was selected by distinguished biographers Stacy Schiff and James Atlas.

Scrimgeour’s proposed biography would chart Funk’s career, which revolutionized the study of biblical texts. For two decades, through his signature creation, the Jesus Seminar, he attracted more sustained media attention in the United States than any religious authority other than the Pope.

In addition to the $2,000 cash award, the Rowley Prize helps a promising first-time biographer by providing introductions to prominent agents. The prize also includes a year’s membership in BIO and publicity on the BIO website and The Biographer’s Craft newsletter.

The prize was named in memory of Hazel Rowley (1951-2011). A BIO enthusiast from the inception of this organization, she understood the need for biographers to help one another on the path to publication. Before her untimely death, she published four books: Christina Stead: A Biography (a New York Times “Notable Book”); Richard Wright: The Life and Times (a Washington Post “Best Book”); Tête-à-Tête: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre; and Franklin and Eleanor: An Extraordinary Marriage.

You can find more information about the prize and the application process here.

Published under: Awards, Biography, Rowley Prize

Tags: Andrew D. Scrimgeour

May 23rd, 2018

Caroline Fraser won the 2018 Plutarch Award for Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The book had previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, among other honors. Fraser received her award at the ninth annual BIO Conference on May 20.

Caroline Fraser won the 2018 Plutarch Award for Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The book had previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, among other honors. Fraser received her award at the ninth annual BIO Conference on May 20.

The Plutarch is the world’s only literary award given to biography by biographers. Named after the famous Ancient Greek biographer, the Plutarch is determined by secret ballot from a formal list of nominees selected by a committee of distinguished members of the craft. The award comes with a $1,000 honorarium.

BIO’s Plutarch Award Committee for 2018 was:

Anne C. Heller, chair

Kate Buford

Nassir Ghaemi

Brian Jay Jones

Andrew Lownie

Julia Markus

J.W. (Hans) Renders

Ray Shepard

Will Swift, ex-officio

You can find out more information about the Plutarch Award here.

Published under: Awards, Biography, News, Plutarch Award

May 9th, 2018

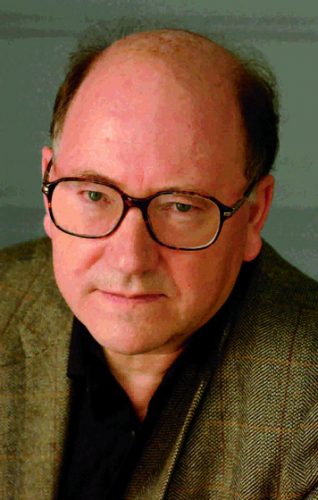

Photo: Stuart Clarke

Acclaimed literary biographer Richard Holmes will receive the 2018 BIO Award at BIO’s upcoming conference in New York and give the keynote speech on May 19. As a preview of that, James Atlas interviewed Holmes; you can read the interview here.

Published under: Awards, BIO Award, Biography, Conference, Interview, News

Tags: James Atlas, Richard Holmes

March 11th, 2018

Natalie Dykstra and Marina Harss will each receive $2,500 as the winners of the first Robert and Ina Caro Research/Travel Fellowship. BIO introduced the fellowship in 2017 to honor the Caros’ work and help biographers establish a sense of place to delineate their subject’s character. You can read more about Dykstra, Harss, and the fellowship in the March Letter from the Vice President by Deirdre David.

Published under: Awards, Caro Research/Travel Fellowship, News

February 14th, 2018

Photo: Stuart Clarke

British author Richard Holmes, beloved for his biographies and memoirs about writing biography, is the winner of the ninth annual BIO Award. BIO bestows this honor on a colleague who has made a major contribution to the advancement of the art and craft of biography. Previous award winners are Jean Strouse, Robert Caro, Arnold Rampersad, Ron Chernow, Stacy Schiff, Taylor Branch, Claire Tomalin, and Candice Millard. Holmes will receive the honor on May 19, at the 2018 BIO Conference at the Leon Levy Center, City University of New York, where he will deliver the keynote address.

Holmes’s The Age of Wonder was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize, and won the Royal Society Prize for Science Books and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. He has written many other books, including Falling Upwards, an uplifting account of the pioneering generation of balloon aeronauts, and the classicFootsteps. Its companion volumes, Sidetracks and This Long Pursuit, complete a trilogy that explores the Romantic movement biographer at work. Holmes’s first biography, Shelley: The Pursuit, won the Somerset Maugham Prize; Coleridge: Early Visions won the 1989 Whitbread Book of the Year Award; Coleridge: Darker Reflections won the Duff Cooper and Heinemann Awards; and Dr. Johnson & Mr. Savage won the James Tait Black Prize.

Holmes holds honorary doctorates from the universities of East Anglia, East London, and Kingston, and was professor of biographical studies at the University of East Anglia from 2001 to 2007. He is an Honorary Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, a Fellow of the British Academy, and was awarded the OBE (Order of the British Empire) in 1992. He lives in London and Norfolk, with the novelist Rose Tremain. TBC will have an interview with Holmes in an upcoming issue.

Published under: Awards, BIO Award, Biography, News

Tags: Richard Holmes

February 1st, 2018

BIO’s Plutarch Award Committee has chosen the four books highlighted below as the finalists for this year’s Plutarch Award, the only international literary award for a biography that is chosen by fellow biographers. BIO members will have three months to read the finalists and vote for the winner. The Plutarch Award will be presented on Saturday, May 19, at the Ninth Annual BIO Conference in New York.

To see a list of the nominees for 2018 and learn more about the Plutarch Award, go here.

-

-

Ali: A Life, by Jonathan Eig, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Eig interviewed nearly everyone still living who knew Muhammed Ali, including his ex-wives, and crafted those interviews, along with much additional primary source material, into a deft, enlightening, and enlivening narrative of the life of an American icon.

-

-

Richard Nixon: The Life, by John A. Farrell, Doubleday: In an elegantly written, expertly researched, and commanding narrative of the rise and fall of Richard Nixon, John A. Farrell has created in a single volume a rich and deeply affecting portrait of perhaps the most complex, fascinating, and darkest of American presidents.

-

-

Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, by Caroline Fraser, Metropolitan: Fraser’s work is both a haunting depiction of Laura Ingall Wilder’s life, work, and collaboration with her flamboyant, unstable daughter, the writer Rose Wilder Lane, and a surprising history of how the pioneer experience led to American conservative values. Fraser demonstrates that literary history is woven into the very fabric and destiny of the nation.

-

-

Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror, by Victor Sebestyen, Pantheon: The first major biography in English of Vladimir Lenin in twenty years, Victor Sebestyen’s riveting work draws on newly available archives and the author’s gift for sustaining a highly suspenseful narrative to present a far-reaching and very human portrait of the father of the Russian Communist state.

Published under: Awards, News, Plutarch Award

January 16th, 2018

Here are the nominees for the 2018 Plutarch Award, honoring the best biography published in 2017, listed in alphabetical order by author:

-

-

Grant, by Ron Chernow, Penguin: In his latest magisterial work, Pulitzer Prize winner Chernow (Washington, etc.) persuasively resuscitates and reinterprets the much-maligned Civil War general and U.S. president as a hero for our time, a leader whose humane instincts and far-sighted policies began to heal the war-torn nation and forge a modern American political conscience.

-

-

Ali: A Life, by Jonathan Eig, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Eig interviewed nearly everyone still living who knew Muhammed Ali, including his ex-wives, and crafted those interviews, along with much additional primary source material, into a deft, enlightening, and enlivening narrative of the life of an American icon.

-

-

Richard Nixon: The Life, by John A. Farrell, Doubleday: In an elegantly written, expertly researched, and commanding narrative of the rise and fall of Richard Nixon, John A. Farrell has created in a single volume a rich and deeply affecting portrait of perhaps the most complex, fascinating, and darkest of American presidents.

-

-

Milosz: A Biography, by Andrzej Franaszek; trans. by Aleksandra Parker and Michael Parker, Harvard: Franaszek’s biography of the great Polish poet Czelaw Milosz, translated from Polish, traces the immensely complex political and moral life of a writer and diplomat caught in the crosscurrents of twentieth-century European xenophobia, nationalism, and war, with 1951, when Milosz decided to break with his homeland and with communism, as the turning point. A highly dramatic rendering of a relevant life.

-

-

Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, by Caroline Fraser, Metropolitan: Fraser’s work is both a haunting depiction of Laura Ingall Wilder’s life, work, and collaboration with her flamboyant, unstable daughter, the writer Rose Wilder Lane, and a surprising history of how the pioneer experience led to American conservative values. Fraser demonstrates that literary history is woven into the very fabric and destiny of the nation.

-

-

Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel, by Francine Klagsbrun, Schocken: A vivid portrait of Israel’s first female prime minister, Lioness is a stellar example of how to narrate aspects of a contradictory and often stereotyped character in a nuanced, fresh, and clear-eyed way. With scrupulous research and contextualization, Klagsbrun makes an eloquent case for the rehabilitation of the activist “Iron Lady” of Israeli politics as a world figure.

-

-

Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast, by Megan Marshall, Houghton: With extraordinary steadiness of voice throughout, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Megan Marshall (Margaret Fuller) depicts the complex life of the poet Elizabeth Bishop. She effectively and unobtrusively uses her own interactions as a student in Bishop’s Harvard classes to cast light on Bishop’s character and ultimately to illuminate how the biographer is drawn to her craft. A brave, groundbreaking work.

-

-

Jane Crow: The LIfe of Pauli Murray, by Rosalind Rosenberg, Oxford: With impeccable research and a compelling recounting, Rosenberg tells the full story, for the first time, of remarkable twentieth-century American social activist Pauli Murray. “A minority within a minority,” Murray used her complicated identity—mixed race born into the Jim Crow South, a woman, and a transsexual—to tear down seemingly impenetrable social justice barriers. This timely biography ensures that Murray’s unique contributions to American history are duly recognized.

-

-

Lenin: The Man, the Dictator, and the Master of Terror, by Victor Sebestyen, Pantheon: The first major biography in English of Vladimir Lenin in twenty years, Victor Sebestyen’s riveting work draws on newly available archives and the author’s gift for sustaining a highly suspenseful narrative to present a far-reaching and very human portrait of the father of the Russian Communist state.

-

-

Gorbachev: His Life and Times, by William Taubman, Norton: This first full-fledged biography of Soviet-system reformer Mikhail S. Gorbachev, an idol of the West and an anti-hero among many in his own country, has been long awaited and is indispensable to understanding the Russia of our times. From probing original research, Pulitzer Prize- winner Taubman (Khrushchev) builds a complex and nuanced portrait of a leader who diminished the role of the Communist Party, with Perestroika and glasnost as a result, and changed the face of the former Soviet Union.

BIO PLUTARCH AWARD COMMITTEE MEMBERS, 2018:

Anne C. Heller, chair

Kate Buford

Nassir Ghaemi

Brian Jay Jones

Andrew Lownie

Julia Markus

J.W. (Hans) Renders

Ray Shepard

Will Swift, ex-officio

Published under: Awards, News

December 10th, 2017

By Dona Munker, TBC New York Correspondent

Cathy Curtis presents the Editorial Excellence Award to Robert Weil.

On November 8, Robert Weil, editor-in-chief and publishing director of Liveright, an imprint of W. W. Norton, received BIO’s fourth annual Editorial Excellence Award. He joins Nan A. Talese, Jonathan Segal, and Robert Gottlieb, as winners of this honor. Introduced by one of his authors, Thomas Jefferson biographer Annette Gordon-Reed, Weil said that he thinks he may have become an editor because editing fulfills “a yearning to rescue and nurture.” The evening, which also included a panel discussion, was cosponsored by the Leon Levy Center for Biography at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Follow this link to view his speech and hear Gordon-Reed and five other biographers Weil nurtured share what makes an editor legendary.

Attendees at the event included, from left to right: Kai Bird, Will Swift, Julia Reidhead, Linda Gordon, Ruth Franklin, Annette Gordon-Reed, David Levering Lewis, Robert Weil, Yunte Huang, and Max Boot.

Published under: Awards, Editorial Excellence Award

Tags: Annette Gordon-Reed, Robert Weil

Caroline Fraser won the 2018 Plutarch Award for Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The book had previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, among other honors. Fraser received her award at the ninth annual BIO Conference on May 20.

Caroline Fraser won the 2018 Plutarch Award for Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. The book had previously won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, among other honors. Fraser received her award at the ninth annual BIO Conference on May 20.