|

May 2023 | Volume 18 | Number 3

|

FROM THE EDITOR

For the first time in four years, the BIO Conference was held in person at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City and by all accounts seeing each other again was an overwhelming success. The conference had one of the highest attendant rates in its history, and following 2023 BIO Award Winner Kitty Kelley’s keynote address on Saturday, outgoing BIO President Linda Leavell announced that Kelley had made a gift to BIO of $1 million. You’ll find the text of Kelley’s address below, as well as a recap of the Plenary Session with 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner Beverly Gage. Following that TBC Correspondent Etta Madden interviewed J. C. Hallman, author of the forthcoming Say Anarcha, for an exploration of the emerging field of speculative biography. Next month’s TBC will share more about the conference’s panels, along with photos. (And we love candids–so send us yours!)

Please send along your news and updates for the June Insider. The inbox is open. Sincerely,

Holly

|

|

|

|

FROM THE BIO CONFERENCE

BIO Conference Recap: BIO Award-Winner Kitty Kelley’s Speech

Kitty Kelley delivering the keyote address at the 2023 BIO Conference. Photo by Brennan Cavanaugh.

Kitty Kelley delivering the keyote address at the 2023 BIO Conference. Photo by Brennan Cavanaugh.

By now you likely know that Kitty Kelley won the 2023 BIO Award. On Saturday, May 20, at the 2023 BIO Conference, it was also announced that Kelley will make a gift of $1 million to BIO, to be given over the course of five years. You can read more about that here. (Look to next month’s Insider for more information as well.)

If you were one of the lucky attendees in the Proshansky Auditorium on that Saturday afternoon, then you would have heard Kelley’s keynote address. If you were not there or would like to revisit Kelley’s vivid descriptions of her journey through a life in biography and what the genre means to her, you may do so here.

BIO Conference Recap: James Atlas Plenary with Blanche Wiesen Cook and Beverly Gage

Blanche Wiesen Cook (left) and Beverly Gage (right). Image courtesy of Steve Paul.

Blanche Wiesen Cook (left) and Beverly Gage (right). Image courtesy of Steve Paul.

by Holly Van Leuven

The James Atlas Plenary, the first session of the 2023 BIO Conference, took place on Saturday, May 20, at 9:00 a.m. The event featured a conversation between Blanche Wiesen Cook, author of Eleanor Roosevelt, a three-volume biography (Viking, 1992, 2000, and 2016); and Beverly Gage, author of G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Viking, 2022), winner of the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

Both Cook and Gage remarked upon the phenomenon of finding the subjects of their biographies while researching and writing other books: For Cook, Roosevelt became a person of interest while she worked on The Declassified Eisenhower: A Startling Reappraisal of the Eisenhower Presidency (Penguin, 1984), and Gage decided to dig deeper into the life of the first director of the FBI while she wrote The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror (Oxford University Press, 2009).

The speakers provided detailed insights into the politics and careers of their subjects. Cook, for example, drew parallels between Eleanor Roosevelt’s coalition-building efforts to expand democratic principles and the “hopeful moment for democracy,” as Cook characterized it, that defines the present day. Gage spoke of “the long tradition,” borne out of the 1960s and 1970s, of liberals and leftists “supporting the FBI in moments of political stress as a kind of bulwark against demagogue,” which has resurfaced in the current American political landscape.

Both authors faced considerable challenges writing about their various subjects. “When I was working on Eisenhower,” Cook shared, “everything I wanted to know was secret or top secret. And so, I always say, ‘Never go anywhere without your gang. . . .’ I called a meeting of some of my pals at CCR and the ACLU.” From there, Cook and the advocates she worked with joined with Representative Bella Abzug to draft amendments to the Freedom of Information Act. “And through the Freedom of Information Act,” Cook said, “I got FBI files.” This drew a round of applause from the audience.

Concerning her research on Hoover, Gage said: “I think many biographers come to their subjects because they admire their subjects, they want to enliven their subjects, they want to bring their subject’s story into the world in some way. Right? It’s been forgotten. There’s a set of compelling ideas. There’s something admirable. So . . . I was not approaching my subject from that perspective.” She continued, “It was an interesting experience to spend so long with someone that I did not particularly admire when I started out, though [I] admired [him] a little more when I was done, after more than a decade of sitting with his legacy. And yet, I would make a bid to the people in this audience that it is as important to study those that we do not like, and that we do not admire.”

The two authors noted some surprising common ground between Roosevelt and Hoover, who had vastly different politics most of the time. “Eleanor Roosevelt was an activist anti-communist, and anti-Stalinist, Cook said, “but she was a globalist. And I think we need that part of her vision.”

Gage responded by noting that Hoover had served under four Democratic presidents and four Republican presidents. “They all kept him on, in part, because they were . . . maybe a little concerned about what he had in his files and about his own independent power. But they also were operating within a consensus that even Eleanor Roosevelt was part of, a kind of broad anti-communist consensus, a world in which the two parties were not so ideologically divided as they are today.”

Cook’s final comment in the plenary was spoken in regards to the current political climate, but the sentiment could apply to the field of biography: “We are at a time of shifting and new vision. And we don’t know where it’s going.”

Recaps of BIO Conference panels that explored some of the shifting sands of biography will be featured in future issues of The Biographer’s Craft.

|

|

|

|

CORRESPONDENTS' DESK

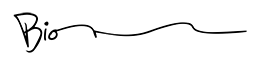

Exploring Speculative Biography Through J. C. Hallman’s ‘Say Anarcha’

J. C. Hallman, author of Say Anarcha.

J. C. Hallman, author of Say Anarcha.

by Etta Madden

Editor’s Note: Speculative biography combines the traditional aspects of biography with fiction-writing techniques that allow writers to flush out familiar characters in unfamiliar ways, or to portray little-known subjects with the depth that history—for a variety of reasons—has not been able to afford them otherwise. BIO member Etta Madden interviewed J.C. Hallman, author of the forthcoming Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health (Macmillan, June 2023) to explore this increasingly popular subgenre of biography.

In April 2018, a statue of J. Marion Sims, the controversial “Father of Gynecology” and founder of the New York Woman’s Hospital, was removed from Central Park in protest of the physician’s numerous experiments on enslaved women. Two years earlier, protesters of the statue and Sims’s work had begun chanting: “Say her name! Anarcha!”—the name given to the woman who, beginning in 1846, endured more than 30 “experiments” under the gynecologist’s hands. In June, Henry Holt releases J. C. Hallman’s Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health, a dual biography that expands what we know about Sims and this female subject. Hallman, a former Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow, recently responded to questions about his writing of this book for The Biographer’s Craft, an appropriate subject for the newsletter given that it falls into the subgenre of speculative biography.

Similar to Tiya Alicia Miles’s All That She Carried: The Story of Ashley’s Sack (Random House, 2021), Hallman’s narrative is built upon years of extensive research. But—as with the story of Ashley as explored by Miles—there are elements included of both Anarcha’s and Sims’s stories that are not documented. According to Hallman, those gaps can only be filled by speculation, based on the evidence which does exist.

Say Anarcha is based on Hallman’s discoveries such as “finding her name in a plantation inventory from 1828” and “discovering her marked gravesite in a remote Virginia forest.” These and other documents confirm Anarcha’s actual life, the multiple ways her name was spelled, and her movement throughout the South. They also confirm that despite these many moves, Sims continued to experiment on Anarcha, including an 1857 surgery. The latter proves that although Sims claimed early on to have cured Anarcha’s vaginal fistula—a hole in the vaginal wall, the result of long labor when she was little more than a child—he had not. Anarcha continued to suffer from the debilities (and constant marginalization) caused by urine and feces leaking constantly into and from the vagina. Her condition worsened with additional pregnancies. These very vivid and specific details, documented by facts, grounded Hallman’s biographical work, but additional information was needed to explore both Anarcha’s life outside of the influence of Sims and the veracity in the carefully constructed (and, at times, fabricated) paper trail that Sims left behind for himself.

As Hallman explained, “Anarcha’s story is told in really a two-fold manner: there is the primary source record of her life, hard facts, and a great deal could be discerned from that. But, second, I took the further step of augmenting her life with additional facts: material drawn from the WPA slave narratives, which were created precisely so that they could be used by historians and creative writers. The result is perhaps something closer to the art of collage—facts that have been speculatively arranged. Again, if the reader is made fully aware of this process, they will accept an artfully arranged history, and we can escape the shortcomings of a tradition that tends to aid and abet the false biographies of figures like J. Marion Sims.”

Hallman’s dual biography then is not just about confirming and expanding Anarcha’s story; it also deconstructs the hagiography of Sims established by Seale Harris’s Woman’s Surgeon (Macmillan, 1950). As Hallman further explained, research discoveries “large and small” prompted him to retell Sims’s life. Among his discoveries were: “Sims did not invent silver suture material;” “Sims did not invent the speculum;” “Sims acted as a spy on behalf of the Confederacy during the Civil War;” and “Sims’s fistula cure was wholly abandoned four years after he proclaimed it.” Hallman’s account also points out Sims’s fraudulent applications to medical school and his admiration of P. T. Barnum—two items that add to the portrayal of the physician’s drive and self-creation. As Hallman summarized, “I certainly felt fired up by the fact that so much of the ‘official’ story of Sims’s life could easily be shown to be utter fiction.”

Hallman, an author of short fiction, as well as five other nonfiction books and numerous essays, holds an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa (and an M.A. from Johns Hopkins University). How did techniques from this creative writing factor into the “speculative” elements of this work? How did they help him to shape the lives of these two characters for readers? Drawing from his past publications and training, he believed that he “could bring something to the story that was both new and necessary.” Using scenes “that were scruples-testing or complex,” such as the lack of acquiring “consent” or the use of anesthesia, Hallman sought to make the characters “felt and lived, rather than documented.” His goal was to put readers in the place of both Sims, the physician, and Anarcha, the victim, during the time these experiments were underway.

Another important choice was in the selection of illustrations, which pepper the pages. These remind readers “that everything in the book comes from a source” while they especially allow non-scholars “to feel the excitement that biographers and historians feel . . . as they pour through archival material.” They add to the feelings of the past while contributing to the account’s veracity. Hallman described their use as similar to “standing before the skeleton of the tyrannosaur at a natural history museum. There, you have the opportunity to behold this creature, experience its presence, feel some echo of its life, though of course it may not be a skeleton at all, but casts compiled from a number of archaeological sites, creatively compiled by archaeologists. My telling of Anarcha’s story . . . is in that vein.”

To keep readers moving along with the two main characters, as their separate life stories proceed, chapters shift back and forth with diverse perspectives, including sometimes those of secondary characters, such as Sims’s colleague Thomas Addis Emmet and journalist Mary Booth. “I opted for a sometimes choppier structure that appeals to the reader’s ingenuity and attentiveness,” Hallman explained. When writing, Hallman noted, he adheres to what Henry James once said: “A writer’s obligation is to ‘be interesting.’”

One of the ways Hallman maintains interest as he moves among characters is through the use of controlling metaphors. “Something that stood out in my early reading was many writers who had employed flamboyant astronomical metaphors to describe Sims, likening his career to a comet streaking across the sky. . . . It was easy to connect this to ‘night of the falling stars’ [November 13, 1833], which I found to be prevalent in the slave narratives compiled by the Federal Writers Project.” (The latter was a key source for his project.) This date also “was Sims’s first day in medical school, and . . . he died exactly 50 years later.” It might seem fictional, “if [it] wasn’t so easy to document. It didn’t hurt that virtually everyone, in this period, was reading metaphors into the actions of the heavens. To that extent—and this would apply to the book’s use of ghosts, monsters, as well—I was employing metaphors proposed by history itself, rather than imposing something of my own onto the story.”

Making this speculative biography distinct from historical fiction and unique among biographies are its front and back matter: An introduction and an afterward refer overtly to contemporary social activism—such as the removal of Sims’s statue from Central Park and contemporary work conducted by humanitarian medical organizations with the women’s fistulae crisis in Africa. Additionally, Hallman’s editor, Retha Powers, encouraged him to write himself into a scene of the discovering of Anarcha’s grave. Then, instead of acknowledgements, there are three pages of “Their Names”: “A complete list of all the formerly enslaved persons whose narratives contributed to the re-creation of Anarcha’s story.” And, tellingly, Hallman’s name is absent from the front cover (although it appears on the title page), an idea the publisher proposed. “The whole point was to center Anarcha’s story,” he explained.

Hallman acknowledged the challenges of writing and of reading this book. “Difficult history tasks us—as human beings—with bearing witness to its darker episodes, and sometimes this means rising to the occasion of narrative strategies that challenge us.” He also said:

There are a few ways to indicate when a creative process has been brought to bear on a body of fact: caveats in a book’s front matter, introductory explanations of methodology, and in-line indications when a described event is inferred rather than documented. Say Anarcha does all three, and my feeling is that when a reader feels “in on it,” when they understand that what they are reading is a kind of thought experiment, a lot more can be included under the umbrella of nonfiction.

As a biographer, I wondered what challenges to Hallman’s work might be voiced by potential readers. For instance, descendants and friends of Sims and Anarcha, or others, might not think a white male should be writing Anarcha’s story. To this idea, Hallman said, he believed he “would be consigning Anarcha to the abyss of the past all over again,” if he had decided not to pursue the project. That decision “would have made me complicit,” he realized. “I would have been assisting Sims in his ongoing control of her story, much in the same way he once controlled her body. I could not abide that.”

Once Hallman located Anarcha’s grave, he also found “descendants of her husband, Lorenzo, who is buried alongside her. They are in support of the book, and we are working together now to ensure that Anarcha’s gravesite is protected.” As he explained in summation, “A chorus of voices have contributed to remembering Anarcha. My hope is that the extensive research that went into finding Anarcha and recreating what can be said about her life earns me a place among that chorus.”

You can learn more about J. C. Hallman here.

Etta Madden is the author of Engaging Italy: American Women’s Utopian Visions and Transnational Networks (SUNY Press, April 2022) and other books and articles about American women writers, American literature, and utopian food and communities in the United States and Italy. Visit her website here.

|

|

|

|

MEMBER INTERVIEW

Six Questions with Susan Goldman Rubin

What’s your current project and at what stage is it?

I’m currently working on a young adult biography of Stephen Sondheim, the composer and lyricist who changed musical theater. I began this project a number of years ago and had the great pleasure of interviewing Sondheim at his home in New York. First, I interviewed some of his collaborators such as his good friend, composer Mary Rodgers, and his longtime orchestrator, Jonathan Tunick, who turned out to be one of my classmates from The High School of Music & Art. I’ve revised and updated an earlier version of the manuscript and am now working on the next draft based on comments from my editor at Calkins Creek/Astra Books for Young Readers. I’m very excited about this book and publishing excerpts from my interview with Sondheim that may never have been heard before.

Who is your favorite biographer or what is your favorite biography?

One of my favorite biographers is Victoria Glendinning. I discovered her writing when I wanted to know more about one of my favorite authors, Elizabeth Bowen. Bowen’s novel The Death of the Heart sits on my nightstand for continual rereading, especially part two. It was almost sacrilegious to not let the novel speak for itself, yet I wanted to find out something about the author’s own life. I was captivated by Glendinning’s storytelling ability, her conversational tone, and brilliant sense of time and place. Her biography of Elizabeth Bowen was marvelous to read in its own right. In fact, her comments relating parts of Bowen’s life to her novels and stories deepened my pleasure. However, it was maddening to find out that Bowen had been teaching at Bryn Mawr here in America at the time I was an English major at Oberlin. I could have made an attempt to meet her, and possibly sit in on one of her classes. Glendinning described Bowen as friendly and accessible, another surprise.

What have been your most satisfying moments as a biographer?

It’s tremendously satisfying to find the rights holder to a photograph from a library collection or archive that I feel I must have as an illustration for my biography. Sometimes the library has no accurate knowledge of where the photo came from and occasionally the picture is misidentified. The search itself can lead to invaluable contacts. For example, when I was doing photo research for my chapter on Chinese American filmmaker Marion Wong, in The Women Who Built Hollywood: 12 Trailblazers In Front of and Behind the Camera, I tried to find photos of her and still frames from her landmark movie, The Curse of Quon Gwon. Although I found images in the book Hollywood Chinese by Arthur Dong, the true rights holder was Marion’s great nephew Gregory Mark Yee and his family. I tracked down Greg in Hawaii and we talked over the phone. His comments added vital information to my chapter—it was his grandmother who starred in the film, and casually turned the almost forgotten reels over to him. Greg realized the value of the remaining film, preserved it, and brought it to the attention of the public. He, in turn, was delighted to introduce his great aunt’s pioneer work to a new generation of readers and filmgoers.

What have been your most frustrating moments as a biographer?

For me, the most frustrating moments are gathering my source notes and citing them correctly in the back matter of the final draft. As I write and choose quotes, it’s like writing a libretto. I look for words everywhere that bring my subject to life, yet make sense for today’s young reader. I use a wide variety of sources—interviews, transcripts of oral interviews, published books, newspaper clippings and, for The Women Who Built Hollywood, articles from movie magazines of the period. For example, I watched clips on YouTube of actress Lillian Gish and film editor Margaret Booth accepting awards, and wrote down the words they spoke that expressed what I wanted the reader to know. One page in any biography I write may include quotes from five different sources, yet they must fit together smoothly.

What person would you most like to write about?

I would like to write about the Jewish artist Chaïm Soutine and his dynamic paintings that came to be known as The School of Paris. I’m developing a draft that I hope will interest an editor in the near future.

What genre, besides biography, do you read for pleasure, and who are some of your favorite writers?

At the end of the working day, I need a story fix and love to read novels and occasionally short stories. As an Anglophile, I’m drawn to the work of British female authors such as Elizabeth Bowen, Tessa Hadley, Elizabeth Taylor, Penelope Lively, and Jane Gardam. And, as a fan of mysteries, I was thrilled to recently read books by English author Susie Steiner. Sadly, Steiner died last year at the age of 51. Of course, I greatly admire the wealth of fiction written by many men, for instance, Ian McEwan. I’m currently caught up in reading his novel Lessons and linger over beautifully composed passages. I’m amazed that I stay with McEwan’s male protagonist as the story goes back and forth in time, a device that usually bothers me. I first read a condensed excerpt of Lessons in The New Yorker and was disturbed yet captivated by the story and never forgot it. The New Yorker is also where I discovered Elizabeth Taylor, then Tessa Hadley, and have gone on to read everything they’ve published.

Susan Goldman Rubin is the author of more than 55 books for young people, including the newly released YA anthology The Women Who Built Hollywood: 12 Trailblazers in Front of and Behind the Camera (Penguin Random House, May 2023). You can learn more about the book here.

|

|

|

|

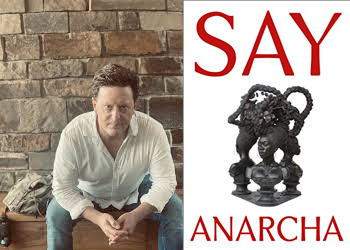

WRITERS AT WORK

Raquel Ramsey

BIO member Raquel Ramsey shared this photo of her home office in Los Angeles. The photo was taken while Ramsey was participating in an interview with the National WWII Museum for Women’s History Month.

|

Would you like photos of your work featured in The Biographer’s Craft? Do you have candids from the 2023 BIO Conference? Submit them here.

|

|

|

|

AMANUENSIS

An Interview with Jennifer Homans

Winner of the 2023 Plutarch Award

(Originally published by Advice to Writers.)

I became a writer by being a shy person and a dancer. I am very internal and have always liked to sit alone in dark theaters watching dance and scribbling thoughts. Or performing, which is also a very private experience, even (or because) it is for a public. Writing is always for me a way of thinking–I don’t know what I am going to “say” before I write it. Dance mattered because, somehow, the direct connection between seeing or moving and the task of describing my own thoughts in the moment, as a thing, but also as an effect on my own being, is something private and natural to me. I see better and feel more when I write it down. I have ideas when I move to music, and often took a pen and paper with me to dance classes. The process was so private that I never imagined I would share my writing, and to this day, I feel oddly surprised when I see my work in print. When I am writing, no one else is there, just me (barely) and the material. In this sense, it is very much like dancing. FULL INTERVIEW

|

|

|

|

BIO PODCAST

Chad Williams

Recently on the BIO Podcast, BIO member Sonja Williams interviewed Chad Williams (no relation), author of The Wounded World: W. E. B. Du Bois and the First World War (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023). You can listen here.

|

|

|

|

KEEP YOUR INFO CURRENT

Making a move or just changed your email? We ask BIO members to keep their contact information up to date, so we and other members know where to find you. Update your information in the Member Area of the BIO website.

|

|

|

MEMBERSHIP UP FOR RENEWAL?

Please respond promptly to your membership renewal notice. As a nonprofit organization, BIO depends on members’ dues to fund our annual conference, the publication of this newsletter, and the other work we do to support biographers around the world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIO BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Steve Paul, President

Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President

Marc Leepson, Treasurer

Kathleen Stone, Secretary

Michael Gately, ex officio

Kai Bird

Heather Clark

Natalie Dykstra

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina

Carla Kaplan

Kitty Kelley

Susan Page

Tamara Payne

Ray A. Shepard

Barbara Lehman Smith

Kathleen Stone

Eric K. Washington

Sonja D. Williams

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Debby Applegate, Chair • Taylor Branch • A’Lelia Bundles • Robert Caro • Ron Chernow • Tim Duggan • John A. Farrell • Caroline Fraser • Irwin Gellman • Michael Holroyd • Peniel Joseph • Hermione Lee • David Levering Lewis • Andrew Lownie • Megan Marshall • John Matteson • Jon Meacham • Candice Millard • James McGrath Morris • Andrew Morton • Arnold Rampersad • Hans Renders • Stacy Schiff • Gayfryd Steinberg • T. J. Stiles • Rachel Swarns • Will Swift • William Taubman • Claire Tomalin

|

|

|

|

|

THE BIOGRAPHER'S CRAFT

Editor

Holly Van Leuven

Consulting Editor

James McGrath Morris

Copy Editor

Margaret Moore Booker

|

|

|

|