Biographer Explores the Life of a Film Pioneer—Her Father

Radha Chadha is a brand consultant as well as a first-time biographer.

If BIO gave an award to the member who ventured the farthest for its annual conference, Radha Chadha would have taken it for 2016. Originally from India, Chadha traveled from her current home in Dubai to Richmond for this year’s event, after being introduced to BIO by TBCNew York correspondent Dona Munker. The path to meeting Munker intersected with Chadha’s effort to write a biography of her father, the documentary filmmaker and producer Jagat Murari.

As Chadha told TBC via email, she was going through her late father’s papers in Pune, a city near Mumbai, when she discovered diaries going back to his days as a film student at USC shortly after World War II. The diaries mentioned a Persian princess named Sattareh Farman Farmaian, whom Murari had met at the school. Farmaian, Chadha learned, had written an autobiography with Dona Munker’s assistance, so Chadha contacted the BIO member, starting a relationship that has been very fruitful for the rookie biographer. Chadha said that Munker “has been amazing—very generous and full of helpful advice that a first-time biographer like me thirsts for. I found the same generous spirit at the BIO conference in Richmond. I am simply delighted to be part of this group.”

What led Chadha to tackle the challenge of writing about her father’s life? Part of it was wanting to tell the story of a key figure in postwar India filmmaking. “He has a fascinating story of achievements that even I didn’t know properly,” Chadha said. “He is a pioneer in the Indian cinema world, both as a documentary filmmaker and a film educator.

Murari directed nearly 50 films, and many of them won national and international awards and were screened at some of the world’s most prestigious film festivals. As an educator, Chadha said, her father was “in a sense…the man who changed Bollywood, who injected a steady stream of professionally trained directors, technicians, and actors into India’s prolific but chaotic film industry from the 1960s onwards.” Murari did that work as the head of the Film & Television Institute of India (FTII), which he created. “Think about it,” Chadha said. “Just a dozen years after India’s independence, in a desperately underdeveloped country, he builds the finest film school in India; it becomes the largest in Asia. His students become the who’s who of Bollywood, as well as the instigators and key players in the New Wave cinema movement that picked up steam in the late 1960s in India.”

Chadha was also drawn to her father’s story because his work in cinema is a part of modern India’s history that has largely gone untold. His documentaries, she said, “tell the story of India’s attempts to develop and unite a fragile nation, they capture a certain innocence or idealism of the times as India tried to ingrain the spirit of democracy in a vast, far-flung, diverse, poor, largely illiterate country.”

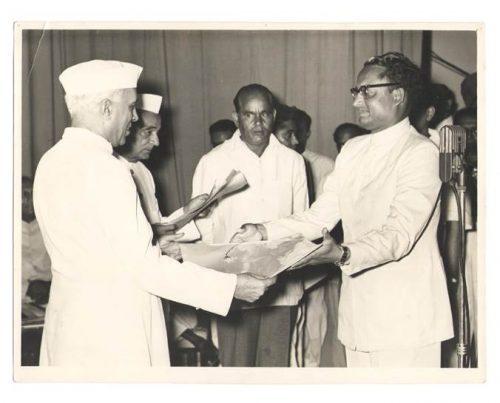

Jagat Murari (right) receives an honor from Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1956.

Adding some spice to the story, it doesn’t hurt that Murari did an internship with Orson Welles while the director was making Macbeth¸ and that he later met world-famous directors as they passed through India. And for a time, Indira Gandhi’s role as the country’s Minister of Information and Broadcasting effectively made her Murari’s boss.

Asked how to balance the desire to be objective while writing about a parent, Chadha called that “the heart of the dilemma I face—how to do your duty as a biographer (by being as objective as possible) while doing your duty as a daughter (by presenting him in the best light possible).” Chadha is turning to her father’s filmmaking as a guide of sorts. Above all, she said, her father was a dramatic storyteller, “and every good story is ultimately a tussle between the forces of good and bad… the forces that propel your character forward and the forces that prevent him from getting where he wants to…. Fortunately, my material has plenty of drama built in—he was strong-willed, he was a visionary, he was in a tearing hurry, he made things happen against formidable odds…. He made enemies along the way, he made mistakes, there were ups, yes, but there were some pretty awful downs. Much as I love him, it would be totally counterproductive to write an I-love-my-daddy puff piece. I just have to get out of the way and tell the story.”

Chadha has some advice and caveats for other biographers thinking of writing about a close relative: “Of course, talking to other people is a great help. But people are not forthcoming about the negative stuff—in fact, one of my surprising learnings is that many elderly people haven’t told me the truth. I had naively imagined that “age equals honesty”—it doesn’t. But if you talk to enough people, you will get to the truth, a few will spill the beans. And every interview, even the sketchy ones, gives you a sense of what might have happened. Soon you begin to notice contradictions, and that leads to many ‘aha’ moments. It is detective work, but so much fun when you figure out someone’s motives. More importantly, it helps you develop a considered viewpoint, and ultimately, that’s what matters. I think the only way to write convincingly is to be convinced.”

Many of the people Chadha hoped to interview had passed away, but even talking to their surviving spouses or children helped. “It has led me to books/articles/speeches (often in languages that have needed translation) that I would not have found without the family’s help. Even better, it has led me to colleagues who are alive. For example, I stumbled upon a 94-year-old man who had studied with my father at USC—they had even shared a room for a short period.”

Chadha also benefited from her father’s being something of a celebrity for most of his career, so newspapers covered his activities. “But again,” she added, “I have learned that they don’t necessarily tell the truth—there are vested interests, there is careless reporting—you have to test the information with your other sources.” Her father was a controversial figure, Chadha said, as some critics accused him of being too enamored of a commercial, Hollywood style of filmmaking when other countries were moving toward the French New Wave approach. As Murari got caught up in the debates, the reporting on him was a “mixed bag.” Overall, Chadha said, trying to remain objective while writing about a famous parent put her on high alert: “You simply try harder. You try to get multiple viewpoints from multiple sources.”

The sources included, of course, Murari’s films, which Chadha said helped her learn who he was as both a filmmaker and a human being. She also studied the films of his students. In the Bollywood vs. New Wave debate, she thinks her father saw value in both approaches. “His aim was to make ‘better cinema’—through professionally trained filmmakers—never mind which side of the fence that cinema came from.”

Today, India has the largest film industry in the world, producing up to 2,000 full-length movies each year. Both splashy Bollywood spectacles and more serious art-house films are shown around the globe. Radha Chadha is still uncovering the role her father played in creating that industry. “It is,” she said, “a story that needs to be told.”