2024 Plutarch Award Longlist Announced

The longlist for the 2024 Plutarch Award has been determined, and you are the first to know. The committee for this year’s prize is composed of Carol Sklenicka (chair), Patricia Albers, Vanda Krefft, William Souder, and Ethelene Whitmire. Sklenicka said of their work, “The 2024 Plutarch Award Committee received some 200 books by first-time and experienced biographers, issued by small and large publishers, on subjects who made their lives in worlds as vastly different as ancient Greece and Silicon Valley. During months of reading and discussions by email and on Zoom, we five jurors looked for books that met the standard set by earlier Plutarch winners for ‘the quality of research, the literary merit of the writing, and the originality and significance of the project.’ We pulled back from books that fill holes in the available research with fiction but welcomed unconventional group subjects and timelines. We admired biographers who could find the sweet spot where facts speak plainly yet powerfully. Each biography on our longlist evinces intellectual curiosity, rigorous research, and a distinct narrative voice that tells a story and wins readers’ trust.”

BIO President Steve Paul added, “We are all grateful for the committee’s obvious care, devotion to quality, and astute thought in handling this assignment.”

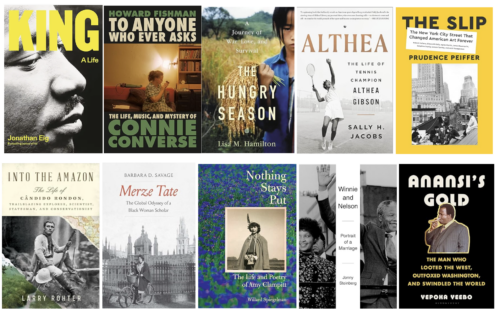

The titles, in alphabetical order by author’s last name, are as follows:

Jonathan Eig, King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

The legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. has been central to American public life since his assassination in 1968, though it is usually remembered as a tableau of brief, grainy film clips and indelible utterances that took place between the spaces in which his actual life unfolded. In this sweeping and humane biography, Jonathan Eig closely examines King’s whole story, including aspects of its private side revealed by recently released FBI wiretaps. Eig pays particular attention to King’s early life in Atlanta, where he became aware of segregation at the age of six, when a white boy he was friends with went off to a different school and they were no longer permitted to play with each other—an event King would later say shaped him for life. Eig also illuminates the tensions within the leadership of the civil rights movement, where not everyone tolerated King’s patience and belief in nonviolence, especially as the imperatives of Black Power became more central to the cause. Eig, a prudent and judicious observer, wisely stays out of the way of his own narrative, letting the events of King’s life speak for themselves. Often, those events threatened his very life. Once, handcuffed during a six-hour nighttime car ride with two hostile white police officers, King could do nothing but wonder what was about to happen to him. “It was a long ride,” King said. “I didn’t know where they were taking me.” Of course, that’s different from knowing where you’re going, which as Eig shows in this fine book, is something King never doubted.

Howard Fishman, To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse (Dutton)

When writer and musician Howard Fishman first heard a recording of Connie Converse, time seemed to stop. Who was she? What became of her? Fishman brings both passion and expertise to bear in trying to answer those questions in this expansive and searching biography of a gifted singer-songwriter who never made it. Fishman argues that, with her twangy guitar and plaintive voice, Converse was a pre-Dylan oddity who wrote folk songs before that was a thing, and skillfully examines her place as a missing link in the evolution of popular music. A high-school valedictorian and college dropout, Converse arrived in New York City in 1944, restless, eccentric, and far ahead of the folk tidal wave she might have ridden to success had her timing been better. Instead, Converse retreated to Michigan where she tried to write a novel, landed a job editing an academic journal, and grappled with depression. Eventually, she told friends she was returning to New York, then got in her car and vanished without a trace. Fishman takes readers along on a tenacious quest to find a ghost and understand what happened to her.

Lisa M. Hamilton, The Hungry Season: A Journey of War, Love, and Survival (Little, Brown and Company)

Photographer and agriculture reporter Lisa M. Hamilton took an unexpected leap into biography when she met Ia Moua on her irrigated farm plot near Fresno, California. Hamilton needed an angle for a book about rice that she’d already sold to a publisher. Moua, a Laotian Hmong who spoke no English and could not read any language but had a story to tell, needed a listener. Thus began an arduous, seven-year collaboration among Moua, Hamilton, and interpreter Lor Xiong. Born in 1964, Moua survived years in a Thai refugee camp where she had eight children before immigrating to Fresno in 1993. In the parched, unfamiliar climate of the San Joaquin Valley, Moua learned to grow a strain of rice traditionally prepared by Hmong people to celebrate their new year. Hamilton supports her meticulous reporting with immersion in Hmong culture (she accompanied Moua and her children to Laos three times) and research into Southeast Asian agricultural and political history. At the center of this intimate biography, Ia Moua comes alive, a personification of the qualities of adaptability and resilience that Hamilton perceived in rice. A model of nuanced biographical writing that transforms an unknown subject into an extraordinary one, The Hungry Season is compelling, lyrical, and humane.

Sally H. Jacobs, Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson (St. Martin’s Press)

Althea Gibson was an astonishing tennis player and all-around athlete who brought her competitive drive to every sport she played. Standing nearly six feet tall, Gibson was the first Black woman permitted to play in the U.S. Tennis Association, won the U.S. Open and Wimbledon championships by the time she reached 30, and was named Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press for 1957 and 1958. But breaking color barriers did not pay the bills, and Gibson struggled financially for much of her life. Gibson’s athletic career began when, after making her name as a tough fighter against both girls and boys in her Harlem neighborhood, she won the New York citywide pingpong championship and was adopted and coached by two Black Southern doctors. She flourished as a competitive amateur tennis player, graduated from college, and became the world’s top-ranked player for two years in a row. She worked as a professor, traveled for the U.S. State Department, played exhibition games with the Harlem Globetrotters, made a record album, and became the first Black woman in the Ladies Professional Golf Association. Sally H. Jacobs narrates Gibson’s personal battles and triumphs with appreciation for her subject’s strong personality, including her resistance to being defined as a representative of her race, and surrounds Gibson’s story with a rich sense of place, social and political context, and class distinctions. Gibson’s two memoirs and more than a hundred interviews conducted by the author endow this biography with a familiarity often missing from stories about famous firsts.

Prudence Peiffer, The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever (Harper)

Prudence Peiffer’s riveting The Slip follows the lives of seven artists who, in the mid-1950s, converged on a warren of derelict sailmaking warehouses on lower Manhattan’s Coenties Slip. In that obscure corner of the city, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Lenore Tawney, and Jack Youngerman created paintings, sculptures, and weavings that sent American art in new directions, Peiffer argues, while Delphine Seyrig launched an inspired acting career. This astutely researched and richly anecdotal group biography is steeped in a strong sense of place. It weaves together a history of the waterfront, tales of its raucous denizens, and explorations of their brilliant art. Eclectic though their achievements were, all were nourished by the material conditions of Coenties Slip and the collective solitude it provided.

Larry Rohter, Into the Amazon: The Life of Cândido Rondon, Trailblazing Explorer, Scientist, Statesman, and Conservationist (W. W. Norton & Company)

To the extent that Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon is known in this country, it is as Theodore Roosevelt’s co-leader of the harrowing 1914 expedition on the River of Doubt, in a remote section of the sprawling Amazon jungle. Larry Rohter’s stirring biography fills in the rest of Rondon’s remarkable story. Rohter writes that no other tropical explorer rivals Rondon in miles traveled, mountain ranges traversed, hostile and uncontacted peoples encountered, and technological feats accomplished. Trained as a scientist and engineer, Rondon oversaw the construction of thousands of miles of telegraph lines deep into the Brazilian jungle, eventually across the far reaches of the Amazon basin and into Bolivia and Peru. Roosevelt declared Rondon’s telegraph project an achievement equal to the Panama Canal. Rondon, who was of Indigenous, European, and African descent, was also an ethnographer and fierce defender of the rights of the Indigenous people living in the most inaccessible parts of the Amazon. Rohter argues that Rondon’s reputation would be far greater if not for racism and resistance to his belief in the humanity of all people. Engaging and uplifting, the book is biography at its best. And no surprise. As Rohter reveals—in a passage casual readers might skim, but which will spark envy among biographers—wherever he went in his long, meaningful life, Cândido Rondon kept a journal.

Barbara D. Savage, Merze Tate: The Global Odyssey of a Black Woman Scholar (Yale University Press)

Barbara Savage’s biography of the audacious diplomatic historian Merze Tate, the first Black woman to earn a degree from Oxford and the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in Government from Harvard, forcefully shows that the pleasure of intellectual work can be—and in Tate’s case, was—the motivating desire in a woman’s life. Born in white, rural central Michigan in 1927, Tate dazzled high-school oratory judges with a demand for racial equality. Surmounting barriers through college and beyond, the intrepid Tate never took no for an answer. Solo travel, first to Europe, then to India as an early Fulbright scholar, and later to Africa, fostered Tate’s antiracist geopolitics. As a professor and prolific scholar at Howard University, Tate defied the expected research fields for Black historians by focusing on post-World War II international relations, insisting that American power be held to account and presciently arguing that infrastructure investments and weapons production were a form of neocolonialism. Savage, an academic historian who describes herself as a “reluctant biographer,” spent ten years immersing herself in a new genre and writing this book. Lifting Tate’s life story from a richly layered palimpsest of archival materials, Savage conveys the intense commitment and joy of a life devoted to learning, thinking, and teaching.

Willard Spiegelman, Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt

(Alfred A. Knopf)

A sumptuous and compassionate biography of the brilliant poet Amy Clampitt, Nothing Stays Put follows Clampitt from her humble Iowa farm beginnings to her days of acclaim at the epicenter of New York’s literary scene. Clampitt’s genius remained unseen for decades—until a colleague submitted a handful of her poems to the New Yorker without telling her. The magazine’s acceptance of one of them launched a career that rose like a rocket. At 58, Clampitt became, in Spiegelman’s words, “the country’s oldest young poet.” An English professor turned critic and essayist, Spiegelman writes with grace and a disarmingly fluid sense of chronology, pulling together the disparate threads of Clampitt’s life, including her disillusionment with religion (she was raised a Quaker) and her political activism. He is also an expert and generous interpreter of Clampitt’s sometimes complex and always exquisite poetry.

Jonny Steinberg, Winnie and Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage (Alfred A. Knopf)

South African novelist J. M. Coetzee rightly calls this dual biography of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Nelson Mandela “a massive essay in political biography.” Steinberg’s book relies on a voluminous, recently uncovered file stolen by the apartheid regime’s last minister of justice and prisons when he left office. With the insights provided by that archive, Steinberg fulfills the promise of his title: this is truly a biography of a marriage. The Mandelas lived together just four years after marrying in 1958; they were not allowed to touch each other for years after Nelson was imprisoned for treason. During that time, both fought to end apartheid and to burnish the myth of their beautiful partnership despite growing ideological differences. They divorced in 1996 while Nelson was serving as South Africa’s first post-apartheid president. Steinberg deftly arranges complex historical information, yet what sets this book apart as a biography is his tone. “A biographer ought to be wary of the idea that any document reveals his subject’s essence,” he writes after quoting a particularly raw letter by Winnie. In his final chapter, Steinberg recounts an occasion when he, a white college student, shook Nelson Mandela’s hand. Maybe that incident explains the author’s fascination with his subjects; more importantly, his analysis of the episode displays his impartiality and wisdom. Throughout this powerful biography, Steinberg imbues a painful, sometimes lurid story with the love and respect its subjects deserve.

Yepoka Yeebo, Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World (Bloomsbury)

In a captivating, genre-bending debut, Yepoka Yeebo reconstructs the strange life of John Ackah Blay-Miezah, a big, cigar-chomping flim-flam man from Ghana who masterminded one of the largest, longest-running con jobs the world has ever seen. Yeebo sets the stage in the tumultuous early days of independence from British rule when most of Ghana’s considerable wealth was still held in London. When Ghana asked for its money, much of it had disappeared in bad investments. The scandal lodged in Blay-Miezah’s brain, where it morphed over time into a bold plan glued together with criminal intent. For years, Blay-Miezah lived lavishly and outwitted his investors, Ghanaian governments, Swiss bankers, British businessmen, and the FBI. To research this brilliant study of human duplicity and greed, Yeebo sought obscure and far-flung sources. She found people willing to talk and documents that had survived war, fire, and rampages. Yeebo skillfully pulls back Blay-Miezah’s curtain of lies and fake identities to reveal how he charmed his victims out of millions. Wry, penetrating, and unfailingly entertaining, the book sits at the intersection of biography, history, and investigative journalism.