Using the Art and Craft of Research: Conducting and Organizing Research on Four Generations of Morgenthaus

By Andrew Meier (as told to Holly Van Leuven)

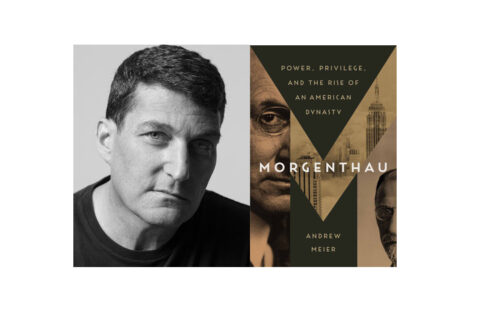

Editor’s Note: In October, BIO member Andrew Meier published Morgenthau: Power, Privilege, and the Rise of an American Dynasty (Random House, 2022). The work, which took over a decade to complete, is more than one thousand pages long, 75 of which are endnotes. To complete the book, Meier conducted 350 formal interviews and spoke to an additional 150 sources. He spoke to one of his main sources, the late Robert Morgenthau, who was the longtime district attorney for New York County, for hundreds of hours. All of this suggested that Meier would be an excellent person to talk to about the art and craft of research. Although he was still feeling “half-numb” from the aftermath of launching such a work into the world, he graciously spoke to me about the “ins and outs” of his research process, particularly with regards to keeping research organized. The conversation left me energized to go hit the archives with some new tools; upon reading his ideas, I believe others may feel similarly.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

I love writing, as painful as it is. I can write for 10 or more hours at a stretch. As any editor I’ve ever worked with will amply attest, I write long and the words come fast, and then I cut mercilessly. But in the aftermath and aftershock of the publication of Morgenthau, I can readily say that research motivates me first and foremost, because it is detective work in some ways. It is the organization of my madness. It’s not anarchic, but it is organic. I do nonfiction investigation. I am not a trained historian. I am not really a trained biographer. I wouldn’t even say that I’ve read more biographies than nonfiction narratives. But my guiding tenet is: the initial idea needs to pursue you, and then you need to pursue it. Everything that derives from that initial idea is pursuit.

When I first thought about this book, I framed it in my mind. I didn’t want to do a book just on Robert Morgenthau, the district attorney from New York. Other people will do that, other amazing biographers were interested in it. The four or five publishers I got down to didn’t want that; they wanted the long arm of history. Four generations of Morgenthaus are what I researched.

I thought: What are the big themes across these four generations? Obviously, it’s an immigrant story, it’s the making of New York City, it’s the birth of Progressivism in America. It encompasses the three most important, pivotal presidencies of the 20th century—Wilson, Roosevelt, and Kennedy. It’s the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust, the New Deal, and the last 50 years of crime and punishment in New York and across the country. How to manage it all?

This is my “managing insanity” ledger: I started several documents, Word files. I try to keep everything in paper and digitally. But these four core documents become the essentials:

- The table of contents. Even from the beginning, those big, broad themes I just sketched out are in the TOC. They may be chrono-linear, or they may not be.

- A source list of contacts who are alive, hopefully.

- The bibliography, aka sources who are dead, which are archival, published, or unpublished.

- The chronology: one of the few pro tips I ever got was chronology is your friend.

I update the documents even after publication—I’m still updating all four of those. The chronology is 300 pages, the bibliography more than 200 pages, the contacts a couple hundred pages (although many have now left us), and the TOC is about 40 pages.

I have a syndrome of seeing stories everywhere, most of which I can’t pursue and write. To organize myself, I have to be orthodox on those four documents. I have boxes of hard copies of the source material. I have binders of primary source material—archival or unpublished. I have those color-coded. I print it all out, lest there be a digital disaster. And I am constantly backing up and saving.

In an ideal world, a far more organized person would actually integrate those four documents so that your table of contents would have all those sources—primary, secondary, tertiary—linked to that table of contents, indicating things like: What source came from an interview? What source was a document from the library? That would have saved me months, if not years. But I just hit pause and I write. I always vow that for the next book I’m going to do just that.

Everyone needs to find their own way and then be consistent, so that when you do get lost, you can find your way back to the materials that you need. There’s no greater thrill—says the geek in me—than finding something I need that I last saw seven years ago.

This is really the craft of research, not the art of research. There is a kind of dance of research that’s organic. Once you’ve set the course, you have to be open to the muses of history, or Clio, and she will speak to you, and often when you least expect it—when you don’t even realize it, you’re dumb to it, you’re blind to it. I think “that can’t be . . . that doesn’t make sense . . . wow, that’s interesting,” and then I go home and sleep and let the air into it. I come back to the document and it all makes sense. This is why many people keep a second notebook, not just the notes on what they are researching but the impressions of what they just saw.

I log those “it can’t be” moments of discovery because I’m obsessive. Sometimes those moments of discovery really are fundamental and change the narrative. They can make you pivot or do a U-turn. That’s the inconvenience of fact. I wish I could be a novelist, or maybe I don’t, but nonfiction is about finding and being confronted with what you know to be true and then interpreting and sorting it all out.

I’m writing notes as well, not just after each visit to the archives, but also at the end of each day about what I learned, what questions got answered, what new questions came, what was this particular day’s harvest or row—research is like planting in a huge field—what did this row present, and what other sources should I now go looking for? And, what was surprising, what was already known, what was reinforced? It’s the only way you can go to sleep at night. And I also give myself a starter for the next day—the literal box and folder, but also a research question, like: What was that speech his wife gave upstate? But it’s a process of slow accretion. I subscribe to the Robert Caro school of thought—time equals truth.

One of the very first things I did in terms of principle research is go online and look at archival databases—public, private, state, university, international. I think I counted more than 100 archives. I try to map the most expansive universe of potential material. I search under various spellings. The OCR [Optical Character Recognition, the process that converts an image of text into a machine-readable text format] gets better and better and better. So that gave me the most expansive universe of archival material. Then you’re not throwing a dart, you’re trying to figure out what is most likely to bear fruit. But it’s a needle in a haystack. But I also, at the same time, as a journalist (for I don’t know how many years, a couple of decades), I would go to the live sources. I would go to the oldest people, in their 90s, for their recollections and documents. Never leave an interview without saying: “Who else should I talk to?” Always ask: “Do you have letters, do you have photographs?” Sometimes there’s even film, video, audio. You may hear, “I’ve got old tapes but I don’t know how to play them.” That all accretes very, very quickly. I start looking at concentric circles. Not just living sources who were participants, but also living historians, and I sought out historians who knew or worked with the Morgenthaus—such as John Morton Blum at Yale. I went up to see him. He was retired, but he was in phenomenal shape. He spent years with the secretary of the treasury [Henry Morgenthau Jr.]. He was hired to turn the 900 volumes of the Morgenthau diaries into three published volumes. Over the course of many hours, he said, “You are blessed, because this is what you have to do”—he gave me the Greatest Hits of the Morgenthaus, his version—“This is what you have to do in terms of the secretary of the treasury and FDR, but you can also do what I couldn’t do because I was hamstrung—he [Morgenthau Jr.] didn’t want me to do anything about his sister or his family, nothing personal—he made him tear up those chapters. He didn’t want me to touch antisemitism in the family at all.” He also said the New Deal is a bonanza for a biographer for a couple reasons: the participants all kept diaries—Ickes, Wallace, Stimson, and so on. And also, these are diaries they didn’t ever want to see the light of day. They are pretty unvarnished, especially those three. They offered me an honest look at what they thought of Morgenthau and FDR.

After you seek out those historians and researchers who came before you and primary sources, getting those views and clues, then you go to the archives. It pains me to say: many of those diaries are digitized and online now. I didn’t have that when I was researching. When I pull a paragraph from, say, 1934, I create a file with my notes on it, but I will also try to capture the original document both digitally and printed. Repositories like the Library of Congress, Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, or any of the big commercial databases allow you to capture a digital image but they don’t necessarily preserve the citation or the provenance. So, I developed a habit of writing down the reference on the verso of every single image and page of material. In so doing, I would never have the nightmare of wondering where an incredible quote came from, because losing the reference point for it renders it almost unusable. I call those the “breadcrumbs.”

That’s another whole essential rule of the craft—that’s not the art. On the one hand you’re trying to be absolutely methodical in marking and organizing, in being able to retrace and use, but in the art of research, you have to be completely open to the dance or the spirit or something magical, a higher force. It sometimes feels like a very strange higher force dragging me along, like I’m not doing it. With Morgenthau, that sensation was much less and more infrequent, than it has been with other projects.

You can find things too early in the research process, before you can fully understand them. It could be a photograph or a letter or a document. If you find it at the right time, or if you’re organized and can come back to it, you can understand it. But ultimately biography is the art of subtraction. From principal research, the next four or five years is weeding out the research.

I’m staring at a room full of banker’s boxes and then probably 25 binders full of those printed original documents. I can’t even tell you what percentage of those documents are actually in the book. They are in the bibliography, in the sense that they informed my thinking. “You’ve committed the sin of overdocumentation,” my copyeditor said. I do that on purpose for the people who come after me, the breadcrumbs again, this time left for others.

Learn more about Andrew Meier at his website.