Exploring Speculative Biography Through J. C. Hallman’s ‘Say Anarcha’

by Etta Madden

Editor’s Note: Speculative biography combines the traditional aspects of biography with fiction-writing techniques that allow writers to flush out familiar characters in unfamiliar ways, or to portray little-known subjects with the depth that history—for a variety of reasons—has not been able to afford them otherwise. BIO member Etta Madden interviewed J.C. Hallman, author of the forthcoming Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health (Macmillan, June 2023) to explore this increasingly popular subgenre of biography.

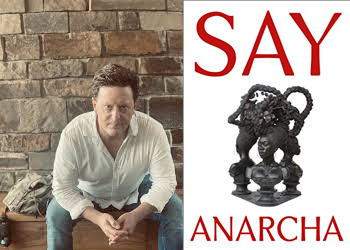

In April 2018, a statue of J. Marion Sims, the controversial “Father of Gynecology” and founder of the New York Woman’s Hospital, was removed from Central Park in protest of the physician’s numerous experiments on enslaved women. Two years earlier, protesters of the statue and Sims’s work had begun chanting: “Say her name! Anarcha!”—the name given to the woman who, beginning in 1846, endured more than 30 “experiments” under the gynecologist’s hands. In June, Henry Holt releases J. C. Hallman’s Say Anarcha: A Young Woman, a Devious Surgeon, and the Harrowing Birth of Modern Women’s Health, a dual biography that expands what we know about Sims and this female subject. Hallman, a former Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow, recently responded to questions about his writing of this book for The Biographer’s Craft, an appropriate subject for the newsletter given that it falls into the subgenre of speculative biography.

Similar to Tiya Alicia Miles’s All That She Carried: The Story of Ashley’s Sack (Random House, 2021), Hallman’s narrative is built upon years of extensive research. But—as with the story of Ashley as explored by Miles—there are elements included of both Anarcha’s and Sims’s stories that are not documented. According to Hallman, those gaps can only be filled by speculation, based on the evidence which does exist.

Say Anarcha is based on Hallman’s discoveries such as “finding her name in a plantation inventory from 1828” and “discovering her marked gravesite in a remote Virginia forest.” These and other documents confirm Anarcha’s actual life, the multiple ways her name was spelled, and her movement throughout the South. They also confirm that despite these many moves, Sims continued to experiment on Anarcha, including an 1857 surgery. The latter proves that although Sims claimed early on to have cured Anarcha’s vaginal fistula—a hole in the vaginal wall, the result of long labor when she was little more than a child—he had not. Anarcha continued to suffer from the debilities (and constant marginalization) caused by urine and feces leaking constantly into and from the vagina. Her condition worsened with additional pregnancies. These very vivid and specific details, documented by facts, grounded Hallman’s biographical work, but additional information was needed to explore both Anarcha’s life outside of the influence of Sims and the veracity in the carefully constructed (and, at times, fabricated) paper trail that Sims left behind for himself.

As Hallman explained, “Anarcha’s story is told in really a two-fold manner: there is the primary source record of her life, hard facts, and a great deal could be discerned from that. But, second, I took the further step of augmenting her life with additional facts: material drawn from the WPA slave narratives, which were created precisely so that they could be used by historians and creative writers. The result is perhaps something closer to the art of collage—facts that have been speculatively arranged. Again, if the reader is made fully aware of this process, they will accept an artfully arranged history, and we can escape the shortcomings of a tradition that tends to aid and abet the false biographies of figures like J. Marion Sims.”

Hallman’s dual biography then is not just about confirming and expanding Anarcha’s story; it also deconstructs the hagiography of Sims established by Seale Harris’s Woman’s Surgeon (Macmillan, 1950). As Hallman further explained, research discoveries “large and small” prompted him to retell Sims’s life. Among his discoveries were: “Sims did not invent silver suture material;” “Sims did not invent the speculum;” “Sims acted as a spy on behalf of the Confederacy during the Civil War;” and “Sims’s fistula cure was wholly abandoned four years after he proclaimed it.” Hallman’s account also points out Sims’s fraudulent applications to medical school and his admiration of P. T. Barnum—two items that add to the portrayal of the physician’s drive and self-creation. As Hallman summarized, “I certainly felt fired up by the fact that so much of the ‘official’ story of Sims’s life could easily be shown to be utter fiction.”

Hallman, an author of short fiction, as well as five other nonfiction books and numerous essays, holds an M.F.A. from the University of Iowa (and an M.A. from Johns Hopkins University). How did techniques from this creative writing factor into the “speculative” elements of this work? How did they help him to shape the lives of these two characters for readers? Drawing from his past publications and training, he believed that he “could bring something to the story that was both new and necessary.” Using scenes “that were scruples-testing or complex,” such as the lack of acquiring “consent” or the use of anesthesia, Hallman sought to make the characters “felt and lived, rather than documented.” His goal was to put readers in the place of both Sims, the physician, and Anarcha, the victim, during the time these experiments were underway.

Another important choice was in the selection of illustrations, which pepper the pages. These remind readers “that everything in the book comes from a source” while they especially allow non-scholars “to feel the excitement that biographers and historians feel . . . as they pour through archival material.” They add to the feelings of the past while contributing to the account’s veracity. Hallman described their use as similar to “standing before the skeleton of the tyrannosaur at a natural history museum. There, you have the opportunity to behold this creature, experience its presence, feel some echo of its life, though of course it may not be a skeleton at all, but casts compiled from a number of archaeological sites, creatively compiled by archaeologists. My telling of Anarcha’s story . . . is in that vein.”

To keep readers moving along with the two main characters, as their separate life stories proceed, chapters shift back and forth with diverse perspectives, including sometimes those of secondary characters, such as Sims’s colleague Thomas Addis Emmet and journalist Mary Booth. “I opted for a sometimes choppier structure that appeals to the reader’s ingenuity and attentiveness,” Hallman explained. When writing, Hallman noted, he adheres to what Henry James once said: “A writer’s obligation is to ‘be interesting.’”

One of the ways Hallman maintains interest as he moves among characters is through the use of controlling metaphors. “Something that stood out in my early reading was many writers who had employed flamboyant astronomical metaphors to describe Sims, likening his career to a comet streaking across the sky. . . . It was easy to connect this to ‘night of the falling stars’ [November 13, 1833], which I found to be prevalent in the slave narratives compiled by the Federal Writers Project.” (The latter was a key source for his project.) This date also “was Sims’s first day in medical school, and . . . he died exactly 50 years later.” It might seem fictional, “if [it] wasn’t so easy to document. It didn’t hurt that virtually everyone, in this period, was reading metaphors into the actions of the heavens. To that extent—and this would apply to the book’s use of ghosts, monsters, as well—I was employing metaphors proposed by history itself, rather than imposing something of my own onto the story.”

Making this speculative biography distinct from historical fiction and unique among biographies are its front and back matter: An introduction and an afterward refer overtly to contemporary social activism—such as the removal of Sims’s statue from Central Park and contemporary work conducted by humanitarian medical organizations with the women’s fistulae crisis in Africa. Additionally, Hallman’s editor, Retha Powers, encouraged him to write himself into a scene of the discovering of Anarcha’s grave. Then, instead of acknowledgements, there are three pages of “Their Names”: “A complete list of all the formerly enslaved persons whose narratives contributed to the re-creation of Anarcha’s story.” And, tellingly, Hallman’s name is absent from the front cover (although it appears on the title page), an idea the publisher proposed. “The whole point was to center Anarcha’s story,” he explained.

Hallman acknowledged the challenges of writing and of reading this book. “Difficult history tasks us—as human beings—with bearing witness to its darker episodes, and sometimes this means rising to the occasion of narrative strategies that challenge us.” He also said:

There are a few ways to indicate when a creative process has been brought to bear on a body of fact: caveats in a book’s front matter, introductory explanations of methodology, and in-line indications when a described event is inferred rather than documented. Say Anarcha does all three, and my feeling is that when a reader feels “in on it,” when they understand that what they are reading is a kind of thought experiment, a lot more can be included under the umbrella of nonfiction.

As a biographer, I wondered what challenges to Hallman’s work might be voiced by potential readers. For instance, descendants and friends of Sims and Anarcha, or others, might not think a white male should be writing Anarcha’s story. To this idea, Hallman said, he believed he “would be consigning Anarcha to the abyss of the past all over again,” if he had decided not to pursue the project. That decision “would have made me complicit,” he realized. “I would have been assisting Sims in his ongoing control of her story, much in the same way he once controlled her body. I could not abide that.”

Once Hallman located Anarcha’s grave, he also found “descendants of her husband, Lorenzo, who is buried alongside her. They are in support of the book, and we are working together now to ensure that Anarcha’s gravesite is protected.” As he explained in summation, “A chorus of voices have contributed to remembering Anarcha. My hope is that the extensive research that went into finding Anarcha and recreating what can be said about her life earns me a place among that chorus.”

You can learn more about J. C. Hallman here.

Etta Madden is the author of Engaging Italy: American Women’s Utopian Visions and Transnational Networks (SUNY Press, April 2022) and other books and articles about American women writers, American literature, and utopian food and communities in the United States and Italy. Visit her website here.