Group Biography

Both Daisy Hay and David Hajdu saw the importance of relationships in the lives of creative subjects.

Moderator Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina began the panel by noting that she had gone from writing about a single subject to doing a group biography. She then proceeded to ask the panel about their experiences going from one type to the other, and in so doing “what the challenges, and joys, and problems were.”

Responding first was David Hajdu, whose books include a biography of songwriter Billy Strayhorn and the group biography Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña and Richard Fariña. He said that even though Strayhorn was a single subject, there was a group element to it, given Strayhorn’s collaborations with other musicians, most notably Duke Ellington. That made Hajdu “acutely aware of how collaborative creative lives are,” which led him to explore how relationships between people inform art in Positively 4th Street.

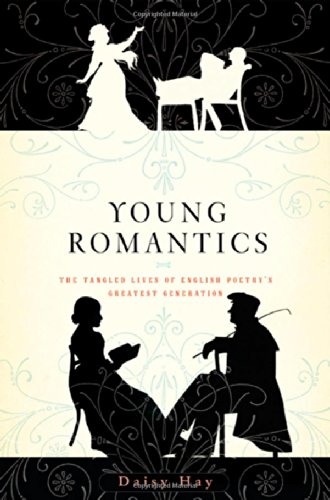

Daisy Hay echoed Hajdu’s observation of the importance of relationships for creative people. Hay, whose books include Young Romantics: The Shelleys, Byron, and Other Tangled Lives, said “literary creativity is never a single person sitting in a room.” She also said that with a group biography, the biographer’s hand is very evident, based on what she chooses to include and who becomes part of the “group.” That control exists to a degree with a single subject as well, she said, but Hay thinks it’s stronger with a group work, because with a single subject “there is a kind of framework of a life to follow.”

For Andrew Meier, it was something of an arbitrary decision to focus on a single subject, Isaiah Oggins, in his first biography, The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin’s Secret Service. He had done a lot of research on his subject’s wife, who was also a spy for the Soviets, and the book, he said, “is really a family biography.”

Gerzina asked the panelists to explore the difference between writing about living or recently living subjects and on those for whom biographers need to rely more on archival material. Meier thought dealing with a living subject (such as Robert Morgenthau and his family) would be easier than spending years in the archives—but “boy, was I wrong,” he said. Living sources and stakeholders contradict each other and know the biographer will be subjective in choosing what to include. Hajdu pointed out a different kind of problem: the written, historical record of Strayhorn’s life did not match the facts, so Hajdu had to rely on interviews with people who knew him.

One challenge of writing a group biography, Hay said, is not to let one strong character “suck the oxygen out of the story.” She found Shelley to be that kind of figure and felt a sense of relief when he died, so she could open up the story to the other subjects. She said biographers should also resist the urge to assign roles to the subjects, to paint one or more as villains, and instead get at “the complexity with which people live their lives, and no one lives their lives in a role like that.”

The panelists talked a bit about the difference between a group biography and a collective biography. For Hajdu, in Positively 4th Street, he definitely saw his subjects as a group—he was not simply taking four separate biographies and “shuffling them together like cards” or creating a collage. He ended up with the relation between the two sisters, Joan Baez and Mimi Baez Fariña, forming the spine of the story. Hay noted that her forthcoming Dinner With Joseph Johnson is a collective biography, as she documents the ties several dozen people had with her titular subject and with each other. She has tried to “look for moments . . . of magnetism between people” and what they said about changes in England during the late-18th century.

Gerzina asked about the challenges of bringing “lesser” figures into the group portrait, especially women who are sometimes left out of the historical records. Meier thought this was particularly relevant when researching his Morgenthau book, which he thought would be male-dominated, but he wanted to know up front: “What about the women?” He found little in the archives about the Morgenthau women, and he said that women are, at times, deliberately erased from the historical record (though the women he interviewed proved to be valuable sources). Hay noted a similar archival hole when researching Mary Anne Disraeli for her book Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli: A Strange Romance. Mary Anne kept everything her husband wrote (and bits of his hair from his haircuts), but no one did the same for her. Hay decided she needed to note the “silences” in the historical record “but not necessarily impose my own voice.”