Book Review – Life as Art: The Biographical Writing of Hazel Rowley

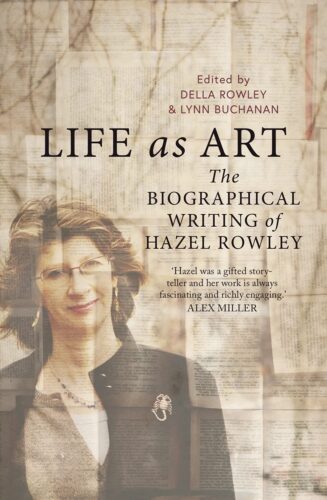

Life as Art: The Biographical Writing of Hazel Rowley

Edited by Della Rowley and Lynn Buchanan

256 pp., Melbourne University Publishing, $34.99

By Carl Rollyson

The range of Hazel Rowley’s biographical subjects—Christina Stead, Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Richard Wright, and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt—may seem eclectic, but her books share a common purpose, which is often the mission of biography: to rehabilitate and reclaim, as she passionately reveals in the essays collected in this volume.

The range of Hazel Rowley’s biographical subjects—Christina Stead, Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Richard Wright, and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt—may seem eclectic, but her books share a common purpose, which is often the mission of biography: to rehabilitate and reclaim, as she passionately reveals in the essays collected in this volume.

Christina Stead, greatly admired by her fellow writers, fell into obscurity in the second half of her career, even though her work, in Rowley’s estimation, suffered no falling off in quantity or quality. Only a biography, she demonstrates, could discover the full significance of Stead’s work, which had been tampered with by publishers and distorted by critics. Similarly, Richard Wright suffered from misconceptions about his decision to leave the United States and live in France, so that he was treated as a writer who had run away rather than as a creative spirit who had saved himself and brought to the second half of his career a profound understanding of world events. Publishers truncated his work and critics, Black and white alike, acted as though going into exile had disqualified Wright from consideration as a major writer when other writers such as Joyce and Nabokov did not suffer such condemnation.

But Rowley is concerned with more than the work of writers. She explored the humanity of Sartre and de Beauvoir that has often been suffocated in critical debates about their politics. Rowley argues that this couple exposed their weak and dark sides with the most ruthless kind of honesty, which their literary executors have tried to stifle by impeding the work of biographers for whom that couple opened their lives.

The pairing of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt was never, in Rowley’s estimation, simply a marriage of convenience. Their personal and political lives were indissoluble, which is what she shows not only in her biography but in essays in this book that dispatch readings of the marriage as merely an expedient alliance. Like her treatment of Sartre and de Beauvoir, Rowley regards the couple as forming a union of sensibilities that could not have thrived—or not thrived as well—as individuals apart from one another. In both pairings, the males and females gave one another a freedom to develop, even when that meant, in conventional terms, that the men and women were not “faithful.” In Rowley’s lexicon, being faithful is more [a] matter of reciprocation, a sharing of values and objectives and not, in any sense, a subordination of one self to another. Of course, all four had their flaws and were not always honest, as Rowley knows quite well, but in following the arc of their lives, she exemplifies that other key commitment of biography: redemption, to show why these lives together were worth it.

But this book is not just about Rowley’s take on her subjects. She exposes her own doubts and frustrations. Could she, as a white woman from Australia, possibly understand an African American writer? She convinced those she interviewed—even the haughty French—with her knowledge and persistence, but she convinces us by showing how misguided much of the Black critics’ interpretations of Wright’s life and work could be. Color, in other words, cannot be dispositive. Biography is about much more than where you come from or what race or sex you happen to belong to. So a combination of factors—a male African American in France and his white Australian female biographer—make for an illuminating, iconoclastic pairing, especially since Wright first came to Rowley’s attention in France, when she was researching the lives of de Beauvoir and Sartre. Biography is about that kind of serendipity and intersection of lives.

I reviewed one of Hazel Rowley’s books, Franklin and Eleanor: An Extraordinary Marriage (2010), and I called it “magnificent.” The same can be said for this collection of essays that are so honest, so penetrating, so beautifully balanced between the biographer and her subjects.