|

February 2024 | Volume 18 | Number 12

|

FROM THE EDITOR

This has really been my Walter Mitty month. Or maybe my Charlie Brown month. Possibly my Mr. Hulot month. No, definitely my Mea Culpa month. What do I mean? It all began on January 31st, when a heroic editorial push by BIO colleagues enabled me to get the long list for the Plutarch Award in the newsletter at the last possible minute. All was looking good, until a mistake I alone made at the very end of the production process meant that the Plutarch Committee chair and members names went out as “Carol Sklenica,” “Vanda Kreffy,” and “William Soulder.” If you wanted a newsletter with those kinds of mistakes, you’d let AI write it!

Fortunately, the errors were corrected before the announcement went beyond this newsletter, and since BIO members are likely very well aware of Carol Sklenicka, Vanda Krefft, and William Souder, most of you probably (thankfully) saw through the gaffe for the goof that it was. Nonetheless, I extend my apologies to the committee members and to all those who read newsletters so thoughtfully.

Just a couple days later began a long period of me vs. winter illnesses and, extending my run of the above, an error slipped into this month’s Insider. (I will save that correction for that publication.) But I am feeling better and am back in the desk chair, somehow it is still February, and there is time for this issue of TBC to reach you. Here’s hoping I leave my blunders in this month (but not this newsletter!).

Enjoy!

Holly

|

|

|

|

PREVIEW

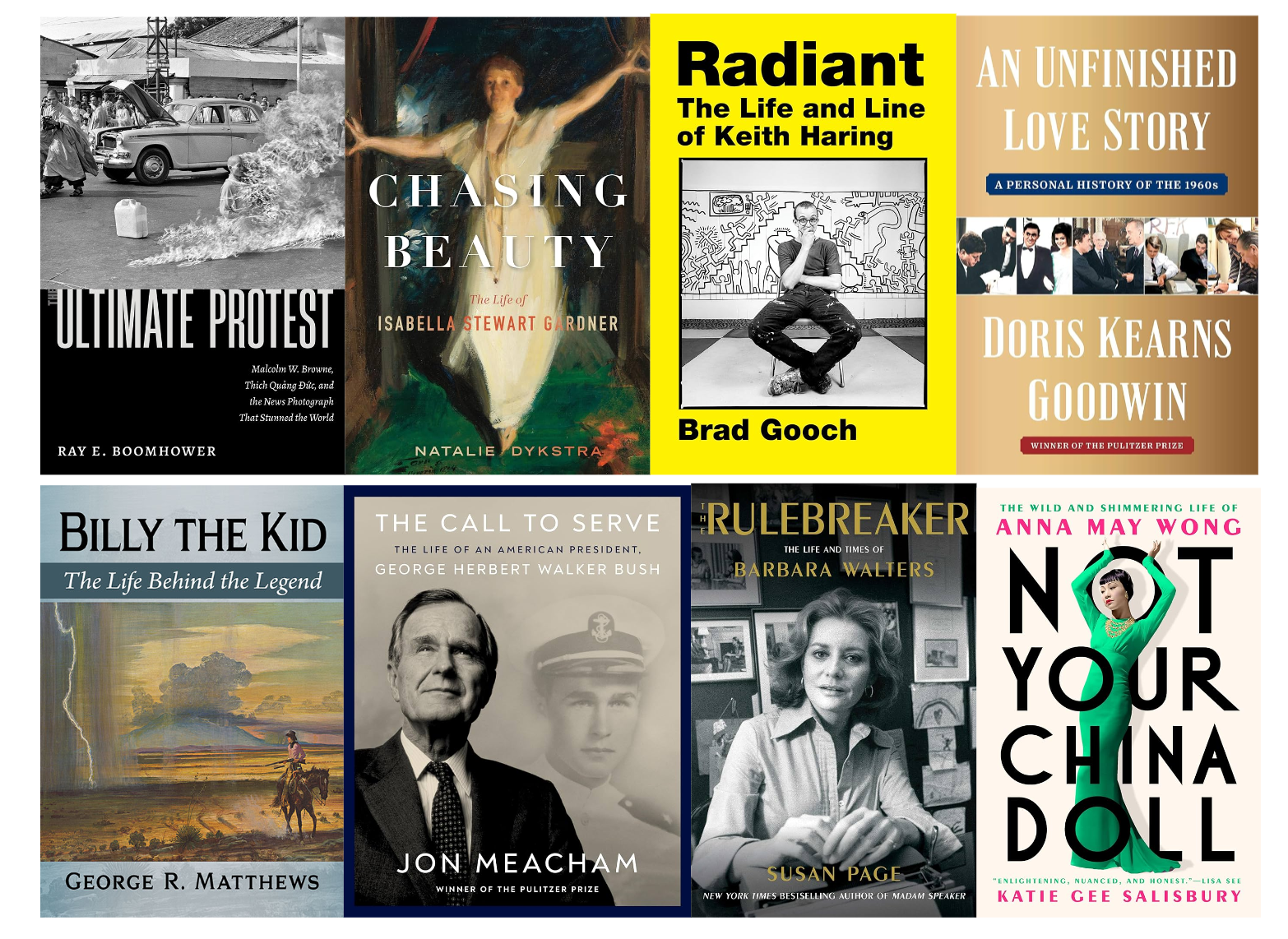

The Spring 2024 Preview: Biographies Coming Soon

Some of the biographies forthcoming from members of the BIO community.

Some of the biographies forthcoming from members of the BIO community.

It’s time to think spring! Here’s a roundup of biographies anticipated to be released between March and May, including information on their authors, publishers, and publication dates. The list is organized alphabetically by the author’s last name.

Once Upon a Time: The Captivating Life of Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy by Elizabeth Beller (Gallery Books, May 21). Considered one of the original “influencers,” Bessette-Kennedy was also a private and mysterious figure. Beller’s book will be the most formal biography written of her to date.

The Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Thich Quang Duc, and the News Photograph That Stunned the World by Ray E. Boomhower (High Road Books, March 15). Boomhower’s 19th book will explore the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam in 1963, Quang Duc’s self-immolation, and the only Western reporter who photographed the incident.

The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic by Daniel de Vise (Atlantic Monthly Press, March 19). After writing King of the Blues (the biography of B. B. King), de Vise is focusing now on the friendship between John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd and how their experiences led them to make the classic movie.

Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner by Natalie Dykstra (Mariner, March 26). Dykstra’s biography will tell the story of the founder of Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and will also describe how each item in the permanent collection forms a “memoir-in-objects” of its founder.

The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America by Sara B. Franklin (Atria Books, May 28). This biography of Jones promises a behind-the-scenes look at her 50-year publishing career, during which she nurtured writers such as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, and Julia Child.

Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring by Brad Gooch (Harper, March 5). Gooch’s biography stems from his receiving access to Haring’s extensive archives, from which he created an unprecedented work on the artist.

An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s by Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster, April 16). Goodwin’s latest work is said to blend biography, memoir, and history. It will explore how she and her late husband, Dick, embarked on a journey in the last years of his life to open and review all 300 boxes of their personal archives amassed from their time in government, politics, and publishing.

Joyce Carol Oates: Letters to a Biographer, edited by Greg Johnson (Akashic Books, March 5). This unusual collection of Oates’s correspondence with her biographer spans from 1975 to the present day. Johnson published a traditional biography of Oates, Invisible Writer, in 1998.

3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool by James Kaplan (Penguin Press, March 5). Jazz biographer Kaplan interweaves the story of three men into a group biography that portrays how jazz music reached its height in U.S. popular music in the 1960s.

The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President by Edward O’Keefe (Simon & Schuster, May 7). Theodore Roosevelt, a feminist? That’s what O’Keefe posits in this biography, which explores the five strong and determined women who shaped one of America’s most consequential presidents.

Billy the Kid: The Life Behind the Legend by George R. Matthews (McFarland, May 3). Matthews’s biography explores the origin story of Billy the Kid to provide a complete picture of the legendary figure.

The Call to Serve, The Life of an American President, George Herbert Walker Bush: A Visual Biography by Jon Meacham (Random House, May 28). Fresh off his Lincoln biography, And There Was Light, Meacham is releasing an innovative visual biography to commemorate the centennial of the 41st president’s birth.

The Rulebreaker: The Life and Times of Barbara Walters by Susan Page (Simon & Schuster, April 23). Page, the biographer of Nancy Pelosi—the most powerful woman who ever presided over the House of Representatives—has now written a definitive biography of the most successful female journalist in history.

Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong by Katie Lee Salisbury (Dutton, March 12). Salisbury explores Anna May Wong’s rise through Jazz Age Hollywood and her renunciation of it.

The Swans of Harlem: Five Black Ballerinas, Fifty Years of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History by Karen Valby (Pantheon, April 30). Valby explores the Dance Theatre of Harlem, an international dance company, through the experiences of prima ballerina Lydia Abarca and other members of the troupe.

Editor’s note: As a reminder, this is not an exhaustive list of all the biographies coming out this spring. Every month we track new releases in BIO’s The Insider. Be sure to send news of your books to our inbox.

|

|

|

|

CRAFT TALK

Dispatch From the Biography Lab: “Online Research Beyond Google” with James McGrath Morris

By Holly Van Leuven

As part of the second-annual Biography Lab on January 20, James McGrath Morris, one of BIO’s founders and a five-time biographer, led the “Online Research Beyond Google” forum, in which he shared many suggestions and recommendations for where to conduct research on the web. He also provided insight into how to extract valuable meaning from sources that may not seem inspiring on first glance.

Morris began the forum discussing the uses and limitations of ProQuest, a digital publishing company that offers one of the most extensive databases of periodicals and online resources available. ProQuest’s valuable holdings, however, come at a steep cost. “One of the things about ProQuest is that it’s extremely expensive,” Morris said, and ProQuest only sells subscriptions to institutions, not to individuals. Researchers with academic affiliations will usually be able to access their institution’s ProQuest offerings. Morris noted that independent scholars like him can frequently go to the libraries of public universities and be granted walk-in access to the institution’s ProQuest subscription, via their Wi-Fi or institutional computers.

“When you go to a library and you open up their ProQuest link, you may think you’re searching all of the 24 or so newspapers [that you see online] but you’re not, because . . . libraries don’t subscribe to every single one of those. They [only] buy a selection from ProQuest.” Morris said he advises would-be researchers to look at ProQuest’s own website first to ascertain what their offerings are, and then track down the library that can best serve them. (Some institutions may also offer remote access; check the library’s website or contact an archivist there.)

Morris also touched on the two other largest newspaper aggregators: newspapers.com, owned by Ancestry, and NewspaperArchive.com, now owned by Storied. These websites offer individuals affordable monthly subscriptions to their databases. While these and other archives may not contain the publications you are most interested in, Morris told participants why they are still worth a close look. He said, “The small newspapers they have in their collections often have remarkably useful information about things going on in large urban centers . . . because [these newspapers] used the Associated Press extensively.” And, as Morris pointed out, that was largely because the small newspapers were mostly driven to make revenue through ads and merely “wrapped news content around it to get readers.” Through this quirk, he explained, you could find “full-length, unabridged accounts of some society party in New York City or some event in Hollywood in the Galveston paper or the Sedalia Democrat.”

Morris also touched on the Chronicling America database, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities (as part of the National Digital Newspaper Program), which offers searchable, full-text periodicals online for free.

Beyond laying out key digital-research tools, Morris also provided suggestions, insights, and observations on the process of finding records. He said, for instance, “We are often anachronistic looking at the past. We think The New York Times was always the dominant paper in New York. We think The Washington Post was always the dominant paper in Washington. They weren’t. And the Washington Evening Star was so much bigger and better than The Washington Post for years, [that] if you’re doing research on anything that involves Washington, you want access to that paper, as well as to The Washington Post.”

Morris also said that he keeps a diary of what he has looked at while conducting research. An entry, he said, can be as simple as “Searched ProQuest newspapers on 1/18/24.” He said the reason to do this, particularly with online resources, is because many of the databases keep adding new material, so that in six months’ time, a researcher can return to the same database and get many more results to review.

People are also still important to the research process. As Morris reminded those in attendance, “Archivists around the country awake to open up their email in the morning and see a research inquiry, particularly if they have a lesser-used collection. It’s meaningful to them.” To find the archives and archivists who could be most helpful to a project, Morris recommended searching on ArchiveGrid.

Rampant digitization has provided researchers not just with access to more text, but to images as well. Morris encouraged attendees to think of photos more broadly than just illustrations for a book, few of which can ultimately be used. “Think of them as a way to help your settings,” he said. “When I did The Rose Man of Sing Sing [Fordham University Press, 2003], I built a set of photographs in my study, which had all the different parts of the prison. So, when my subject would leave one building to go to the other, I could imagine what he might see.”

Morris shared many other examples of how seemingly mundane primary sources could yield vibrant insights if considered in the right light. He said, “I used draft cards from World War II for my book on Tony Hillerman. And I discovered . . . he was a beanpole when he joined the Army, which is an interesting tidbit. But then it became a larger tidbit when I found out that the average . . . enlistees in World War II were too thin, and that’s part of the origins of the school lunch program after World War II.”

“When you start a project, you don’t necessarily know what’s important,” Morris said. “That’s why it’s best to capture what you learn as thoroughly and completely as possible.”

To hear more about the above research recommendations and many more, view the recording of the forum here.

|

|

|

|

MEMBER INTERVIEW

Six Questions with Matthew Lamb

What is your current project and at what stage is it?

Last November, I had published the first in a projected two-volume biography of Australian author and intellectual Frank Moorhouse (1938–2022). I’m currently working on the second volume. Moorhouse is best known for a trilogy of fiction books following a character named Edith Berry Campbell through the rise and fall of the League of Nations, finally resettling back in Australia to assist in establishing the nation’s capital in Canberra. But he has written many collections of short stories, starting in 1969. He developed his own form—the “discontinuous narrative”—that links all of his stories together. In total, his body of work is the most sustained imaginative feat in Australian literary history.

But at the same time, Australia has always had troubled literary culture, subordinated by a colonial deference to Britain, but also operating under an inadequate copyright system and a censorship regime that until the 1970s ranked among the worst in the world (not because it was particularly authoritarian, but because it was logistically easier for an island nation with few points of entry and a customs office with extensive search, seize, and destroy powers, to exercise its conservatism more effectively than most).

More so than in other Western countries, in Australia authors need to create the conditions within which they can write; they can’t just write. Many authors of Frank Moorhouse’s generation left because of these conditions (including Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes), but Moorhouse remained and was part of a generation that pushed back against these restrictions, overturned the censorship regime, and through a series of court cases established a copyright system that began to support rather than hinder a local writing culture. All while writing his own books. At the same time, he also led a complicated personal life, where his bisexuality and cross-dressing were often at odds with the conservative conventions of his own family and the nation at large.

Had Frank Moorhouse lived a smaller life, I would be writing a smaller book.

Who is your favorite biographer or what is your favorite biography?

I consider myself a reader, first and foremost, and only a writer by accident. The first great reading experience I had was facilitated by Deirdre Bair’s biography Samuel Beckett (1978). I read her book alongside the complete works of Beckett, in a chronological torsion: when I reached the chapter in Bair’s biography when, for example, in 1938, Murphy is published, I put down Bair’s book and started reading Beckett’s Murphy, before picking up Bair again, and so on. This reading practice has since become my norm. The high point was reading Joseph Frank’s multivolume biography of Dostoevsky in unison with Dostoevsky’s complete works.

I have also approached writing my own literary biography, as a reader. I’ve intentionally written Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths (2023) so that if the reader goes back and reads (or rereads) Moorhouse’s own books, they will be justly rewarded; their reading experience enhanced—but without being dogmatically directed.

At the same time, writing biography has forced me to consider more about the craft of the genre. So, I’ve turned to the work of Robert Caro. He really is the gold standard in biography. Reading his works on Moses and Johnson, as well as his reflections on biography itself, has allowed me to be unapologetic in my ambitions and critically honest in how and where I have fallen short.

What have been your most satisfying moments as a biographer?

Biography is very much a group activity, even if we sometimes don’t feel as if it is. It is often a collaboration with people we never even meet. I am not referring only to the subjects we write about and the individuals in their lives who become part of the stories we are writing—although that is also part of it. I am referring more to the people who have created the conditions and the materials that we use, in order to be about to tell these stories. The archivists, for example, who in the 1970s first started collecting material from Frank Moorhouse, so that when I began working on this project in 2015, it was with a sense that I was not starting something new, but continuing something that had begun long before I arrived on the scene. It is also the generosity of other researchers working in adjacent fields—several researchers, for example, who had written about subjects adjacent to Frank Moorhouse, graciously turned over recorded interviews and transcripts and materials otherwise not included in institutional archives. A library assistant in a high school library, for example, went above and beyond to unearth material from the 1950s (when Moorhouse went to that same school), including the earliest extant copy of a short story he had published in a student newsletter.

All these moments of discovery, and rediscovery—the most satisfying moments in the process—were because of the collaboration—knowingly, unknowingly, personally, or indirectly—with other people.

What have been your most frustrating moments?

The most frustrating moments have been when I lacked the resources to exhaust particular research lines of inquiry, especially those that required travel or doing long-term interviews (building rapport and returning time and again to the same subjects).

Compared to other Western nations, Australia is small, in terms of population, but with high illiteracy and an increasing de-literacy among the mainstream, which means it has a very small reading public—even smaller for books about the people who write the books that fewer people are reading. . . . As a result, there are also frustrations regarding the publishing process, where otherwise ambitious projects are scaled down to fit the low expectations of the local market. Frank Moorhouse was critically acclaimed, but he constantly struggled financially, constantly struggled against the conditions of publishing. But there are diminishing returns in writing a book about a man who never made any money writing his own books.

This is all partly the aftereffect of the long period of censorship and inadequate copyright support [in Australia], among the lack of other infrastructure and personal dispositions required to facilitate a literary culture. As Moorhouse researched, struggled against, and instituted corrections to this culture of neglect, this meant that I had to research that same culture, to cover much of the same terrain, in order to put his life and work into the broader context of Australian literary, legislative, and publishing history.

But the frustrations of that history were compounded when I had to personally enter into the same circumstances in order to get this book published. I would research and write about some obstacle that Frank faced in the 1960s, and again in the 1970s, and again in the 1980s—and then I would find myself confronting that same obstacle in my own experience.

The whole process was like being shown the instruments of torture before actually undergoing the torture myself.

One research/marketing/attitudinal tip to share?

For me, biography is itself a literary form. Writing biography is an act of imagination, first and foremost; just as reading it requires the engagement of the reader’s imagination, to activate rather than impose upon their judgement. It is precisely because of this that biography writing is so dependent on accuracy, precision, context, and a critical fidelity to the archive—as this is the only material we have available to us in order to select and arrange in a narrative form, in order to build up a moving, developing image of a particular life. Each biography is making an argument, in order to persuade the reader to consider the subject from a particular perspective. And as much as possible that perspective should be consistent with and proportionate to that underlying material, and the life as lived. But it is not absolute and can never be exhausted. It is for this reason that a biography can never be definitive, but is always discontinuous, always open to retelling and reinterpretation. This is what should keep us coming back, again and again, to reading and rereading Moorhouse’s books, and to keep open the question of his life and work. I’ve tried to incorporate that openness and discontinuity into this book.

What genre, besides biography, do you read for pleasure and who are some of your favorite writers?

As a literary biographer, it should not be a surprise that literary fiction is what I tend to read for pleasure. Currently, my favourite Australian writer is Jennifer Mills. Her work—such as her last two novels, Dyschronia (2018) and The Airways (2021)—humble and confound me. But my main area of concern is democracy; actual democracy, as both an idea and a practice and not the counterfeit we are daily offered. What is wonderful about this topic is that researching it requires engaging with a wide range of genres, both fiction and nonfiction, especially history, sociology, and political theory. I’m particularly interested in the African American intellectual tradition as it relates to the question of democracy. The work of Eddie Glaude Jr. is a touchstone for me. That said, I have just finished reading an astonishing new book, The Darkened Light of Faith: Race, Democracy, and Freedom in African American Political Thought (2023) by Melvin L. Rogers; it has kept me pacing my floor for days when I should otherwise be back at my desk working on the second volume of my Frank Moorhouse biography. . . .

Matthew Lamb is an Australian reader and author of the biography Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths (Knopf Australia, 2023). He writes on the relation between literary and democratic culture here.

|

|

|

|

AMANUENSIS

“The Art of the Mini Sales Pitch: How to Subtitle Your Book So People Will Read It”

by Tajja Isen

(originally published on Literary Hub)

About a year after my essay collection, Some of My Best Friends, was published, I got an email from my editor. Subject line: “Thinking caps, please: a new subtitle.” I’d known that this was coming. When we started kicking around ideas for the paperback, my team saw an opportunity to jazz things up. A new cover, a new subtitle. The hardback versions were beloved—by more than just me, I was reassured!—but it turns out that the original subtitle, Essays on Lip Service, had begun to strike people as a little too subtle.

“We want something that isn’t so vague,” my editor wrote, “and that very clearly tells you what you’re going to get in this collection: smart, incisive opinions; a perspective that may shift your own; some humor!” I love challenges like this; when you have to find the perfect way to sell a story to make it land with an audience. I also believe any exercise that asks you to compress your book into some sort of elevator pitch is never a wasted one. So, I was game, I was keen, I was dauntless. Even if a tiny part of me was miffed to discover I hadn’t gotten it right the first time.

Subtitles have become a mini sales pitch that obscures a book’s genre the way you might sneak a dog’s pills into a spoon of peanut butter. FULL ARTICLE

|

|

|

|

BIO PODCAST

Rachel Jamison Webster and Doug Melville

Recently on the BIO Podcast, Tamara Payne interviewed Rachel Jamison Webster, author of Benjamin Banneker and Us: Eleven Generations of an American Family (Henry Holt and Company, 2023); and Kevin McGruder interviewed Doug Melville, author of Invisible Generals: Rediscovering Family Legacy and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals (Atria/Black Privilege Press, 2023). New episodes are released every Friday here.

|

|

|

|

PITCH YOUR ARTICLE

Would you like to see your work featured in The Biographer’s Craft? Simply fill out this form to submit your pitch for consideration. Remember that features should be focused on the art and craft of biography, should not be promotional, and must be written by BIO members. Submit your pitch here.

|

|

|

|

KEEP YOUR INFO CURRENT

Making a move or just changed your email? We ask BIO members to keep their contact information up to date, so we and other members know where to find you. Update your information in the Member Area of the BIO website.

|

|

|

MEMBERSHIP UP FOR RENEWAL?

Please respond promptly to your membership renewal notice. As a nonprofit organization, BIO depends on members’ dues to fund our annual conference, the publication of this newsletter, and the other work we do to support biographers around the world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIO BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Steve Paul, President

Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President

Marc Leepson, Treasurer

Kathleen Stone, Secretary

Michael Gately, ex officio

Kai Bird

Heather Clark

Natalie Dykstra

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina

Carla Kaplan

Kitty Kelley

Susan Page

Tamara Payne

Ray A. Shepard

Barbara Lehman Smith

Kathleen Stone

Eric K. Washington

Sonja D. Williams

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Debby Applegate, Chair • Taylor Branch • A’Lelia Bundles • Robert Caro • Ron Chernow • Tim Duggan • John A. Farrell • Caroline Fraser • Irwin Gellman • Michael Holroyd • Peniel Joseph • Hermione Lee • David Levering Lewis • Andrew Lownie • Megan Marshall • John Matteson • Jon Meacham • Marion Meade • Candice Millard • James McGrath Morris • Andrew Morton • Arnold Rampersad • Hans Renders • Stacy Schiff • Gayfryd Steinberg • T. J. Stiles • Rachel Swarns • Will Swift • William Taubman • Claire Tomalin

|

|

|

THE BIOGRAPHER'S CRAFT

Editor

Jared Stearns

Associate Editor

Melanie R. Meadors

Consulting Editor

James McGrath Morris

Copy Editor

James Bradley

|

|

|

|