|

October 2021 | Volume 16 | Number 8

|

|

|

FROM THE EDITOR

From where I edit BIO’s publications in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania, the weather and the foliage seem to be marking time for the transition I have been engaged with this season. The mailing of this issue of The Biographer’s Craft marks the completion of my first “solo cycle” as editor (although Michael has been helpfully standing in the wings to answer questions!). Outside my office, the leaves are at the peak of their coloration and the temperatures are dropping, a good reminder of both the surprises and the constancy of change.

I have been involved with BIO for almost a decade, since I happened to be spending the summer of 2012 researching in Los Angeles and I stumbled upon that year’s conference on the USC campus. I arrived a hopeful, new biographer, and for many years I focused on getting that first book out into the world. With that accomplished, I wanted to give back to BIO for the practical help and the sense of warm community it provided me, and I am grateful for this opportunity.

This issue strikes a celebratory note, not least because of our extended look at the recipient of this year’s Editorial Excellence Award, Bob Bender. We also have a thoughtful and touching essay as part of our “Members’ Voices” initiative, and several other items that we believe will provide enjoyable reading for a cozy autumn evening. If you are not currently experiencing crisp air and golden leaves, consider that autumn may also be a state of mind.

Best Regards,

Holly Van Leuven

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIO Editorial Excellence Award Winner

TBC Talks with Bob Bender

As previously announced in the October Insider, Bob Bender will receive BIO’s 2021 Editorial Excellence Award, presented annually to an outstanding editor of biography, on Thursday, November 18, at 7 p.m. Eastern Time, during an online event featuring several of his authors: Marie Arana, David W. Blight, Scott Eyman, and Jeff Guinn.

Registration for the Zoom event is available at this link.

Bob Bender is Vice President and Executive Editor of Simon & Schuster, where he has worked since 1981. Reflecting on the many authors he has guided over his tenure, he told The Biographer’s Craft, “As the years went by I came to appreciate more and more the importance of quality writing. If a biographer can’t bring a subject alive, all the research in the world won’t save that biography. You must capture the reader’s attention and hold it if you hope to succeed.”

Bender acquires a wide range of nonfiction, including biography and autobiography, history, current events, popular science, popular culture (primarily film and music), and narrative nonfiction with a distinctive voice. Authors he has published include Muhammad Ali, Marie Arana, Miles Davis, Jonathan Eig, David Hackett Fischer, Linda Greenhouse, John Kerry, Naomi Klein, Pauline Maier, David McCullough, Gilda Radner, James Shapiro, and Jean Edward Smith.

In regard to biographies, Bender describes his taste as eclectic and noted that he has published the stories of figures from the ancient world (Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great); as well as more contemporary figures, like Dwight Eisenhower and Eleanor Roosevelt; important figures from other cultures, like Simon Bolivar and Samuel de Champlain; and, sports figures, cultural figures, and writers. “I’m interested in people whose lives tell us something new or different about their times or perhaps about our times,” Bender said.

Kai Bird, chair of BIO’s Award Committee, with Tim Duggan, Ruth Franklin, Peniel Joseph, Candice Millard, and Will Swift, praised Bender for his “cultivation and support for so many illustrious biographers over many decades.” Tim Duggan said, “In a business of constant change, Bob has been a stalwart at Simon & Schuster for decades, and his commitment to quality biography is without peer.”

Bender also shared some advice for working biographers:

“Choosing your subject is the most important decision you can make. Ask yourself why this subject is worth a biography. Has there been a good biography of this subject before? If so, has that biography been published recently? If the answer is yes, then ask why anyone would read your biography (or, perhaps, why anyone would publish it). If there has not been a good biography of your subject, is there a reason for that? Perhaps he or she is not a good subject to begin with. If there have been previous biographies of your subject, do you have something to contribute that previous biographers did not have, such as a distinctive point of view or a reinterpretation of the person’s achievements or a re-evaluation of how that person affected his or her times? Take your time choosing your subject because everything that follows hinges on that decision.”

Additional information about the event is available here.

|

|

|

|

MEMBERS' VOICES

Barbara Fisher On Carolyn Heilbrun, and When Our Models Make Models Out of Us

Editor’s note: Barbara Fisher, the 2019 recipient of BIO’s Hazel Rowley Prize, is continuing her work on a biography of Lionel Trilling, the proposal for which earned her the award. Here, Fisher has written a biographical essay on Carolyn Heilbrun, who is most famous for her classic feminist treatise, Writing a Woman’s Life. Heilbrun and Fisher crossed paths at Columbia University in 1969, when the former presided over a fellowship committee that the latter had applied to. Near the end of her life, Heilbrun authored the book, When Men Were the Only Models We Had: My Teachers Barzun, Fadiman, Trilling. Not only would Fisher take up the same subject that her professor had, but Fisher also had the unusual experience of being the unwitting model for a character in one of Heilbrun’s novels. The essay that follows is a thought-provoking meditation on choosing the models for our lives and the subjects for our life writing, as well as the mysteries that unfold as we explore who we really are in relation to others.

Barbara Fisher

Carolyn Heilbrun is best known for her books of feminist theory, such as Toward A Recognition Of Androgyny and Writing A Woman’s Life, but she also wrote a small book that few seem to know: When Men Were the Only Models We Had: My Teachers Barzun, Fadiman, Trilling. Published by the University of Pennsylvania in 2002, this compelling book describes a young woman’s earnest search for an appropriate academic model when there were none.

The three models Heilbrun found for her motivation, inspiration, and fantasy were, of necessity, men. There were no older women for a young woman to admire, emulate, or imitate. The few women who were literature professors at universities were sadly deficient as models. They were unmarried, unloved, and unbeautiful. Heilbrun did not want to be them, but she did not want to be excluded from the world of male accomplishment.

Thus, she was in the uncomfortable position of wanting to join a club that did not want her as a member. Even more uncomfortable was her desire to join the club while also wanting to dismantle it.

Before recognizing her wish to be a serious student of literature, she admired the unpretentious writing of Clifton Fadiman, whose modestly titled and popular book Reading I’ve Liked, she delighted in at the age of 15. Fadiman, whom she never met, considered himself a pitchman-professor, a popular commentator, a mere book reviewer. Heilbrun writes of him with affection and admiration for his curiosity, his precision, and his unpedantic prose.

She writes about her Columbia professor and subsequently her colleague Jacques Barzun with gratitude. Although terrifying at first, Barzun was kind and courteous to students. He happily shared with Heilbrun his interest in detective novels, as well as his appreciation of high culture. Most importantly and surprisingly, he offered her something like friendship as well as encouragement.

But it was Lionel Trilling—remote, diffident, and shy—who truly captured her spirit and her mind. Although she grew somewhat disenchanted with him, she treasures what he represented to her—an important kind of honor and courage and an “enduring gift for inspiring with its essential magic a piece of literature only seriously engaged with for the first time.”

But what drew her to him most powerfully was that he seemed to offer salvation. “Not religious salvation, of course,” she explained, “but a sense of how to live in a culture I both treasured and wished to overturn. What Trilling provided was an acrobatic balance between ‘bourgeois’ values and the need radically to affect them. It was in literature that he believed this balance, and profound instruction on how to live, could be found.”

When accused of having no position, of always being in-between, Trilling responded, “Between is the only honest place to be.” Between was where Heilbrun lived at the time.

I have tried to reconstruct how I came to know Heilbrun. I believe it happened like this. Heilbrun, as the token woman, sat on a committee that awarded fellowships in the spring of 1969, when I applied for financial aid to continue on for my second year in the graduate program in English literature at Columbia. Against her strong objections, the committee denied me the fellowship that she believed I deserved. She fought for me and lost, and then she sought me out to reassure and encourage me. It was an extremely kind and generous thing to do.

Though I hardly knew her when she brought me this comfort and consolation, I came to know her, value her, and confide in her.

Some of what I confided in her about my time at Bennington College, she borrowed for a character in one of the detective novels she was working on in secret at the time. Titled Poetic Justice and featuring her female detective, Kate Fansler, the fiction was published under the pseudonym Amanda Cross in 1970. The character who resembles me has been elegantly idealized. Stunning, beautiful, and expensively dressed, she is named, like me, Barbara. She is also fierce and fearless, and the only character in the novel with enough guts to deliver a scathing put-down to Professor Cudlipp, the villain of the piece. Lionel Trilling forms the basis for a major character in the same novel. Only slightly disguised as Professor Clemance, he turns out to be the unwitting murderer in the case. Many years later, when the portrait of Barbara in the fiction was brought to my attention, I was flattered by my cameo appearance and completely surprised to learn of Heilbrun’s second career.

I knew Carolyn in 1969–1970, at a time before she became an outspoken feminist, while she was still trying to be admitted to the unwelcoming Columbia fraternity. Denying her Jewishness and disguising her feminist beliefs, she moved uneasily and probably unhappily about Columbia. As one of the very few women professors on campus, she was a person of great interest to me, but she was not a figure I wished to emulate. Only later did she herself become a mentor, a model, and a heroine for me and for a multitude of smart, ambitious women.

Barbara Fisher is currently working on a biography of Lionel Trilling.

|

|

|

|

MEMBER INTERVIEW

Five Questions for Carol Sklenicka

What is your current project and at what stage is it?

I’m putting together a bibliography of Alice Adams for Oxford University Press because I hope more literary scholars will discover Adams’s brilliant, neglected short stories. Scribner published my Alice Adams: Portrait of a Writer just before the pandemic. I celebrated that nine-year project with a visit to my son in Denver and a reading at Tattered Cover Book Store. That audience included friends from several phases of my life—from a woman with whom I graduated high school in California to one I coached at a BIO conference in New York. Then my son and I watched a frightening Australian journalist’s report from inside Wuhan. I put on an N95 mask (I keep a supply in case of wildfire smoke) and flew home to northern California.

Thus began months of thinking about but not actually writing biographies. I’ve read biographies, and thought about how biographers’ lives intertwine with the lives of their subjects. I’ve talked about biographies on Zoom and podcasts, and evaluated manuscripts of biographies for friends and publishers. Through BIO’s coaching program, I’ve worked with other biographers to help them envision a book they hoped to write, or re-shape a book they’d already researched and first-drafted. This last activity offers me, I find, some of the rewards of writing and teaching: intellectual challenge and a small income. It’s thrilling to give first-time biographers perspectives or insights that shore up their courage and make their books come to life.

Meanwhile, I’ve tried to interest myself in biographical subjects that would not require travel. But I think these COVID months have changed me, turned me inward in ways that are probably more in keeping with what I can do in the eighth decade of this life. I’ve started reading and sorting stacks of letters written to me by my mother when she was the age I am now because, as one friend puts it, I’ve been “wanting to hear the voices of the long dead in my life.”

The upshot of all this is that I might write something about myself as a biographer. It’s barely an idea now, still finding its form.

Who is your favorite biographer or what is your favorite biography?

That’s another thing that’s changed through the years. The first one I remember reading was The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone. Later, Harry T. Moore’s The Priest of Love: The Life of D. H. Lawrence. After life tempered my romanticism, I favored John Wain’s Samuel Johnson: A Biography. Writing an article about Dr. Johnson in grad school led me to other lives of Johnson and taught me to analyze the genre. When I turned from criticism to biography, I dissected contemporary biographies to see how they were put together. Just now, I’m most impressed with biographies that have a rich historical context or controlling metaphor: Martha Bergland’s Birdman of Koshkonong; Caroline Fraser’s Prairie Fires; Timothy Egan’s Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher; Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments; Rollyson’s American Isis; and, Frances Wilson’s Burning Man: The Trials of D. H. Lawrence.

What have been your most satisfying moments as a biographer?

I love it when someone who knew my subject tells me I’ve taught them something or portrayed my subjects accurately. I’m equally proud when a friend of mine who doesn’t usually read biographies picks up my book out of duty and says, with evident surprise, that it “reads like a novel.” It’s also been extremely cool to see my name and the Alice Adams book cover in the Brief Reviews section of The New Yorker.

What have been your most frustrating moments?

My desire to write a biography of Raymond Carver was blocked by his estate’s objection to my project. Those objections frightened publishers and I wasted a lot of time doubting the validity of my ambition. If BIO had existed then, I would have known better.

What genre, besides biography, do you read for pleasure and who are some of your favorite writers?

Lately, I’ve been rereading novels—Hardy, Melville, Cather, Fitzgerald, Charlotte Brontë, Sarah Orne Jewett, Woolf, Kundera; discovering books that sat unread on my shelf for years—Old Jules by Mari Sandoz, Too Strong for Fantasy by Marcia Davenport, Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson; newer work including the recently translated Lucky Per by Henrik Pontoppidan, Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell, In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado. Less “pleasurable” but exciting because they shake up my notions of history: Michael Gorra’s The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste.

|

|

|

|

WRITERS AT WORK

Debby Applegate

How do biographers do what they do? Or more precisely, how do they organize the space where they conceive of projects, go through notes, write and rewrite their books? With Writers at Work, we offers glimpses into the working spaces of fellow biographers, with the writers describing what works for them and perhaps offering tips on what others should or shouldn’t do.

This month, Debby Applegate shows us where she works.

Please share with us pictures of where you work, so we can include them in future issues.

|

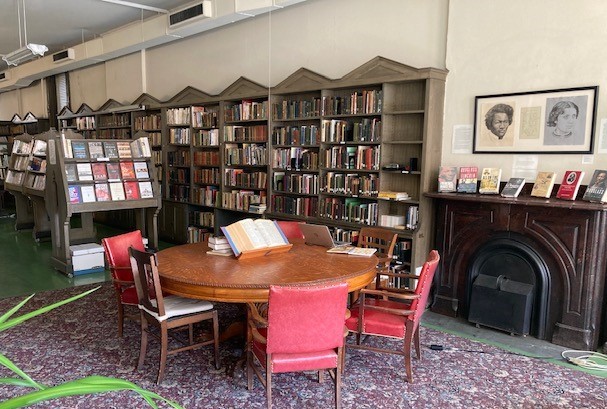

Of her august workplace in New Haven, Applegate says: “Until COVID-19 arrived, I worked in the hushed confines of the Day Missions Library of the Yale Divinity School, where I was once shushed by a young divinity student for sighing too much. (It was an especially frustrating day.) When the pandemic forced Yale to shut their libraries to outside scholars, I found a new refuge in the New Haven Institute Library. Founded in 1826 by the Apprentices’ Literary Association in pursuit of ‘mutual assistance in the attainment of useful knowledge,’ it is one of only a handful of membership libraries in the United States—and with annual membership a mere $25, it is an antiquarian treasure at a bargain price.”

|

|

|

|

AMANUENSIS

“How Do I Tell the Story of Robert E. Lee?”

by Allen C. Guelzo

(from The New York Times)

This month in Virginia, the most famous statue of Robert E. Lee—a 21-foot-tall bronze equestrian sculpture—was swung down from its granite base on Richmond’s Monument Avenue and cut in two at the waist so that it could fit under highway overpasses on its final journey to an undisclosed state facility. Hundreds gathered to cheer the event as a victory for racial justice.

I wondered whether the same toppling awaited my biography. I called my editor: Should we just put this manuscript in the freezer? My editor found my courage for me. No, he replied, we want to go ahead with this. If anything, he assured me, a thorough, unflinching and humane biography of Lee is more important now, as the monuments to him have been removed from view. That put me back on the rails.

There are some biographies that are almost impossible to write, but write them we must. Biography demands a close encounter with a subject, an entrance into motive, perception, and explanation. The intimacy of that encounter carries with it the danger of dulling the edge of the historian’s moral judgment—and that kind of judgment is what makes historical inquiry worthwhile, something more than a mere jumble of events and dates.

Difficult biographies present a challenge not unlike the one experienced by lawyers who have to make convincing cases for repulsive clients. They make for difficult work, but you cannot leave them unwritten, any more than Plutarch or Suetonius did. Without the warning signs that difficult biography sets out, we could easily lapse into the comfortable persuasion that evil, wrong and injustice have no substance, and we would lose the sharpness of vision that tells us the difference between the path to human flourishing and the off-ramp to disaster. FULL STORY

Amanuensis: A person whose employment is to write what another dictates, or to copy what another has written. Source: Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913).

|

|

|

|

KEEP YOUR INFO CURRENT

Making a move or just changed your email? We ask BIO members to keep their contact information up to date, so we and other members know where to find you. Update your information in the Member Area of the BIO website.

|

|

|

MEMBERSHIP UP FOR RENEWAL?

Please respond promptly to your membership renewal notice. As a nonprofit organization, BIO depends on members’ dues to fund our annual conference, the publication of this newsletter, and the other work we do to support biographers around the world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

SUBSCRIBE

To The Leon Levy Center for Biography's Mailing List

Would you like to learn about free virtual events featuring excellent biographers? The Leon Levy Center for Biography has a robust schedule of events for Autumn 2021. Subscribe here to receive information on forthcoming offerings from LLCB and to learn how to access previous ones.

|

|

|

|

BIO BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Linda Leavell, President

Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President

Marc Leepson, Treasurer

Steve Paul, Secretary

Kai Bird

Heather Clark

Natalie Dykstra

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina

Anne Heller

Carla Kaplan

Kitty Kelley

Anne Boyd Rioux

Holly Van Leuven

Eric K. Washington

Sonja D. Williams

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Debby Applegate, Chair • Taylor Branch • Robert Caro • Ron Chernow • Tim Duggan • John A. Farrell • Irwin Gellman • Michael Holroyd • Peniel Joseph • Hermione Lee • David Levering Lewis • Andrew Lownie • Megan Marshall • John Matteson • Jon Meacham • Marion Meade • Candice Millard • James McGrath Morris • Andrew Morton • Arnold Rampersad • Hans Renders • Stacy Schiff • Gayfryd Steinberg • T. J. Stiles • Will Swift • William Taubman • Terry Teachout • Claire Tomalin

|

|

|

|

|

THE BIOGRAPHER'S CRAFT

Editor

Jared Stearns

Associate Editor

Melanie R. Meadors

Consulting Editor

James McGrath Morris

Copy Editor

Margaret Moore Booker

|

|

|

|