|

November 2023 | Volume 18 | Number 9

|

FROM THE EDITOR

It’s the unofficial start of the holiday season, but the happenings in biography show no sign of slowing down. In this month’s Biographer’s Craft, you’ll find advice and hopefully inspiration in the words of Michael Korda, who received BIO’s Editorial Excellence Award at a ceremony in New York City earlier this month; Walter Isaacson, who recently gave the annual biography lecture for the Leon Levy Center; and Barbara Weisberg, who sat down with us for our monthly member interview.

There’s still time to send along member news for the December Insider. Send us a postcard, drop us a line here!

Sincerely,

Holly

|

|

|

|

CRAFT NOTES

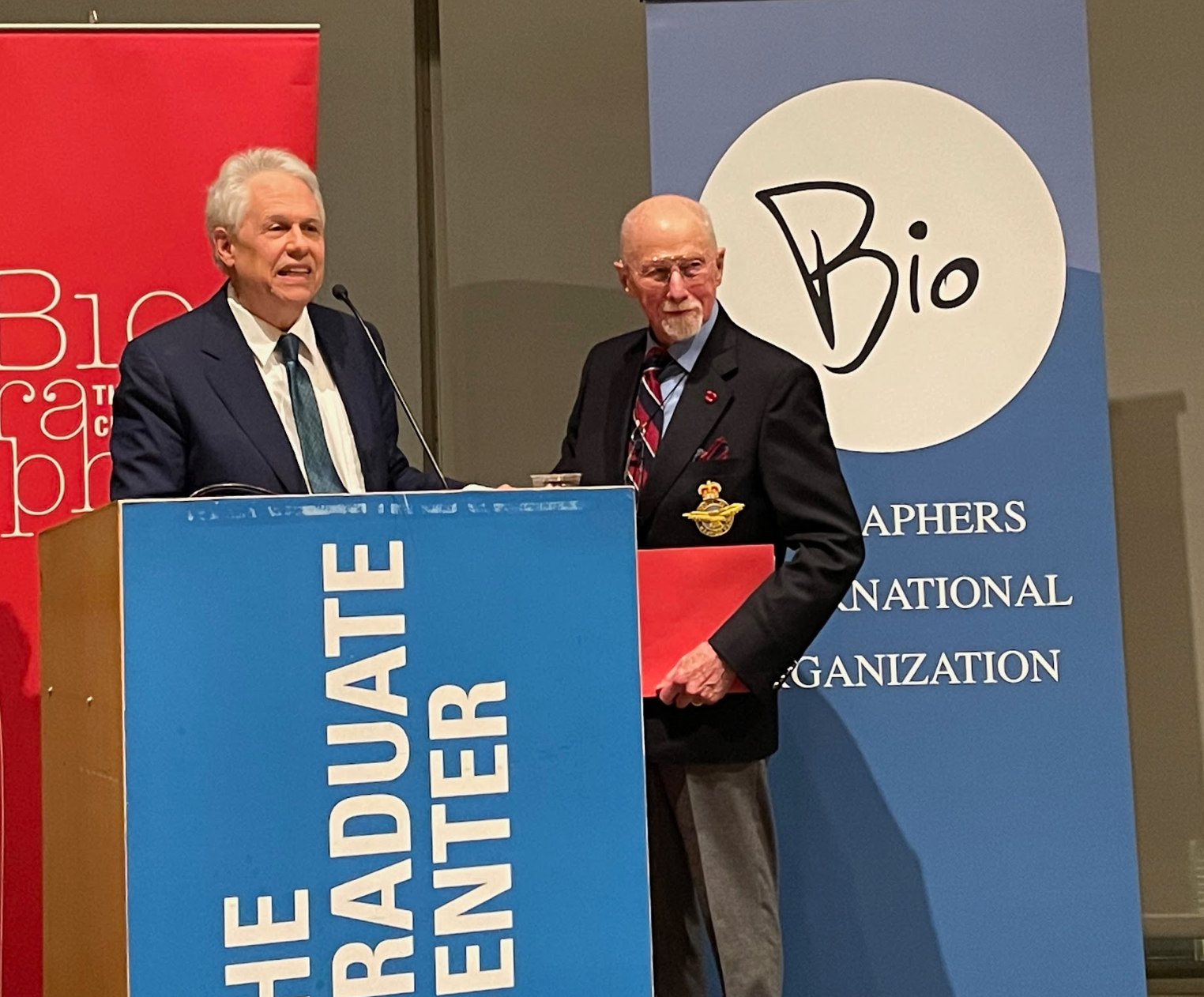

Michael Korda’s Editorial Excellence Award Acceptance Speech

Will Swift (left) and Michael Korda (right). Photo courtesy of Eric K. Washington.

Will Swift (left) and Michael Korda (right). Photo courtesy of Eric K. Washington.

by Michael Korda

Editor’s Note: Michael Korda was honored as the 10th recipient of BIO’s Editorial Excellence Award for his service to biography at the Skylight Room of the CUNY Graduate Center in New York on November 1.

Korda was an editor, and later editor-in-chief, of Simon & Schuster for nearly five decades. Among the more than 500 books he worked on, he edited all three of David McCullough’s prize-winning biographies—of Harry Truman, John Adams, and the young Theodore Roosevelt—as well as autobiographies by Ronald Reagan, Henry Kissinger, Kirk Douglas, and Charles de Gaulle.

He has written biographies of Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, and T. E. Lawrence, as well as several works of history, including one about the Battle of Britain and one about Dunkirk. His book about the lives of the major soldier-poets of World War I, Muse of Fire, will be published in April 2024, by W. W. Norton & Company.

At the event, Heather Clark, the chair of BIO’s Awards Committee, introduced four in-person speakers who paid tribute to Korda: Moira Hodgson, author of It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: My Adventures in Life and Food; Robert Weil, the executive director and vice president of Liveright, an imprint of W. W. Norton & Company, who has edited three of Korda’s books; Victoria Wilson, vice president and executive editor at Alfred A. Knopf; and Simon Winchester, a British writer, journalist, and broadcaster.

Korda made the following acceptance speech.

From the time I started reading, I read biography. I don’t think I ever read a novel until I got to boarding school in Switzerland in 1947, and was required to read (in French) Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes, a slow read, by the way, if ever there was one, which further convinced me that reading biographies was more fun.

From an early age, I had the unfettered run of my father’s books, which filled and overfilled shelves and tables all over our house. He didn’t mind what I read, provided I was reading, rather than distracting him from collecting art and designing the sets for my Uncle Alex’s movies.

The sight of me with a book in my hands—the heavier, the better—reassured him that I was not wasting my time and also was not going to bother him with questions or what he would call “chitchat.” It also taught me a lifetime lesson, that there is a big difference between “doing nothing” and sitting in a chair reading a book. Reading a book is a respected activity. No child holding a book in their hands is considered to be wasting their time by adults, even if the child’s eyes are closed.

My father was a not a reader of fiction. He preferred biographies and history, in English, French, German, and of course his native Hungarian, and his bedside table was piled high with whatever he was reading, since he tended to switch back and forth between books, as I do, rather than to read one straight through before starting another.

The first “grown-up” book I remember reading was Carola Oman’s humongous Nelson, and I dived into it like someone entering a swimming pool, unable to stop reading. I should explain that my father had designed the sets for my Uncle Alex’s That Hamilton Woman, that most English of historical epics, starring Larry Olivier as Nelson and Vivien Leigh as Lady Hamilton, although practically everybody involved on the production side was Hungarian, hence the presence of Carola Oman’s classic biography of Admiral Nelson on my father’s shelves. Due to a misunderstanding between the two brothers—the film was being made in a hurry—the first set my father built was for the Duke of Wellington’s library in Brussels, just before the Battle of Waterloo, and when Alex saw it, he said to my father, “Vat the hell is this, Vincekem, I meant the bloody admiral, not the bloody general!” My father and his “boys” had to turn Wellington’s library into Lady Hamilton’s bedroom overnight, with the Bay of Naples outside the window, and Nelson’s ship, H. M. S. Agamemnon floating in it, firing a salute. The word “impossible” does not exist in the movie business.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the next biography I read, probably because it was next to Carola Oman’s Nelson on the shelf, was Sir Arthur Bryant’s The Great Duke, his life of the Duke of Wellington, which got me started on reading biographies of 18th-century figures, and for a lifelong fascination with military history. I developed a certain unhealthy fixation on the Prince Regent, later King George IV, whose life has inspired countless biographies, and by the time I arrived at Le Rosey, my boarding school in Switzerland, at the age of 13, I knew more about Georgian life, literature, and politics than any other pupil there—more certainly than was good for me. I even took to carrying an antique sterling silver snuff box in my pocket.

To this day, I still feel almost as much at home in the 18th century as my own, and when I read a book like Stacy Schiff’s wonderful biography of Samuel Adams, nothing in it seems to me quaint or unfamiliar or long ago. L. P. Hartley’s famous line, “The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there,” is certainly true, up to a point. But to a biographer, the interesting thing about human lives, on the contrary, is the degree to which they do things the same—they are moved by the same needs, the same weaknesses, the same concerns, from generation to generation, from one century to the next. The political reality in which they live may change, as do the clothes they wear, but in their innermost life people are more alike than not, from the ancient Romans to ourselves, and part of a biographer’s task is to pierce through the obvious things that separate us from people of other times and illuminate, that is bring to life, the person within. Even the great monsters of history have their human side, after all, from Hitler’s love of dogs to Ivan the Terrible’s remorse for the killing of his son, or Attila the Hun’s apparent fondness for his sons. It is one of Stacy Schiff’s great achievements, by the way, that she takes Cleopatra out of the mists of myth and turns her into someone we feel we know, and whose motives we understand.

One of the books I reread most often is Garrett Mattingly’s The Defeat of the Spanish Armada because of the masterly way in which he combines “the big picture” of history with brilliant sections of biography—not to speak of a profound knowledge of sailing and seamanship—into a single narrative. Another is Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August, which again combines wonderful biographies of each of the major characters within a brilliant narrative of the first month of World War I. I have never forgotten the sharp cutting edge of her portrayal of Field Marshal Sir John French, the volatile commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force, so clearly the wrong man in the wrong place at a critical moment of history, yet somehow, in her hands, also an appealing and perhaps all too human figure, who might have stepped out of a Nancy Mitford novel.

Writing history tends to make us take the long view, to describe sweeping vistas and big events, while writing biography tends to make us concentrate, to seek out the small events, the unexpected words or actions that reveal the person behind the mask, or the legend.

Biography is not about sweeping theories of history, it is about facts, about what people felt, saw, did, wrote. There is a wonderful story about a state visit of Queen Victoria’s to Paris in the mid-19th century, that as she and the Empress Eugénie sat down in the imperial box at the Paris Opera, Eugénie glanced briefly behind her as she sat down to make sure her chair was slipped into place, whereas the queen sat down without looking behind her—from childhood she had always been confident that her chair would be put in place by someone as she sat down. It was the difference between one who was born to royalty and one who came to it unexpectedly, later in life. These are the little human touches that make biography different from history, and very often give us a better view of the past than lengthy descriptions of battles or political debates. To the biographer, every little thing is useful if it illuminates a character or a personality—it is inevitably portraiture, rather than a big vista, but arguably it is the best way of presenting or explaining history.

Disraeli wrote that he read no history—“nothing but biography, for that is life without theory”—and who would know better? For what is history but the sum total of people’s lives? By examining one person’s life in the context of their time, we are likely to learn more about that time than by sweeping descriptions of events.

When the Abbé Sieyès was asked what he did during the French Revolution, he replied simply, “Je l’ai survécu,” I survived it, which tells us more about what the revolution was like than a dozen heavy histories of [The Reign of] Terror.

By putting “the human element” back into history, the biographer gives us a true picture of what the past was like, for it is not in descriptions of the great historical set pieces that we form a meaningful picture of the past, but in the lives of people great and small, what they thought, what they said, what they wrote to each other, how they felt about the events going on around them, that we understand what was actually happening.

I am often asked whether I like the people I write about, but I think the more important thing is to keep an open mind about them. Writing a biography is an adventure, a journey of discovery. It is only as you begin to read about your subject, and above all to read his or her letters, that you begin to really know him or her. I rather vaguely admired Ike when I set out to write a biography of him, but it was only as I began to understand his family, to think about how unusual it was for a boy from a Mennonite family, all devoted pacifists, to go to West Point, become a soldier, then on to being a supremely successful general, that I began to like him, and to realize how complicated the real man was behind that famous big grin. The same was true for Ulysses S. Grant, who at first seemed like an unpromising subject but whose character snapped into focus when I read about his first encounter with the enemy in 1861, when he led his fledging regiment toward the camp of a Confederate colonel, who had been harassing local farmers in Missouri, over the brow of a hill to attack. As he did so he thought, “I would have given anything to be back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt,” a thing not many four-star generals would later admit to, but when he discovered that the Confederates had fled at his approach, he realized that the Confederate colonel “was as much afraid of me as I had been of him,” and reflected “that was a view of the question that I had never taken before, but it was one I never forgot afterwards.” Like Ike unholstering his pistol, getting out of his car, and moving forward on foot when his driver mistakenly drove him into the front line in Tunisia in 1942, in the middle of a firefight, it was a moment that firmly defined Grant’s no-nonsense calm, courage, and good sense.

It was that same steadiness that marked Grant’s character when Sherman rode up, dismounted, walked up to him in the rain on the night of the first day of the Battle of Shiloh, to find his commander-in-chief sitting huddled up under a tree smoking a cigar after what was then the bloodiest day in American history. Grant hated the smell and sight of blood—he would not eat meat, even turkey, unless it was well done, like shoe leather—and all the barns and houses around the battlefield were being used by surgeons, chopping off limbs, the last thing he wanted to see, so he was sitting outside in the rain, smoking a cigar. Sherman, who at that point did not know him well, said, “Well, General Grant, we sure took a licking today,” to which Grant replied calmly, “Yep, beat ‘em tomorrow though.” Which he did.

It is these little human touches that, frankly, make biography such a treat to write. The constant small discoveries that make one say, “Oh, he or she couldn’t have done or said or thought that,” are the equivalent of opening a surprise Christmas present from under the tree and unwrapping it to discover it was exactly what one had been hoping for.

The only thing more enjoyable than writing a biography is reading a good one, so it is an honor, as well as a pleasure, to be here tonight, among people who have shared the pleasures, the surprises, and the occasional sadnesses of delving deeply into someone else’s life. Most biographers, I think, end up loving the person they are writing about, despite his or her flaws and mistakes, otherwise it would be hard indeed to spend several years in the company of a total stranger one dislikes—I am in awe of Bob Caro, who spent 49 years in the overbearing company of Lyndon Johnson!—and certainly I have come to think of my subjects at least as friends, whose company I enjoy, whose mistakes I try to avoid, and whose example I try to follow.

I can’t think of any other kind of reading that over the years has given me more pleasure.

The recording of the full event is now available for viewing here.

|

|

|

“Not All Steel is Stainless”: Walter Isaacson on Writing About Difficult Figures

by Holly Van Leuven

Walter Isaacson, noted biographer of scientists and innovators, gave the Annual Leon Levy Biography Lecture, on the craft of writing and researching biography, on September 28. In his lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center, Isaacson, who is also the former CEO of CNN and former editor of Time magazine, touched on many of the 10 biographies he’s written, while taking the audience through a one-hour lecture about the art and science of biography.

Isaacson’s first biography, The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made, was co-written with Evan Thomas and published in 1986. The group biography centered around the policymakers Dean Acheson, Averell Harriman, George Kennan, John McCloy Jr., Charles Bohlen, Robert Lovett, and their work following World War II. This began Isaacson’s exclusive publishing relationship with Simon & Schuster, which published his next book, Kissinger: A Biography, in 1995. While working on his Henry Kissinger project, Isaacson said he “learned the value of combining journalistic interviews with research in the archives.” The alloy of these two sources, however, led to new conundrums. Finding memos and letters sent to and from Kissinger in places like the Library of Congress and the archives of the Council on Foreign Relations felt like a boon. But, Isaacson said, “When I interviewed Mort Halperin and Winston Lord and others who had actually written those memos of conversations, they told me, ‘Oh, those aren’t true. Those were made up.’” The reasons for the fabrications were that Kissinger wanted to impress Nixon and/or confound future historians.

On the flip side of the same coin, Isaacson discovered what he called the “And then I Told the President” problem, while interviewing John McCloy, the former U. S. assistant secretary of war under FDR, about dropping the atomic bomb. Isaacson said, “[McCloy] told the story of being at a meeting and at one point he said, ‘And I told the president to be wary about dropping the bomb.’ I went through the oral histories that McCloy had done starting in the 1950s, and I realized that he had gradually embellished that story.” Isaacson said that in the earliest documents, McCloy claimed he was not even sitting at the table for the meeting but was merely on the outskirts of the room, and that he later talked to his own boss, Henry L. Stimson, then the secretary of war, not the president. Showing how closely art and science are intertwined in even his process of researching and writing biography, Isaacson said, “When you’re interviewing powerful people, it’s like the half-life of uranium: [for] each decade, you have to discount 20 percent of some of their memories.”

Isaacson discovered that some of his subjects also brought the laws of science to bear on other facets of their life and work. Through researching Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (Simon & Schuster, 2003), he said, “One of the things I learned from researching Franklin is how important science was to him. His appreciation for Newtonian mechanics helped inform the checks and balances of power that he and Jefferson, also a good scientist, [created].”

This book was followed by a study of another great scientist, Einstein: His Life and Universe, published in 2008. In this book, Isaacson had crossed the Rubicon: rather than writing about how policymakers shaped the world, he focused on how scientists did.

After publishing these five biographies, Isaacson’s readers began to notice themes in his work. Close to home, his daughter made him aware of some jarring commonalities between his biographies and his own life. “My daughter said I wrote about Franklin because I was writing about myself, a somewhat ambitious, upwardly striving journalist who aspired to be involved in public policy and liked technology.” Isaacson said he then inquired of his daughter why he had written about Albert Einstein. She replied that he chose Einstein because he represented Isaacson’s own father, who was a successful engineer. Then he asked her to explain why he had written about Kissinger: “She said, ‘Oh, dad, you were writing about your dark side.’”

Isaacson was more surprised when Steve Jobs found a theme in his work: that innovation comes from those who stand at the intersection of the arts and the sciences, which was exactly the space from which Jobs ran Apple. It was for this reason that Jobs asked Isaacson to be his biographer, about two years before he died. Isaacson agreed, and Steve Jobs was published in October 2011, just weeks after the entrepreneur’s death. While interviewing his subject for that book, Isaacson said Jobs made a suggestion for his next biographical subject: Leonardo da Vinci. Isaacson accepted the challenge.

While researching that subject, which became Leonardo da Vinci (2017), Isaacson said he discovered a letter in the archives that illuminated how even the original Renaissance man struggled to balance his artistic side with his scientific side. He said, “[Leonardo da Vinci] decides to go off to Milan and he writes the Duke of Milan an 11-paragraph letter. He says, ‘I can build bridges. I can make great buildings.’ Only in the 11th paragraph does he say, ‘I can also paint.’”

Isaacson discussed his biography of Elon Musk, published in September, at great length. Musk, he said, was someone he also found to be an amalgamation—not of art and science, rather of light and dark. Isaacson only agreed to write the biography on the condition that he be allowed to shadow Musk for two years and that he would not have to show his subject the manuscript in advance of publication. The entrepreneur agreed, and Isaacson set out to write a straightforward biography about a scientifically minded genius who was better at getting rockets into orbit than NASA and who “nearly single-handedly” pushed the electric car revolution forward when players like Ford and GM had given up.

Not long into the shadowing, Musk told Isaacson a secret: he was planning to buy Twitter, long before it was public knowledge. Also, during the shadowing, the war in Ukraine broke out. As the owner of Starlink, Musk found himself with a great deal of power when it became clear only his satellite internet could operate in Ukraine after Russia destroyed the country’s infrastructure. By then, Isaacson knew he would be writing a completely different book, and a more complex one, than the one he had first envisioned. The result was Isaacson writing, publishing, and promoting a book about a person with genuinely admirable and seemingly superhuman qualities in a climate where the public, outraged by Musk’s very public antics, had little interest in seeing that side of him.

One of the conundrums a biographer must contend with today, Isaacson said, is receiving criticism for laying out the origins of a subject’s character flaws and tracing those traits narratively through a biography. He said, “If you try to explain somebody’s behavior, and if you try to understand his behavior, people think you’re excusing that behavior, which is difficult because I’m trying to tell it as a story. I’m trying to let readers make judgments, but I’m also trying to figure out the roots of a particular type of behavior.” Continuing, Isaacson said, “Admiring a person’s good traits while decrying their bad ones is simple compared to the more complex challenge of understanding sometimes how those strands weave together, how they might be tightly interwoven. They might be inextricable. You can’t say, let’s take away Musk’s Twitter feed and take away his dark tweets and take away his bad political things, but also keep the impulsive person who shoots off three rockets, all of which explode, and, as he’s going bankrupt, gets a fourth attempt and turns [it] into SpaceX.”

Musk, according to his biographer, has an innate understanding of the material sciences “and how the compounds of an alloy draw their strength from their combination, a combination of elements that . . . produces properties that don’t exist when you pull out any one of those elements.”

Isaacson summed up his philosophy of biography as only a biographer of sciences could: “There are very few unalloyed players on history, and that’s particularly true of innovators. Not all steel is stainless.”

|

|

|

|

MEMBER INTERVIEW

Six Questions with Barbara Weisberg

Barbara Weisberg is the author of Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism (HarperOne, 2004) and the forthcoming Strong Passions: A Scandalous Divorce in Old New York (W. W. Norton & Company, 2024). She answered November’s “Six Questions.”

Who is your favorite biographer or what is your favorite biography?

I read Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain many decades ago, and it made me realize—believe it or not, for the first time—that authors weren’t just names with accompanying paragraphs in encyclopedias but individuals with complex psyches and complicated lives and stories of their own, apart from the ones they told in their books. That recognition forever enriched my reading experience, valuable whether or not in any given case I was looking for how a writer’s life influenced the work. I’ve never forgotten the excitement I felt reading Justin Kaplan’s biography of Twain. I actually have just reordered it, and look forward to rereading it.

What person would you most like to write about?

I had an eccentric great-uncle, moderately influential in his own time—enough so to merit a front-page Times obituary in the 1950s—about whom someone wrote a controversial biography in the 1960s. I knew my great-uncle only slightly (and remember his pet parrot more vividly than him) but have always been curious about him. Why did he choose to live the unconventional life that he did? What were the sources of his notable obsessions? Was his influence in fact greater than has been acknowledged? And why have I avoided writing about him until now? The answer to the last question, of course, is family memories. In writing about him, what else will I uncover in the attic of my brain?

What have been your most satisfying moments as a biographer?

In doing research for Strong Passions, I turned to the Archives of the New York County Clerk to look for trial documents. My guide there was the amazing archivist Joseph Van Nostrand. Joe immediately brought me the bound Volume 16 of the Superior Court’s Divorce Records. It had great material, and he kept it where I could always find it, even if I didn’t return to the archives for weeks. Then one day he emailed me: he hadn’t given up his own search and had found more documents. Uncatalogued, hidden on a shelf in a back storage room, rolled up and tied with ribbon, stuffed in a torn paper bag were pages of yellowed depositions from 1865. That bag contained depositions that had never been read in court or covered in the press. Among other things, I learned that the adulterous wife’s lover in my book had confessed to their affair. Oh, those eureka moments!

Joe passed away earlier this year. I feel so lucky to have worked with this indomitable archivist.

What have been your most frustrating moments?

Of course, one could always have the opposite experience: disappointment. I couldn’t believe my luck when I found two volumes of personal letters written by an important member of the family I was researching. At the time, the volumes appeared on a fairly obscure private website, although they later were posted on a public site. Unfortunately, I soon realized that there was a 10-year gap covering the exact period I wanted to write about. Those undoubtedly revealing letters had all been lost, omitted, or destroyed.

What genre, besides biography, do you read for pleasure and who are some of your favorite writers?

What I usually read and how I read—day or night, porch or study, tomes or glossies—changes a lot from year to year, depending on where I am in my life. Right now, I’ve been finding welcome relaxation in mysteries, including those by Donna Leon, Louise Penny, and Adrian McKinty, and comfort in rereading favorite 19th-century novels, however unhappy, including The Portrait of a Lady and Wuthering Heights.

One research/marketing/attitudinal tip to share?

I seem outgoing but often feel somewhat shy, so one of my friends suggested that I think of marketing my book as playing a role in a play. She suggested that whenever I have a professional activity that involves self-promotion, I become a character in this imaginary play, one who is outgoing and confident, even a little bold. Together, we gave this character a name, and I become her in my mind when I need to make a phone call, write a blurb, or do a presentation. How weird is that! This might not be a tip that works for everyone, but it works for me!

Learn more about Barbara Weisberg here.

|

|

|

|

AMANUENSIS

The Matchbook in the Archives: Where and When Does Inspiration Strike?

by Bonnie Clause

In the Archives of American Art, I once found an intact book of matches, dutifully filed by some assiduous intern, perhaps, overly cautious in observing the “do not dispose” dictum to the point of forgetting what fire might do to that folder’s disposition and, indeed, to that of the entire archives. Some days, this is all one turns up, an amusing anomaly within a disappointing collection that documents, in boring multiplicity, already well-known facts. And then there are the surprises: open a folder, turn a page, and suddenly there’s something that brings the subject to life, an unexpected biographical detail revealed or, best of all, a letter penned by hand, a creation as personal as a painting or a poem. Or a draft, with things crossed out, recording the ease or difficulty with which it was executed. Maybe a mystery: who is M (or L or Z) to whom this letter is addressed? Was it ever sent? Diary entries, especially elliptical ones, raise tantalizing questions for would-be detectives. Again, there are those references to people by initial only; might they be lover, friend . . . or a favorite dog? Are the shorthand notations disguising a clandestine affair, or are they merely scribbled in haste rather than in code, a past generation’s version of texting? Sometimes there are no further answers, only clues that lead to dead ends. Other times, these bits and scraps and scribbles are like pieces of a puzzle, over time finding their rightful place in the bigger picture that I’m wanting to reveal . . .

|

|

|

|

BIO PODCAST

Recently on the BIO Podcast, Jennifer Skoog interviewed Mary Ann Caws, author of Mina Loy: Apology of Genius (Reaktion Books, July 2022); and Kitty Kelley interviewed Edward O’Shea, author of Seamus Heaney’s American Odyssey (Routledge Press, December 2022). New episodes are released every Friday here.

|

|

|

|

KEEP YOUR INFO CURRENT

Making a move or just changed your email? We ask BIO members to keep their contact information up to date, so we and other members know where to find you. Update your information in the Member Area of the BIO website.

|

|

|

MEMBERSHIP UP FOR RENEWAL?

Please respond promptly to your membership renewal notice. As a nonprofit organization, BIO depends on members’ dues to fund our annual conference, the publication of this newsletter, and the other work we do to support biographers around the world.

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIO BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Steve Paul, President

Sarah S. Kilborne, Vice President

Marc Leepson, Treasurer

Kathleen Stone, Secretary

Michael Gately, ex officio

Kai Bird

Heather Clark

Natalie Dykstra

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina

Carla Kaplan

Kitty Kelley

Susan Page

Tamara Payne

Ray A. Shepard

Barbara Lehman Smith

Kathleen Stone

Eric K. Washington

Sonja D. Williams

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Debby Applegate, Chair • Taylor Branch • A’Lelia Bundles • Robert Caro • Ron Chernow • Tim Duggan • John A. Farrell • Caroline Fraser • Irwin Gellman • Michael Holroyd • Peniel Joseph • Hermione Lee • David Levering Lewis • Andrew Lownie • Megan Marshall • John Matteson • Jon Meacham • Marion Meade • Candice Millard • James McGrath Morris • Andrew Morton • Arnold Rampersad • Hans Renders • Stacy Schiff • Gayfryd Steinberg • T. J. Stiles • Rachel Swarns • Will Swift • William Taubman • Claire Tomalin

|

|

|

|

|

THE BIOGRAPHER'S CRAFT

Editor

Jared Stearns

Associate Editor

Melanie R. Meadors

Consulting Editor

James McGrath Morris

Copy Editor

Margaret Moore Booker

|

|

|

|