A Writer’s Walk Spurred the Creation of BIO: An Interview with 2019 BIO Award-Winner James McGrath Morris

By Kitty Kelley

By Kitty Kelley

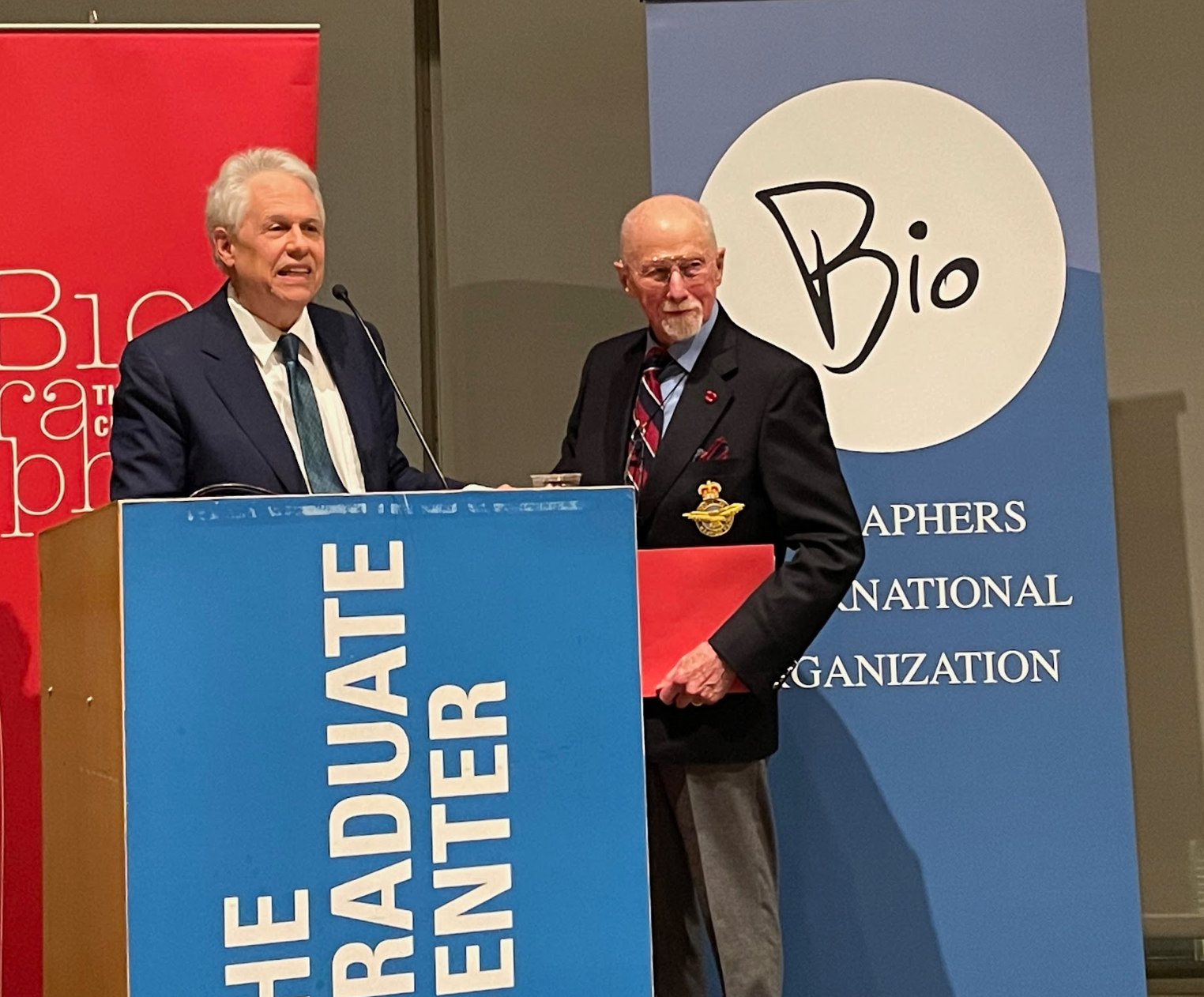

From the beginning of BIO, the organization and one person have been inextricably linked: this year’s BIO Award winner, James McGrath Morris. Even before he helped launch BIO, Morris was linking biographers through the newsletter he created, The Biographer’s Craft. He will receive his award on May 18, during the 10th Annual BIO Conference. When it came time to interview Morris, Kitty Kelley was an obvious choice. She took part in the first BIO Conference in 2010 and has known Morris since they met during a writers’ event supporting the players during the 1982 NFL strike (at least that’s Morris’s recollection). Kelley called him “my hero and beloved friend,” and let TBC know that she would have kicked and screamed if she hadn’t gotten the assignment.

Kitty Kelley: How did you come to start BIO?

James McGrath Morris: People often call me the founder of BIO, but I don’t think that’s really an accurate term because it was actually 50 of us who gathered in New York City in 2009 to found BIO. It’s more accurate to describe me as the progenitor of the idea.

KK: Where did the idea come from?

JMM: A walk. I was taking a walk on the dirt roads of my then-neighborhood, in the foothills of the Sangre de Christo mountains above Santa Fe. Walks provide time for contemplation and I was giving thought to the success of The Biographer’s Craft, a newsletter I launched in 2006. It had 1,700 subscribers who seemed to enjoy the connection to other fellow biographers that the newsletter provided.

I got to thinking that we biographers work alone but we could benefit from getting together as mystery, science fiction, romance, and thriller writers do. In fact, my friend David Morrel helped launch International Thriller Writers. So, I thought biographers needed their own organization. I wrote an open letter about this idea at the top of an issue The Biographer’s Craft that essentially said, if folks were interested in doing this, we should have a meeting. David Nasaw, who had just created the Leon Levy Center for Biography, offered space at CUNY. And 50 people showed up for the meeting.

KK: What happened then?

JMM: We decided to create an organization and, as you might imagine, we had animated discussions, especially about whether or not we would include memoirists. No, we decided.

I said that I would help facilitate the creation of this organization and stay with it until it was established, but that I did not want to stay with it forever. And there was a very important reason for that thinking. I’ve seen a lot of organizations come and go, and usually the ones that fail are the ones that are too centered on the person who helped create the organization. I felt that it would only succeed if other folks took on the responsibility of running the organization. So, I served as the executive director and then as president and then as a member of the board. Since these various tours of duty, my role has been limited to being a contributing editor to TBC and occasionally serving on a committee, like the Hazel Rowley Prize committee.

I’ve been thrilled to see that the original plan worked. If you look at the program for the conference or go to its website, you see that BIO is really a grassroots organization staffed and sustained by volunteers from all around the world. And that’s what makes BIO a healthy organization.

KK: What do you think BIO’s most important role is?

JMM: When we started BIO, we decided to hold an annual conference, and I will tell stories about this when I give my talk. I think the conference, the newsletter, the grants and prizes, and the networking BIO provides are the critically important components of its work. We have remained true to BIO’s original mission of being an organization where anyone can find help, assistance, collegiality, and support in pursuing the craft of writing a biography.

KK: What drove you to create BIO?

JMM: A bad habit. In high school, I organized Students for a Better Environment—with the catchy initials SBE—and when I worked as a freelance writer, I recruited writers for the National Writers Union. I have a drive, a tendency, or a bad habit to be a mother hen organizing folks collectively. Heck, I was even a member of the Teamsters once.

KK: How’d you first get interested in biography?

JMM: I first got interested in biography because of obituaries. I developed what some people might think is a lugubrious habit when I was very young. By that I mean, 11 or 12 years old. I loved to read obituaries in the newspaper. Not the paid announcements, although I do read those, especially in small-town newspapers, but obituaries in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Economist are

my favorites.

An obituary is a biography. It tells you the life story of somebody who is worthy of attention, but it also has to provide the context. So, it gives you a history lesson. For instance, a recent obituary for Charles Sanna, the man who invented Swiss Miss Hot Cocoa, explained how the U.S. Army ordered powdered milk during the Korean war, and how a surplus of this milk led to his invention.

From obituaries, I went to reading biographers like W. A. Swanberg and Catherine Drinker Bowen. And, of course, The Power Broker, published in 1974, made me see the incredible potential of the modern biography.

KK: Of the books you’ve written, which are you most proud of?

JMM: That question is asked to me sometimes at a bookstore event. It’s a tough question because it’s sort of like asking which of your children you like best. Each book has represented something very different in my life. I most like to write about someone that nobody else has written about. Second, I like illuminating the life of someone who is less well known, who might slip through the cracks of history. I accomplished that best with Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, The First Lady of the Black Press.

KK: What are the challenges facing biographers today?

JMM: I will elaborate on the three problems I see facing our craft when I give my talk at the conference. First, the prevalence of easily accessible biographical information about almost any figure—think Wikipedia here—has diminished the imperative of including biographies in one’s library. Because of this, the quality of the writing has become paramount. Second, it is increasingly hard to find commercial support for doing books about lesser-known subjects. Third, and conversely, it’s become a hostile world for unauthorized biographies of powerful figures. Hagiographical accounts of their lives thrive while independent and unauthorized biographies diminish. The current attacks on the press has compounded this.

KK: How do you feel about winning the BIO Award?

JMM: Obviously, I’m thrilled, touched, and honored at the same time. But it’s sort of an awkward moment. If you look at the list of previous BIO winners, which includes the likes of Claire Tomalin, Robert Caro, Ron Chernow, Stacy Schiff, Jean Strouse, and Arnold Rampersad, these are some of the most eminent biographers of our times. I’m certainly not among the rank, so it’s clear that part of the reason I was chosen is not because of some turn of phrase or some remarkably good research I did, but for my contribution in creating and launching BIO. (That’s one long sentence.) Because the prize is for somebody who’s helped advance the art and craft of biography, I can see the rationale. But, at the same time, I’m in very lofty company now, and if there’s ever a plaque made with all the winners, I’m sure somebody, when they dust it off, will say, “Oh, Robert Caro, I know him. Stacy Schiff, sure. James McGrath Morris? Who the heck was he?”

Kitty Kelley is an internationally acclaimed writer, having written seven New York Times bestselling biographies, five of which debuted at number one. Her many awards include one from the American Society of Journalists and Authors for “courageous writing on popular culture.” She serves on the BIO Board.